Falk Steins

Niedernhausen, Germany

Stephen Martin

Baan Dong Bang, Thailand

The oil painting Portrait of a Lady Holding an Orange Blossom (Fig. 1) was acquired by the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2020. Newly discovered documents supporting the lady’s almost certain identity tell a remarkable story of the late Dutch Republic.

The painting shows a young woman wearing an elegant blue silk dress edged with lace and a bonnet. The expensive fashion was typical of the early 1770s Netherlands. Her lavish jewelry consists of a double pearl necklace, two double pearl bracelets, a pair of jewel-set, cut-steel earrings, and a similar brooch on her bonnet. It all reflects the influence of the East India trade.

In her right hand she holds a twig with leaves, buds, and flowers from the orange tree1 behind her. Native to Southeast Asia, it had been prized in Europe since the sixteenth century as an ornamental plant and status symbol. The fruit and flower became emblems of the Orange-Nassau political dynasty, as well as representing love, beauty, mortality, and rebirth. Here, purity and innocence also come across. She is in a small, walled formal garden, with a Masonic-looking fountain-obelisk, circular ground pool, and square flower bed.

Her face has the slightness of late adolescence, not having finished growing. It seems safe to say that she is almost certainly fully Javan, corroborated with confidence by the authors’ friends and colleagues from Indonesia.

Close examination revealed the artist’s signature “J. Schul… fec” obscured by layers of varnish.2 Comparison with other works identified the artist as Jeremias Schultz, born in Berlin in 1723. In the 1740s, he moved to Amsterdam with his older brother to paint professionally.3

From 1750 to 1781, Schultz portrayed mainly residents of Amsterdam and nearby cities. Only a few of his works are in museums, but another interesting one sold at Christie’s, New York in 2011. Generally regarded as a companion piece to the “Orange Blossom Lady,” it too was painted in the early 1770s, showing another apparent Javan.4 The clothes are a green suit of jacket, waistcoat, and juste-au-corps, and a silk shirt with neckcloth and gold-braided cane. It has been suggested that this may be a relative or spouse.5 We suggest a different, disarmingly simple solution: the two paintings show the same young woman at different maturity, from the hip-shoulder ratio and many identical facial features, including sinus ridges, forehead shape, hair, nose cartilage, eyebrow curves and nostril curves. Who was she, and why was she painted in this fashion?

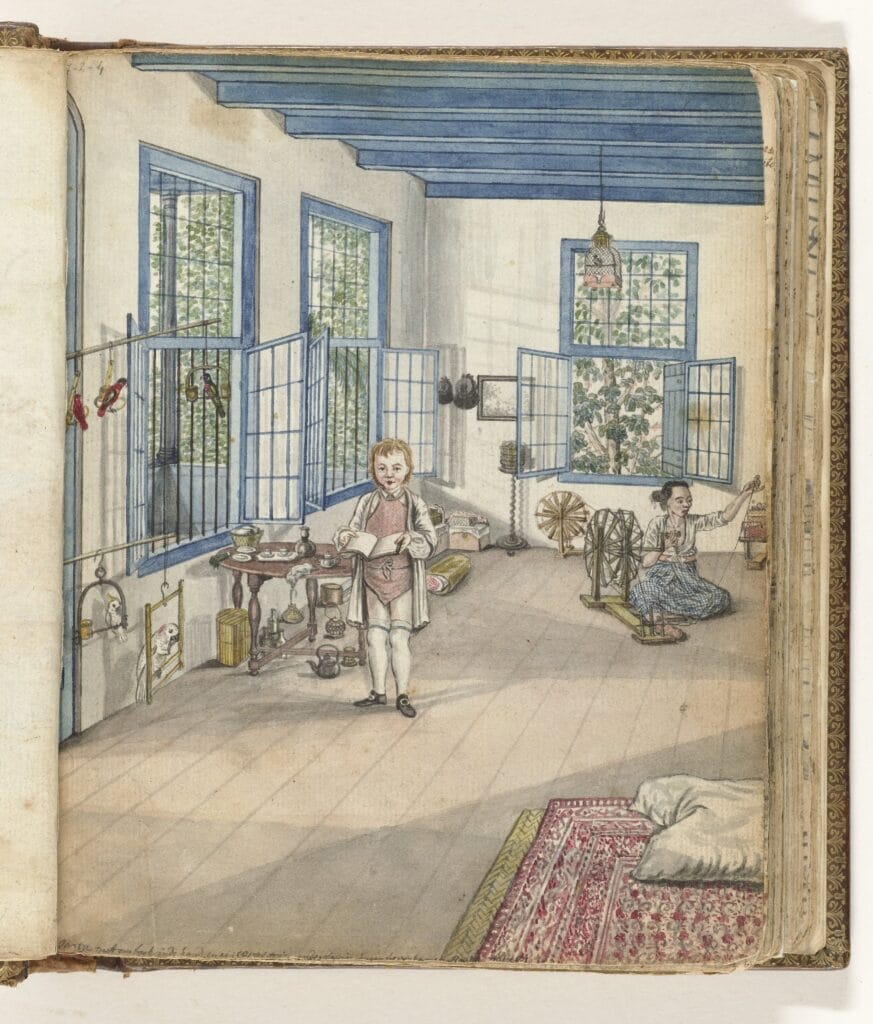

Dr. Ferdinand Dejean,6 who sponsored fellow Freemason Mozart’s flute works,7 was born in Bonn in 1731. He became a ship’s surgeon in the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in 1758 and went to Asia, working in that position for several years. In June 1762, he was appointed city surgeon of Batavia, capital city of the VOC, today’s Jakarta, settling on the prestigious main avenue, the Tijgersgracht.8 There, he described his large house with around twenty slaves.9 One was a young girl, later recorded as Anna (Maria) van Java.10 Slaves made up a substantial part of Batavia’s population and were considered an important luxury. Some did public service like construction work, while the slaves in personal ownership were mostly craftsmen or domestic servants skilled in cooking, playing an instrument, embroidery, or lacemaking. (Fig. 2) Many female slaves became concubines or victims of sexual abuse by their masters.11

In 1767, Dejean decided to leave Batavia for Europe and take his pregnant wife, Anna Maria Pack, along with his one-year-old stepson Jacobus Wilhelmus. Anna was the widow of the merchant Wilhelmus Buschman. Their servant girl went along, for whom he needed the consent of the authorities and had to pay for transport and boarding.12 It stands to reason she was needed to look after the pregnant Anna and her son. Dejean’s son, George Ferdinand, was born aboard the ship Ouderamstel in May 1768, almost one month before the ship’s arrival at the island of Texel.

Dejean, who was now financially independent,13 settled with his family in Amsterdam and rented rooms in the university town of Leiden.14 There, he began studying medicine and philosophia naturalis—natural sciences—concluding both with dissertations published in 1773. In the latter, Dejean revealed his surprising view: “Slavery in itself is not unjust, or contrary to the precepts of Christian ethics, but its extension to posterity [its hereditary nature] may be unjust or unfair.”15 Slavery had been made illegal in Britain the previous year.

Asia traded less VOC slaves than Africa, but could be just as cruel and despotic.16 In the Netherlands, slavery was officially long-abolished. The “free-soil principle” dictated that arriving slaves were automatically freed. In 1776, however, the Dutch state confusingly decreed: “… the aforementioned truth [abolition of slavery] cannot in all respects be applied to negro and other slaves, who are brought over from the colonies … or sent here.” Additionally, anyone who traveled to the Netherlands with the knowledge or at the request of the owner and remained there would be freed.17 Even if Dejean had not officially freed Anna before the sea voyage, upon her arrival she ceased being a “possession.” Anna received Christian baptism, endorsing her personal freedom. There is no reason to doubt that she was relatively well provided for, as well as received some education.

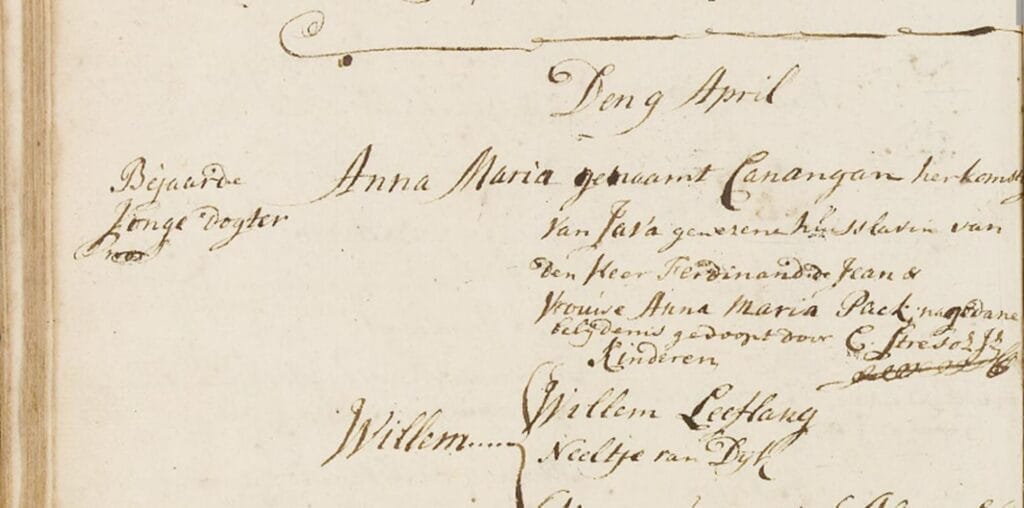

We surmise that the orange blossom painting marked Anna’s christening on the April 9, 1772, in the Dutch Reformed Hooglandse Kerk at Leyden. Her baptismal entry (Fig. 3) reads: “Anna Maria named Canangan from Java, former house slave of Master Ferdinand de Jean and his wife Anna Maria Pack; having delivered her profession of faith baptized by C. Stresos Jz.” In the margin she is called “older young daughter” (“bejaarde jonge dogter”), distinguishing her christening from that of a child.18 From seven years of exhaustive searches, Anna is the only Southeast Asian of the time in Holland with both personally documented events and proven background fitting the context of the portrait.

The name “Canangan” in the parish register is intriguing, being both a given and place name.19 The Cananga tree (Cananga odorata) has one of the most fragrant and beautiful flowers of Indonesia, the Ylang-Ylang, source of the oil, making a likely choice for a native Javan girl.20

Among the aspects that make the painting special are the attributes of a wealthy lifestyle and self-assurance, unique for former VOC slaves. Case studies demonstrate that, left to their own devices, they were often confronted with poverty, at best finding themselves in military or artisan occupations, or serving wealthy households for show.

The Dejeans did not consider Anna/Canangan in their first will, which they jointly set up in 1768. However, Dejean made generous provision for her in 1775 after the deaths of his wife and stepson.21 He bequeathed “a certain Anna from Java, who came with him from the East Indies … as a token of satisfaction for her services rendered to him and his deceased housewife an annual sum of thirty guilders, starting from his decease, lasting her whole life, or instead on his decease a sum of two thousand guilders, which will be lent at her choice.”

But something must have happened that changed Dejean’s attitude completely. In a dramatic codicil to his will of 1780, he revoked the bequest “because by her conduct, as a result of which he had considerable expenses, she has proved herself utterly unworthy.”22

In 1780, Dejean left the Netherlands and settled with his sister’s family at Rheinberg, Electorate of Cologne, before moving to Vienna in 1790, where he died seven years later. Anna was left behind to take care of herself. There is no more news of her until her burial on May 1, 1808, in Amsterdam. She was still called “Anna Maria Java,” apparently never having married.23

Was she content to lead a better life than she could have hoped for as a slave in her native country? Although freed slaves rarely transcended a life of subjection and poverty, we will never really know. Former slaves did not usually write their own stories.

There is a very high probability that the Orange Blossom Lady is Anna/Canangan van Java. The portrait’s unique opulence in a Southeast Asian woman, the fit to Dejean of a rare combination of symbols in the late Dutch Republic, and a good explanation uniquely documented for the time with no other candidate having similar evidence within a small group, raise her identity from a remote possibility to an almost certain one. Fresh sources like personal papers of Dejean or Schultz’s client register would help; unlikely, but not impossible.

Was it a bad life, and a sad life for Anna? She certainly had a major transition with cultural dislocation, the potentially depressing deficit of loneliness, and homesickness. Even in the urban environment of Amsterdam, it must have been stressful for a Javan woman to blend in with the Dutch society of the 1770s with a new climate, language, social conventions, and morals of a firmly Protestant society to respect, and well before a significant diaspora of native Indonesians arose. Everyday ostracism and racism were to be expected. Also, she had to deal with bereavements of young Jacobus Buschman and her mistress Anna Maria Dejean. George Dejean, whom she had nursed since his birth, was taken out of her hands right after the death of his mother.24 Anna’s final unique aspect is a completely documented set of defined, modern interpersonal stresses, namely role transition, bereavement, and interpersonal deficit, culminating in her last parameter, the role dispute of her disinheritance.

Anna’s apparent portrait and exceptional documentation of her experiences in transition to freedom both paint unique and consistent pictures.

End notes

- Deborah Metzger. Portrait of a Lady with Orange Blossom – The Orange Blossom in https://ago.ca/collection/portrait-of-a-lady-holding-an-orange-blossom states: “the blossom is either Citrus aurantium, the bitter orange or Citrus sinensis, the sweet orange.”

- Art Gallery of Ontario. A Portrait of Possibilities – The Painting as a Physical Object in https://ago.ca/collection/portrait-of-a-lady-holding-an-orange-blossom

- Schultz was christened in St. Nikolai church on October 11th, son of shoemaker Christoph Schultz and Elisabeth Schultz. On February 7th, 1751 at Amsterdam, he married Anna Helena, daughter of the famous painter Herman van der Mijn. After the death of his first wife in July 1759, he immediately married Jacoba Catharina Smit, daughter of tapestry painter Johannes Smit. Schultz died in Amsterdam in 1800, buried October 13th, leaving behind three daughters.

- https://www.christies.com/lot/lot-j-schult-german-18th-century-portrait-5453455/ Accessed May 2025. We apologize to Hektoen readers that despite assiduous efforts, we were unable to obtain workable permission to reproduce this image.

- Sarah Murden. Blog: “All things Georgian,” 2020. https://georgianera.wordpress.com/2020/09/02/portrait-of-a-lady-holding-an-orange-blossom. The Orange Blossom Girl has an uninterpreted collection number 52 painted on the front in a cartouche. The Green Suit painting has no such number. Women’s dress emulating men’s clothing was not uncommon throughout Anna’s time. Anna Amalia von Preussen had a silver “Amazon” dress (in GK 1028, Charlottenburg Palace), and British Regency women emulated Court robes in their dresses. A mysterious portrait, reputedly of Cootje de la Sablonière (private collection), also by Jeremias Schultz in Holland, again looks very feminine in facial shape and shoulder-hip ratio, being remarkably similar in dress to the companion piece. https://kampenonline.nl/stadswandeling-op-stap-met-de-familie-de-la-sabloniere/ A detailed image of the Green Suit portrait is still available on Christie’s website.

- Stephen Martin. The symbolic portrait of Mozart’s patron Dr Ferdinand Dejean. Hektoen International, Spring 2018. https://hekint.org/2018/04/12/symbolic-portrait-mozarts-patron-dr-ferdinand-dejean

- Stephen Martin. The patronage and playability of Mozart’s flute works. Hektoen International, Fall 2021. https://hekint.org/2021/10/21/the-patronage-and-playability-of-mozarts-flute-works

- Falk Steins. https://ferdinanddejean.jimdofree.com/english A detailed background, chronology, and Dejean biography. Few survived the East Indies to return to Europe. Dejean was extraordinarily wealthy for a doctor and although he accepted slavery, he was certainly a well-read moral philosopher, fitting his philanthropy to Anna Canangan.

- Jürgen G. Nagel. Zwischen Kommerzialisierung und Autarkie – Sklavereisysteme des maritimen Südostasiens im Zeitalter der Ostindienkompanien, Comparativ, 13, 2003, p. 43. Slavery was part of everyday life in Southeast Asia and had been adopted without hesitation by the Dutch. How they were treated ranged from respected staff to abject victims. They were not referred to as bediende, the Dutch for servant, which was in use in the Netherlands at the time.

- Reggie Baay. Daar werd wat gruwelijks verricht: slavernij in Nederlands-Indië, Amsterdam, 2015, p. 123. Slaves were depersonalized by their owners by being given a European first name, usually followed by a toponym reflecting their geographical origin instead of their original names. It was also common practice to give the former slaves the first name(s) of the godparent on the occasion of their Christian baptism, as was probably the case here. There were no Javan surnames at the time.

- Sometimes they were also exploited in forced prostitution, see: Baay, op. cit., p. 126-132. The law required female slaves to be freed, however, if they were made pregnant by their masters (ibid., p. 149), which could be a mixed blessing as the European man could free himself of economical responsibilities for the Asian woman and child if he wanted to. The large number of relationships between European men and Asian women was promoted by the continual scarcity of European women in the East (ibid., p. 265). If a European wanted to marry one of his slaves, the prospective groom was obliged to purchase his bride’s freedom and have her baptized with a Christian name, cf. Taylor, Jean Gelman, The social world of Batavia, 2nd ed., Madison/Wisconsin 2009, p. 16. From 1639 on, no man married to an Asian woman might repatriate (alone) while his wife and their children still lived (ibid., p. 29).

- Matthias van Rossum. Kleurrijke tragiek: de geschiedenis van slavernij in Azië onder de VOC (= Zeven Provinciën reeks 35), Hilversum 2015, p. 78-9. Originally, enslaved servants were to be sent back to their respective colonies after arriving in the Republic, but many VOC officials ignored this order, cf. Holzmann, Julia, Geschichte der Sklaverei in der Niederländischen Republik. Recht, Rassismus und die Handlungsmacht Schwarzer Menschen und People of Color 1680-1863, Bielefeld 2022, p. 18.

- Martin, Stephen. Was the VOC Funding Mozart? The Diaries of Wilhelm Buschman on Kharg Island. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 33, no. 2, 2023: pp. 489–511. It was wealth both from his own business affairs and especially from the substantial capital his wife brought into the marriage from her first husband’s pearl embezzlement.

- From the surgeon Cornelis Schilham. See: Otto Bleker, Frank Lequin. Ferdinand Dejean 1731-1797. VOC-chirurgijn, wereldburger en opdrachtgever van Mozart. Wormerveer, 2013, p. 289. In all likelihood it was on a Leiden street called Hogewoerd, the oldest part of which near the city center typically had five-meter-wide courtyards behind the houses, as did many houses on Herengracht in Amsterdam, where the family lived. So, if the painting’s background was real and not an imaginary landscape, it might well have been Dejean’s garden.

- Ferdinand Dejean. Historia, analysis chemica, origo, et usus oeconomicus sodae hispanicae. Dissertatio inauguralis chemica-oeconomico.practica, Leiden 1773, Thesis III, last but one page of the unpaginated volume, translation from Latin, online here: https://books.google.be/books?id=8QlTAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=de&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Baay, op. cit., pp. 101-147, and van Rossum, op. cit., passim. In East Asia, slavery was not only an accepted fact, but also an important economic factor for the VOC. In “Nederlandsch-Indië” slavery was not abolished before 1860, and even afterwards the law took a long time to implement, see: van Rossum, op.cit., p. 7, and Baay, op. cit., p. 202. General abolition of slavery in all Dutch territories came late, in 1863.

- Plakaat, concerneerde de vryheid der Slaaven, May 23rd, 1776, cf. Holzmann, op. cit., pp. 126-131.

- Erfgoed Leiden en omstreken te Leiden, DTB Leiden, Dopen, deel 253, archief 1004, inventarisnummer 253. https://www.openarchieven.nl/elo:3867f12d-f827-584e-717e-275f20f119cd/nl Dutch text: “Anna Maria genaamt Canangan herkomst van Java gewesene Huissklavin van de Heer Ferdinand de Jean & Vrouwe Anna Maria Pack; na gedane belydenis gedoopt door C. Stresos Jz.”

- If the latter meaning is intended, there are two villages by the name of “Kananga” on Java, one in the west in the province of Banten, one further to the east in Jawa Bara. The place names “Canangan” and “Kananga” also exist in the Philippines, which may be relevant since especially the inhabitants of the Sulu archipelago were active slave traders, cf. Nagel, op. cit., p. 54. However, the VOC had not only banned Javanese people from living in the city of Batavia, but also prohibited their use as slaves there—it was considered advisable to have a slave population as mixed in origin, language, customs etc. as possible to prevent insurrections, cf. Haan, Frederik de, Oud Batavia 1, Batavia 1922, p. 452, and Taylor, op.cit., p. 18. So, either Anna/Canangan’s origin lay elsewhere and she was only called “van Java” in the Netherlands, or the law had been watered down by that time.

- Considering the preference for flower names in many languages, vouched for in Javanese are e.g. “Bunga” (bloom), “Kembang” (flower), as well as “Kusuma” (flower) and “Melati” (jasmine) from the Sanskrit. At an 1837 marriage in Haarlem, the bridegroom’s mother is a certain “Kananga van Ternaten” (cf. https://www.openarchieven.nl/search.php?name=Kananga+van+Ternaten), which emphasizes this point.

- The boy died in February 1772 and his wife in October 1773. In his new will, Regionaal archief Leiden, Not. Luzac, 1775: 2335, the sums have to be multiplied by 20 to 40 to give the approximate purchasing power in today’s currency. Interestingly, in Dejean’s Viennese death inventory, a collection of “family portraits” was noted but not individually itemized. (Bleker, Lequin, op. cit. p. 128)

- Gemeente archief Den Haag, Notaris archief nr. 4200, akte nr. 1075; folios 775-786. In Dejean’s final testament made in Vienna in 1793, Anna is not mentioned at all. The possibility that Anna was Dejean’s daughter by a native Indonesian woman can be discounted, as she would certainly have been too young to nurse the children during the sea voyage. She might have been his mistress, in which case she would have been subjected to disinheritance in case of infidelity or another form of perceived misconduct. Dejean had been living steadily at Batavia since 1762 and only got to know Anna Maria Pack, née Buschman, in 1766, when the VOC agent Wilhelmus Jacobus Buschman moved there with his family from the base on Kharg Island. Buschman died after only three months in Batavia in January 1767. The remarriage probably took place at Batavia in the summer.

- Amsterdam Stadsarchief, DTB Begraven 1248, folio p. 155/156. https://www.openarchieven.nl/saa:3696f130-7393-4c56-9a90-fda14e71bbe4 She lived in the Passeerdersstraat, probably dying around age 60-65. Still retaining some small eighteenth-century houses, but outside the prestigious canal terraces, Passeerdersstraat today lies in its original social stratum, having a present-day psychiatric rehabilitation unit. No specific age or other details were recorded at Anna’s death.

- He was given into the care of Theodor Heinrich Ten Noever, a teacher friend of Dejean’s, at Lingen, Prussia.

Acknowledgements

We are immensely grateful to Christelle, Khwan, May, Waraporn, and Manao who saw obvious things which we missed.

FALK STEINS is a professional editor and independent scholar in history working in Wiesbaden, Germany. He studied at Cologne and Aberdeen universities, graduating with an M.A. in History, English and Political Sciences.

STEPHEN MARTIN was a psychiatrist and forensic medical examiner. He now researches art history from Baan Dong Bang Museum, Thailand.

One response

Hi! My name is Tim, i’m a descendent of Jeremias Schultz and have been doing research on the identity of the lady in the portrait for about 1,5 years. I have read your article with great interest! I have a theory of the identity of the lady myself as well, based on archival material, which is completely different. It is very interesting to read about the research you have been doing and your theory sounds compelling as well.

If you’d like to be in touch to share ideas about Jeremias, the portrait and the possible sitter, i’d love to be in touch!

Kind regards,

Tim de Jonge