Kevin R. Loughlin

Boston, Massachusetts, United States

Zachary Taylor was a true Southerner born into a prominent family of plantation owners in Orange County, Virginia, on November 24, 1784, During his childhood his family moved to Louisville, Kentucky. In 1808 he obtained a commission as a first lieutenant in the army. In 1810 he married Margaret Mackall Smith, and their second daughter, Sarah Knox Taylor, would later marry Jefferson Davis, the future president of the Confederacy. For much of his life he lived on a plantation, with eighty slaves, near Baton Rouge, Louisiana.1

Taylor compiled an outstanding reputation throughout his military career. He won accolades for establishing forts along the Mississippi River during the Black Hawk War and his bravery and accomplishments during the Second Seminole War earned him the nickname “Old Rough and Ready.”

His national reputation truly emerged during the Mexican-American War starting in 1846. He led his troops to victories at the Battles of Monterrey and Buena Vista. As his fame grew, he became one of the leading contenders for the presidential nomination of the Whig Party during its convention in Philadelphia in 1848. Taylor, along with another prominent general, Winfield Scott, and two notable senators, Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, were the leading contenders on the first ballot. However, the Southern delegates rallied around Taylor and he secured the nomination on the fourth ballot. The vice-presidential nomination went to Millard Fillmore of New York, known for his moderate views on slavery. To avoid controversy, the Whigs left their convention without a platform.2 Before he ran for president, Taylor had never voted in an election.

The motive for a possible assassination attempt

Slavery was already a volatile issue during the 1848 election. Although Taylor did not publicly endorse slavery, it was assumed by many that with his Southern roots he was sympathetic to the cause. The Democratic party at its convention in Baltimore chose a platform that remained silent on slavery and nominated Lewis Cass, a U.S. Senator from Michigan, and William O. Butler, a former U.S. representative from Kentucky. However, some Democrats were ardently anti-slavery, walked out of the convention, and began the Free-Soil Party, which opposed extending slavery into the territories. They chose as their nominee former president Martin Van Buren.3 Taylor won a plurality of the popular vote in the election, defeating Cass and Van Buren. He garnered 163 electoral votes to Cass’s 127.

Soon after his election, Taylor had to face two contentious issues—an extension of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 and the Compromise of 1850. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was a federal law intended to enforce Article 4, Section 2, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution, which mandated the return of runaway slaves to their owners.4 During the 1840s, enforcement of the original law eroded and more and more slaves began to flee to the North. The intent of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was to exert harsher penalties and fines on individuals who did not return runaway slaves to their supposed owners. The suspected slave could not ask for a jury trial or testify on his or her behalf. Law enforcement officials were required to arrest people suspected of being runaway slaves on as little as a claimant’s sworn testimony of ownership.4

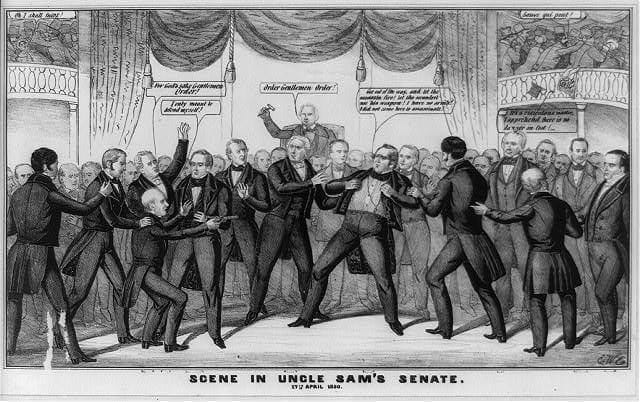

The other issue facing Taylor was whether to admit California to the Union as a free state. The Congress was divided on this issue mainly along sectional lines and vehement debate would ultimately culminate in Senator Henry S. Foote of Mississippi drawing a pistol on Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri on the Senate floor on April 17, 1850. (Figure 1) This heated controversy prompted Henry Clay to ultimately propose the Compromise of 1850, a package of five separate bills meant to diffuse the confrontation between slave and free states in the territories acquired in the Mexican-American War.5 However, despite Taylor’s Southern heritage, it became well recognized early in 1850 that he opposed the strengthening of the Fugitive Slave Law and supported the admission of California as a free state.6

It was in this setting of increasing sectional confrontation that President Taylor attended a ceremony on July 4, 1850, to lay the cornerstone for the Washington Monument. It was a typical, warm, humid summer day in Washington, exacerbated by the open sewage still present in the District. A tired, sweaty president ended the day by consuming a goodly amount of chilled milk, cold water, iced cherries, and some other fruit.

Within hours, he became ill with fever, cramps, and nausea. The physicians diagnosed cholera morbus, a general term used in that era for gastroenteritis. He was force-fed calomel (a mercury chloride solution meant to induce regurgitation), quinine (to reduce fever), and opium, none of which relieved his symptoms.7 Within four days he was moribund, and he died in the White House on July 9, 1850. Reportedly, his last words were, “I regret nothing, but am sorry that I am about to leave my friends.”

Enter Clara Rising

For over a century and a half, the conventional wisdom was that Zachary Taylor had died from gastroenteritis. Clara Rising, a retired University of Florida humanities professor, first became interested in Taylor when she stayed as a guest in his boyhood home in Louisville, Kentucky.8 As she began to read more about him, she became convinced he had been assassinated. Potential suspects were powerful men such as Henry Clay and Daniel Webster, or Southerners convinced that Taylor would veto the strengthening of the Fugitive Slave Act or other pro-slavery legislation.9 She thought it likely he was poisoned, most difficult to prove after more than a hundred and fifty years had passed. She first considered mushrooms such as amanita virosa,10 but eventually settled on arsenic being the cause. In the 1800s, this was commonly used by women to give themselves milky, white complexions, and it was also part of most golden hair dyes.11 Being odorless and tasteless, it was also the cause of accidental poisoning. In 1858 in Bradford, England, arsenic used to make lozenges was mistakenly incorporated into sweets, poisoning 200 people and killing twenty.

Zachary Taylor was not the first president suspected of having been poisoned. Historians suggested that Andrew Jackson may have died from lead and mercury poisoning from his therapeutic use of calomel (mercurous chloride) and sugar of lead (lead acetate). However, samples of Jackson’s hair failed to reveal toxic levels of either mercury or lead.12

Rising became a zealot in trying to resolve whether Taylor was poisoned. She focused on arsenic because it was easily available and because arsenic levels could be relatively easily assayed in hair and nail clippings.

Taylor was interred at the Zachary Taylor National Cemetery in Louisville, Kentucky. Rising located one of Taylor’s descendents, his great-great-great-great grandson, John McIlhenny of Louisiana, who gave permission to have the body exhumed.13 The body of Taylor was examined by George R. Nichols, the Kentucky State Chief Medical Examiner, and his team, which included Dr. Richard Greenhouse, the county coroner, and Dr. William Maples, a forensic anthropologist. Knowing that arsenic had been a common component of embalming fluid during the nineteenth century, they were prepared for possible tissue contamination from an embalming leak.14

However, the traces of arsenic they found in hair, bone, and fleshy tissues appeared to be naturally occurring and far too low to have been lethal. Dr. Nichols explained that in order to be lethal, the arsenic levels would need to have been hundreds to thousands times greater than those found.15 He concluded, “It’s not borderline, he was not poisoned.” When asked to comment, Rising concluded, “We found the truth. The truth also contains the fact that his political enemies benefitted from his removal. . . . You can still point the finger and say they got away with it even if nature did him in.”15

If not poisoning, what killed Taylor?

To delve further into the cause of Taylor’s death, one must be cognizant of the level of medical knowledge at that time. There were no antibiotics or imaging of any type. Diagnoses were based on empiric evidence, medical “hunches,” and little data other than temperature and heart rate. What is known is that after a long, humid day, Taylor consumed water, iced milk, and cherries, all of which very likely harbored bacteria.

His “gastroenteritis” very likely was due to bacterial food poisoning. The two most likely candidates are campylobacter jejuni or salmonella. Campylobacter jejuni still infects about 1.5 million Americans each year. It is found in many farm animals, raw foods, or milk. Symptoms can begin within hours after ingestion and typically last about seven days. The symptoms include nausea, cramping, diarrhea, and fever.16

The Centers for Disease Control estimates that salmonella still causes 1.35 million infections, 26,500 hospitalizations, and 400 deaths each year in the United States.17 The clinical symptoms of diarrhea, abdominal cramps, headache, nausea, and vomiting usually start within hours of infection. Raw poultry, eggs, and unwashed fruits or vegetables are the most likely sources of salmonella infection, which was first described by Dr. Daniel E. Salmon in 1885.18

The onset of Taylor’s symptoms and death fit the pattern of either infection. The raw, unwashed food and drink he consumed are the likely culprits. With the hindsight of one hundred seventy years, it is reasonable to conclude that Taylor was not assassinated by a cabal of disgruntled Southerners, but rather that his death was most likely due to a “bad bowl of cherries.”

References

- Zachary Taylor-History. https://www.history.com/topics/us-presidents/zachary-taylor

- United States presidential election of 1848. https://www.britannica.com/event/United-States-presidential-election-of-1848

- 1848 United States presidential election. https:www.wikipedia.org

- Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. https://www.wikipedia.org

- Compromise of 1850-Summary, Significance and Facts. www.history.com/topics/abolitionist-movement/compromise-of-1850

- Hagen,C. From the Ashes: The Dewey Annals: Volume Two. https://smart-answers.com/history/question

- Crockett, Z. How Did President Zachary Taylor Actually Die? Priceonomics 7/2/2015. https://pricenomics.com/how-did-president-zachary-taylor-actually-die

- McLeod, M. Cara Rising, Ex-UF Prof Who Got Zachary Taylor Exhumed, Orland Sentinel 7/25/92

- Marriott, M. President Zachary Taylor’s Body To Be Tested For Signs Of Arsenic. NY Times 6/15/91 Section 1, page 1

- Rising C. The Taylor File, Xlibris, Corporation, 2007

- Walton, G. Arsenic in the 1800s: A Dangerous Poison. https://www.geriwalton.com/arsenic-in-the-1800s-a-dangerous-poison/

- Deppisch LM, Centeno JA, Gemmel DJ, Torres NL. Andrew Jackson’s Exposure to Mercury and Lead: Poisoned President? JAMA 1999; 282(6):569-571

- Marriott, M. Op. cit.9

- Marriott, M. Zachary Taylor’s Remains Are Removed For Tests. NY Times. 6/18/91, section A, pg.10

- Marriott, M. Verdict In: 12th President Was Not Assassinated. NY Times 6/27/91, Section A, pg.14

- CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cedc.gov/campylobacter

- CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/index.html

- https://www.www.cdc.gov/salmonella/general/index/html.

KEVIN R. LOUGHLIN, MD, MBA, is a retired urologic surgeon and professor emeritus at Harvard Medical School. He has a longstanding interest in presidential health.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 1 – Winter 2021