Edward McSweegan

Kinston, Rhode Island, United States

|

| Doctor Mary West Niles, Wikipedia |

Bubonic plague arrived in Honolulu in December 1899. A month later it had spread to San Francisco, where the infection caused a series of deadly outbreaks until 1907.1 But for decades before plague reached the American west coast, it had burned through rural China. By 1893, the plague reached Canton (now Guangzhou), where it caught the attention of Chinese officials and British colonials. It also caught the attention of Mary W. Niles, M.D.

Niles was the first American female physician to practice medicine in China.2 She was born in Wisconsin in 1854 and graduated from New York’s Elmira College in 1875. Niles then spent three years teaching and doing missionary work in New York City before entering medical school. She graduated from the NYC Women’s Medical College in 1882 and headed off to China as a missionary doctor.

Under the auspices of the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions, Dr. Niles taught and practiced gynecology and obstetrics at the Canton Hospital. In addition to routine surgeries and patient visits, she found time to learn Cantonese and later started a school for blind Chinese girls. Remarkably, she also translated the Braille writing system into Chinese characters for her students at the Mingxin School for the Blind and translated two medical textbooks for Chinese doctors.3

|

| Hong Kong Inspectors, 1894, Wellcome Collection. (CC BY 4.0) |

Niles saw her first case of bubonic plague on January 16, 1894, and reported that case and seven others to local authorities. Niles wrote, “It has been noticeable to the people that rats in infected houses have died.”4 Rats, dead and alive, were everywhere, and Niles suggested the rats were “the major transportation means for the spread of disease and . . . a missing link in the chain of plague transmission.”4 Canton officials responded to her idea of a rat-disease linkage by offering money for dead rats and instituting clean street policies to reduce food sources for Canton’s ubiquitous rats.

The rats, particularly the dead ones, offered an important clue about the disease. The etiological agent of bubonic plague was still unknown, as was the means of transmission from person to person. Dr. Niles continued to treat plague patients, wondering “how the [plague] poison enters the system.”5 As the number of dead increased, residents who could leave by road or boat did so. “From Canton, which communicates with so many places, the infection was bound to be disseminated,” wrote Niles.4

When plague spread into nearby Hong Kong in May 1894, the French Colonial Health Service sent Alexandre Yersin to investigate the outbreak.1 Yersin isolated the bacterial agent, later named Yersinia pestis, from the buboes of plague victims. The Japanese bacteriologist Kitasato Shibasaburō was also in Hong Kong in 1894 and simultaneously identified the same bacterium as Yersin. Mary Niles noted the presence of “Professor Kitasato” in Hong Kong.5

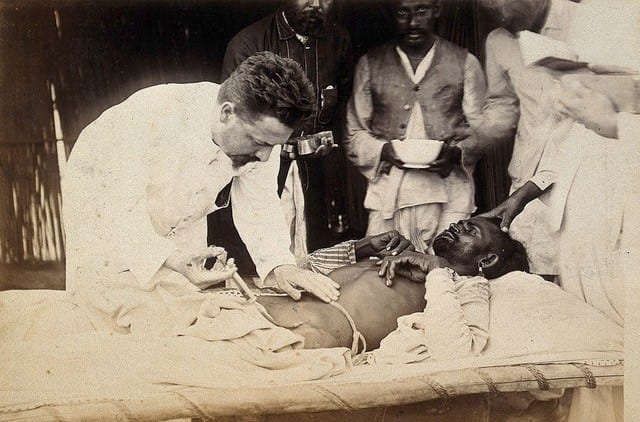

|

| Simond in Karachi, 1897. Credit: Wellcome Collection. (CC BY 4.0) |

Niles also observed that rats living in the ground and in drains were the first animals to fall victim to the plague. But both the Chinese and the local Europeans thought rats caught the plague from humans. Three years later, Japanese physician Masanori Ogata sought to change the focus on rats when he wrote, “One should pay attention to insects like fleas for, as the rat becomes cold after death, they leave their host and may transmit the plague virus directly to man.”6 At least one French doctor paid attention.

In 1897, Paul-Louis Simond was in India studying plague. Examining fleas from rats killed by plague, he found they were full of Yersin’s bacilli. In Jurrachee (now Karachi, Pakistan) the following year, Simond carried out a series of clever experiments demonstrating how bacilli-infected fleas could infect and kill a rat and then pass through a screen mesh to infect and kill a second rat. (Two years later, in Cuba, Walter Reed would use a similar screen separation technique to show how only mosquitoes could transmit yellow fever to human volunteers.) Simond wrote, “That day, 2 June 1898, I felt an emotion that was inexpressible in the face of the thought that I had uncovered a secret that had tortured man since the appearance of plague in the world.”7

But the world would not be convinced fully until 1906. In the interval, bubonic plague spread through China and India and then gained a foothold in California. In an article about the Canton plague, Mary Niles wrote, “In the fourteenth century the plague is said to have been spread through Europe and Asia from China. It is to be hoped that we shall not again become the distributing center for the world.”5 Unfortunately, this third plague pandemic spread out from China to land on five continents.8

Dr. Niles retired in 1928 after almost a half-century of extraordinary work in China. In California, the seventy-eight-year-old Niles died of pneumonia in 1933.9 She had educated hundreds of blind girls; introduced hundreds of female patients to modern medicine; and inspired a growing cadre of Chinese women doctors.

References

- Randall DK. Black Death at the Golden Gate. The race to save America from the bubonic plague. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co. 2019.

- Livingston, RS. Women in Medicine: Past, Present, & Future. 2015.

- Xu G. American Doctors in Canton: Modernization in China, 1835-1935. New York, NY: Routledge. 2017.

- Simpson, WJ. Report on the Causes and Continuance of Plague in Hong Kong and Suggestions as to Remedial Measures. Waterlow and Sons Printers, London, U.K. 1903. Available at: https://bit.ly/3boX2i4. Accessed April 17, 2020.

- Niles, MW. “Bubonic Plague in Canton.” NY Med. J. Oct. 13, 1894, pp. 467-468. Available at: https://bit.ly/3cxgUQq. Accessed: April 18, 2020.

- PBS. “Bubonic plague hits San Francisco, 1900-1909.” Available at: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aso/databank/entries/dm00bu.html. Accessed: April 17, 2020.

- Simond M., Godly ML., Mouriquand PDE. Paul-Louis Simond and his discovery of plague transmission by rat fleas: a centenary. J. Royal Soc. Med. 1998;91:101-104.

- Frith J. The History of Plague – Part1. The Three Great Pandemics. J. Mil. Veterans Health. 2012;20(2):11-16.

- “Dr. Mary W. Niles,” The New York Times, January 22, 1933, Page 25.

EDWARD MCSWEEGAN, Ph.D., is a microbiologist in Rhode Island. He worked at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and later at the Global Virus Network in Baltimore. He writes about infectious diseases and history.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 1 – Winter 2021

Spring 2020 | Sections | Women in Medicine

Leave a Reply