Jack Riggs

Morgantown, West Virginia, United States

All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players. They have their exits and their entrances, and one man in his time plays many parts.

– William Shakespeare

Public domain.

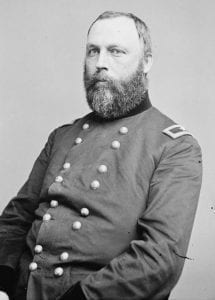

Shakespeare’s words describe the extraordinary life of William Alexander Hammond.1-8 LC McHenry, a historian of neurology, dubbed Hammond “one of the first and certainly the most colorful of American neurologists.”9 Hammond exerted a profound influence on American neurology during the second half of the nineteenth century. Among his accomplishments,1-8 Hammond wrote the first American text on neurological disease (A Treatise on the Diseases of the Nervous System), helped start the first American neurological journal (Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease), established one of the first and most successful practices limited to neurological disease in the United States, coined the term “athetosis,” and was the driving force in the formation of the American Neurological Association.5,10 Hammond’s impressive list of neurological accomplishments in the 1870s could hardly have been predicted by his activities between graduation from medical school in 1848 and national humiliation in 1864.5

Hammond was commissioned in the U.S. Army as an assistant surgeon in 1849.5 He served in the army until 1860 at isolated posts in New Mexico, Florida, Kansas, and Michigan.5 Despite intellectual isolation, Hammond developed an academic interest in physiology.5 He published his first article on the use of potash in the treatment of scurvy in 1853,12 and in 1857 went on to win first prize in a national American Medical Association research competition.5 As a result of his achieving a degree of national recognition for his academic pursuits while serving as an army medical officer, Hammond was offered a professorship in physiology at the University of Maryland in 1860.5

When the Civil War broke out, Hammond quickly left academia and returned to the army.5 Because of his break in service, he lost all rank and seniority. As the U.S. Army rapidly expanded from 15,000 to over one million personnel at the beginning of the Civil War, medical capacity in the army was virtually nonexistent. Hammond, however, quickly demonstrated a remarkable ability to organize that far exceeded his peers. Under his direction, new military hospitals were built in Wheeling, Parkersburg, and Grafton, Virginia (now West Virginia). After wounded Union soldiers were left unattended for days on the Bull Run battlefield, a loud civilian outcry for reorganization of the Army Medical Department occurred.

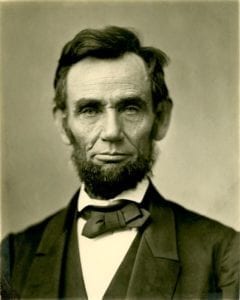

Reverend Bellows, president of the Sanitary Commission, pleaded directly to President Lincoln to name Hammond Surgeon General.13 As the President signed a stack of papers, Bellows made an impassioned and prolonged plea. After Bellows was finished making his request, Lincoln looked up and jokingly said,

Shouldn’t wonder if Hammond was at this moment Surgeon General, and had been for some time.13

Lincoln had already signed the paperwork making Hammond Surgeon General while Bellows was pleading his case. At the age of thirty-four, Hammond became U.S. Army Surgeon General on April 17, 1862. President Lincoln also issued Bellows a warning concerning Hammond that proved prophetic,

Stanton’s one of my team and they must pull together, I can’t have any one of ‘em a-kicking out.14

Lincoln had named Edwin M. Stanton Secretary of War in January 1862. Lincoln had been pressing for a more aggressive prosecution of the war and was indicating to Bellows his strong support of Stanton, who would be Hammond’s immediate superior. Lincoln was also indicating that Hammond needed to get along with Stanton, not vice versa. Indeed, Lincoln had named Hammond Surgeon General against the wishes of Stanton. Stanton was quoted as saying,

[T]he fact is the Commission wanted Hammond to be Surgeon-General and I did not. I did my best with the President and with the Military Commission of the Senate, but the Commission beat me and got Hammond appointed. I’m not used to being beaten, and don’t like it.13

The initial meeting between the new Surgeon General Hammond and Secretary of War Stanton has been preserved in Hammond’s own words,

I went to his office and the following conversation took place. His tone and manner were offensive in the extreme. He began with a question as to the Sanitary Commission and continued, “I want to tell you that if you have the enterprise, intelligence, and brains to run the Medical Department I will assist you.” “Mr. Secretary,” replied Hammond, “I am not accustomed to be spoken to in that manner by any person, and I beg that you will address me in more respectful terms.” “What do you mean?” he exclaimed. Hammond replied, “I was accustomed in the Army, even with low rank, to be addressed in a respectful manner, and as Surgeon General will certainly permit no less.” “Then, Sir, you can leave my office immediately.” said Stanton.15

Hammond had not appreciated Lincoln’s warning about working with Stanton. Nevertheless, Hammond successfully revamped the U.S. Army Medical Department and instituted changes in military medicine that continued into the twentieth century. He also created the precursors of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology and the National Library of Medicine.5 In less than eighteen months, however, Hammond’s control over military medical matters was removed by Stanton.

In the fall of 1862, Hammond transferred J.T. Murray, a military surgeon, to Philadelphia to replace George Cooper.4-5,8,14-15 Surgeon Cooper was transferred to the Army of the Cumberland. After Cooper was injured, he made complaints to Secretary Stanton about the circumstances of his transfer and perceived irregularities in purchases made by the Army Medical Department. Stanton saw his opportunity to move against Hammond and convened a Civilian Commission of Inquiry to investigate the allegations. Former Kansas Governor Andrew Reeder, an avowed enemy of Hammond, was appointed by Stanton to head the investigation. In December 1863, Stanton sent a report on the charges and specifications against Hammond to Judge Advocate General Holt. Holt found sufficient evidence against Hammond to justify summary dismissal, but recommended a court martial. On December 26, 1863, Lincoln responded to Holt’s recommendation by writing,

Let the Surgeon General be put upon trial by a Court, as suggested by the Judge Advocate General.14

Abraham Lincoln had interfered once with his Secretary of War over Hammond, he would not do so a second time. The court martial began on January 30, 1864 and concluded with Hammond’s conviction on May 7, 1864. Lincoln, after having the 2500 pages of evidence and testimony reviewed, affirmed the findings of the court martial on August 18, 1864. Hammond was dismissed as Surgeon General.14

Following his conviction, Hammond began a fifteen-year struggle to clear his name. In an open letter to the Senate of the United States dated December 25, 1864 and published in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, Hammond complained that,

[T]he finding and sentence of the Court to be illegal, and not warranted by the facts of the case; that they were procured by conspiracy and false testimony, and that consequently his removal from office, and the disability placed upon him, are unjust and wrongful.16

Hammond felt personally betrayed by Lincoln. In a revealing editorial published shortly after the assassination of Lincoln, Hammond wrote,

If, during his administration, acts were done in his name not in themselves right; if others were omitted which should have been performed; if wrongs were inflicted upon individuals for which full amendment can never be made, the responsibility cannot with justice be fastened upon him. It rests with those who were appointed to advise and assist him in the multitudinous duties of his great office, and in whom he trusted with the child-like confidence which formed so prominent a feature of his open and ingenuous disposition.17

While superficially praising Lincoln, Hammond faulted Lincoln’s “child-like confidence” in those he appointed. Eventually, on August 27, 1879, President Hayes reversed the sentence and restored Hammond to the rank of Brigadier General (retired).5

Hammond died suddenly at his home on January 5, 1900 at the age of seventy-one. An obituary notice, published in the Medical Record on January 13, 1900, concluded with the following comment,

Dr. Hammond was a man of undoubted ability, but his methods were not always in conformity with the unwritten code of professional ethics.18

A more fitting legacy for Hammond, however, is his recognition as one of the founding fathers of American neurology.1-11 Hammond’s life took many unexpected turns. Abraham Lincoln brought William Hammond into the national spotlight and the turbulent and often unforgiving arena of national politics. As a result of Lincoln’s dismissal of Hammond as U.S. Army Surgeon General, Hammond’s organizational skills and abilities were refocused from military medicine to the emerging field of neurology. Thus, the actual emergence of American neurology can be viewed to some degree as the unintended consequence of the actions of President Lincoln in appointing and removing William Alexander Hammond as U.S. Army Surgeon General during the Civil War. This historical vignette should not be interpreted as suggesting that without Hammond or Lincoln, American neurology would not have emerged. Rather, the actual manner in which American neurology did emerge was a reflection of the interaction between Hammond and Lincoln.

Washington politics is often characterized by the clash of great egos with extraordinary abilities. The fallout of these clashes can often be ruinous to individuals. However, flexible individuals like Hammond can express their innate talent in different arenas when their original focus is thwarted by Washington politics. The actual course of American neurology was influenced by a classic Washington political power struggle.

References

- Drayton ES. William Alexander Hammond, 1828-1900, Founder of the Army Medical Museum. Mil Surg 1951;109:559-565.

- McHenry LC. Surgeon General William Alexander Hammond. Mil Med 1963;128:1199-201.

- Schoenburg DG, Schoenberg BS. William Alexander Hammond: notorious neurologist of note. South Med J 1979;72:346-7.

- Klawans HL. The Court-Martial of William A. Hammond.In: The medicine of history, from Paracelsus to Freud. New York: Raven Press; 1982.

- Blustein BE. Preserve your love of science, life of William A. Hammond, American neurologist. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1991.

- Freemon FR. The first career of William Alexander Hammond. J Hist Neurosci 1996;5:282-7.

- Freemon FR. William Alexander Hammond: the centenary of his death. J Hist Neurosci 2001;10:293-9.

- Freemon FR. Gangrene and glory, medical care during the American Civil War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press; 2001.

- McHenry LC. Garrison’s History of Neurology. Springfield: Charles C. Thomas, 1969.

- Stookey S. Historical background of the Neurological Institute and the neurological societies. Bull NY Acad Med 1959;35:707-29.

- Blustein BE. New York neurologists and the specialization of American medicine. Bull Hist Med1979;53:170-83.

- Hammond WA. Observations on the use of potash in the treatment of scurvy; with cases. Amer J Med Sci 1853;25:102-105.

- Maxwell WQ. Lincoln’s fifth wheel, the political history of the United States Sanitary Commission. New York: Longmans, Green & Co., 1956.

- Friend HC. Abraham Lincoln and the court martial of Surgeon General William A. Hammond. Commercial Law 1957;62:71-8,80.

- Duncan LC. The strange case of Surgeon General Hammond. Mil Surg 1929;64:98-110,252-62.

- Hammond WA. To the Honorable, the Senate of the United States. Boston Med Surg J 1865;71:527-528.

- Hammond WA. Abraham Lincoln (editorial). NY Med J 1865;1:163-4.

- Obituary. Dr. William Alexander Hammond. Med Rec 1900;57:64.

JACK E. RIGGS is a Professor of Neurology at West Virginia University. He spent 29 years in the Navy Reserve, retiring as a Navy captain.

Leave a Reply