Mostafa Elbaba

Doha, Qatar

The history of microbiology is a compelling narrative of how humanity slowly unraveled the unseen world of microscopic life. The field has fundamentally transformed medicine, biology, and human understanding of disease. But for millennia, explanations for the origins of life and the causes of illness were rooted in philosophical speculation and ancient medical doctrine passed down with little question.

Around the sixth century BC, Western philosophers experienced a major revolution in their thinking about the origins of life. Anaximander (610–546 BC) was one of the earliest Greek philosophers to propose that life could emerge spontaneously from non-living matter.1 This idea was later expanded by Aristotle (384–322 BC), who compiled previous natural philosophies and explanations for the appearance of living organisms.2,3 Aristotle formulated what is now known as the “theory of spontaneous generation,” which claimed that living creatures could arise from non-living materials without the intervention of a causal agent. Examples included the appearance of animals from the mud of Nile riverbanks, fleas from dust, and maggots in decaying flesh.3 It was believed that a life-generating force was inherent in certain types of inorganic matter, such that living microbes could create themselves if given enough time. For nearly two thousand years, spontaneous generation was considered a scientific fact.4,5 Although the theory has long been disproved, certain aspects of it bear resemblance to modern hypotheses about the origins of life, which suggest that simple living organisms emerged from non-living materials approximately four billion years ago and gradually diversified into the forms seen today.

The “miasma theory” was deeply rooted in ancient medicine and articulated by Hippocrates (460–370 BC) in the fifth century BC9 and was later solidified by Galen (AD 129–216).10 The word “miasma” is derived from the ancient Greek term “μίασμα”, meaning “bad air”, a concept that was widely disseminated in medieval Italy.11,12 This theory posited that epidemic infections like cholera and plague resulted from exposure to miasma, which was produced by decaying organic matter. The possibility that microorganisms existed was considered for centuries, but the concept was not widely accepted since it lacked scientific backing at the time.35

The invention of the microscope is shrouded in uncertainty, although it is generally believed that Dutch spectacle makers Hans and Zacharias Janssen invented the first compound microscope around 1590.13 Despite this innovation, the instrument did not gain immediate widespread use.14 By the early seventeenth century, compound microscopes appeared in Europe, paving the way for significant discoveries.

The mystery of why grapes turned into wine, milk into cheese, or food spoiled persisted until Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723), a Dutchman, became one of the first people to observe microorganisms in 1675.15 Using a microscope of his own design, van Leeuwenhoek improved simple single-lens microscopes by crafting high-quality lenses that could magnify objects up to 200–300 times. This allowed him to observe bacteria, which he described as tiny animals or “animalcules“.15,18 The term “bacteria” was later coined in 1828 by Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg (1795–1876).16,17

During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the theory of spontaneous generation was challenged by Italian biologist Lazzaro Spallanzani (1729–1799).6,7 In 1765, Spallanzani discovered that boiling broth sterilized it and killed any microorganisms present.6 He also found that new microorganisms would only appear if the broth was exposed to air, suggesting that microbes moved through the air and could be destroyed by boiling.7 His experiments showed that microorganisms were not an inherent feature of matter and that hermetically sealed broths remained sterile.6,7

In the United States, physician Charles Delucena Meigs (1792–1869)27 and his son John Forsyth Meigs (1818–1882)28 advanced the view that diarrhea was primarily chemical in nature, with bacteria playing a secondary role. Their writings, including Observations on Certain of the Diseases of Young Children27 and A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of Children28 broadened the idea that foods, particularly fats, were fundamental factors in the pathogenesis of diarrhea.34,40

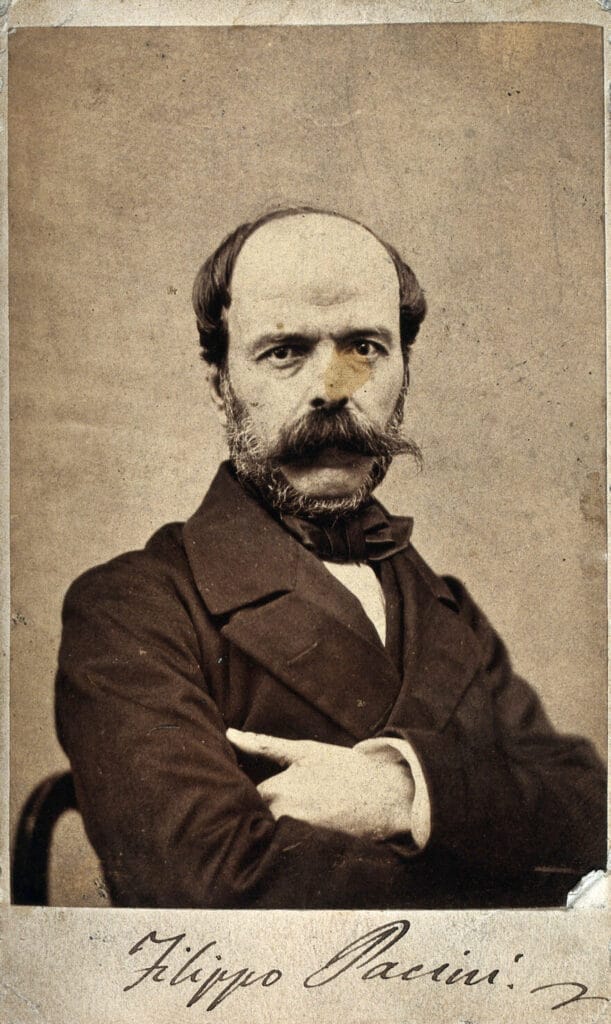

During the third cholera pandemic in 1854, cholera reached Florence, Italy, where Filippo Pacini (1812–1883) became deeply interested in the disease. After performing autopsies on cholera victims and conducting microscopic examinations, Pacini discovered a comma-shaped bacillus, which he named “Vibrio.” In his 1854 paper Microscopical observations and pathological deductions on cholera, he described the organism and its link to the disease.19 However, his discovery was ignored due to the predominance of the miasma theory among Italian scientists.32 Pacini’s work was not recognized until years after his death, despite additional publications.

Swiss botanist Carl Nägeli (1817–1891) had a particular interest in microscopic plant studies, which extended to bacteria. He used the term “fission fungi” to refer to microorganisms that would later be recognized as bacteria. In 1858, he became the first to define bacteria as a separate group.33 Nägeli recognized the role of bacteria in disease transmission, noting that they could be carried by dust particles in the air. In his 1877 textbook, he proposed using physical filters such as wet sponges, layers of wet cloth, or cotton wool pads to intercept dust and reduce airborne infections, recommending their use during epidemics or when visiting the sick.20

Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) expanded on Spallanzani’s findings by exposing boiled broths to the air in vessels fitted with filters to prevent particle entry.8 Pasteur proved that living organisms in such broths came from external sources, like spores on dust, rather than arising spontaneously.8 His experiments dealt a decisive blow to the theory of spontaneous generation and bolstered the “germ theory” of disease.36,38 Pasteur demonstrated bacteria’s roles in fermentation and decay, confirming them as agents of disease21 and initiating the scientific study of microbes. However, while he discarded spontaneous generation, the exact relationship between bacteria and disease was still unclear. There was uncertainty as to whether bacteria were essential causes of disease, since sometimes different bacteria seemed to produce the same disease, and sometimes the same bacteria appeared to cause different diseases. This ambiguity was compounded by experimental inconsistencies and difficulties establishing whether true bacterial invasion of a host had occurred.35

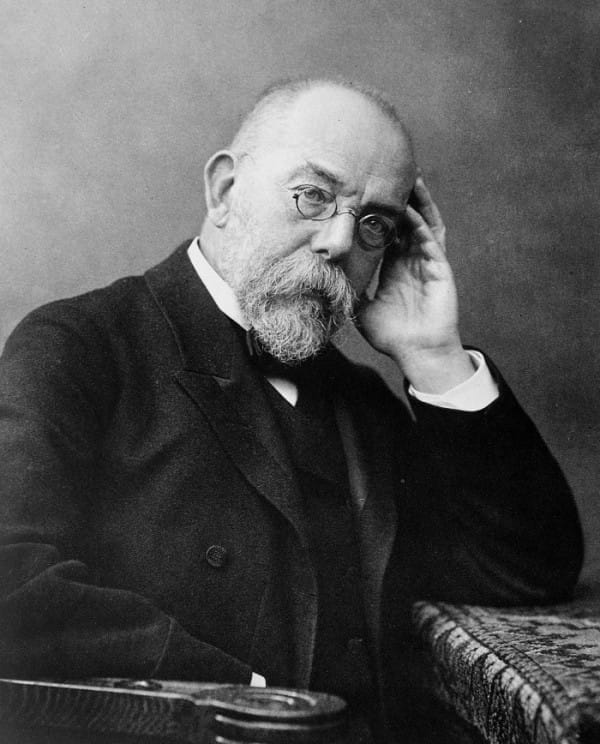

In 1876, Robert Koch (1843–1910) established that microbes could cause disease.22 He observed that cattle with anthrax had large numbers of Bacillus anthracis in their blood. Koch successfully transmitted anthrax from infected to healthy animals by injecting blood or bacteria grown in nutrient broth, demonstrating causality.22 These experiments led him to develop criteria, now known as “Koch’s postulates,” for establishing the causal link between a microbe and a specific disease.24 Koch reaffirmed principles of the germ theory of disease by identifying bacteria that caused anthrax22 and tuberculosis.23 He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1905 for his work.32

Ferdinand Julius Cohn (1828–1898), an extraordinary German biologist, began reading at age two but suffered early hearing impairment. Initially focusing on plant physiology in the 1860s, he shifted attention to bacteria in the 1870s. Cohn was the first to classify algae as plants and to distinguish them from green plants. He categorized bacteria into four basic groups based on shape (Cohn classification): spherical, short rods, threads, and spirals.25 His work laid the groundwork for bacterial classification that is still in use today.33

Max von Pettenkofer (1818–1901), at around age seventy, famously ingested a culture of cholera bacteria to challenge the idea that the bacillus alone caused the disease.26 During Pettenkofer’s career, Koch identified and isolated many bacterial strains, championing the belief that these germs were primary causes of disease. Pettenkofer, however, favored a broader perspective that included environmental factors in disease causation.26 In a notable incident, Pettenkofer drank bouillon containing Vibrio cholerae supplied by Koch, even taking sodium bicarbonate to neutralize stomach acid as Koch suggested. He did not become ill, casting doubt on Koch’s assertion that the bacterium was the sole cause of cholera.37

Hermann Widerhofer (1832–1901), a respected pediatrician and personal physician to Emperor Franz Joseph I, combined pediatrics and geriatrics in his practice. He maintained that certain diseases had pathological rather than bacterial origins, a view he expressed in Gerhardt’s Handbook of Pediatrics.30 Widerhofer held a chair at the University of Vienna, which was later occupied by Theodor Escherich after Widerhofer’s death.

Theodor Escherich (1857–1911) began his work on digestive diseases in 1884, focusing on the fact that Vibrio cholerae was, at the time, the only known pathogenic bacterium linked to a digestive disease. He sought to determine the cause of childhood diarrhea, a major cause of child mortality. Escherich’s research aimed not just to correlate a specific disease with a specific microorganism, but to deepen understanding of infectious processes. During this period, most scientists did not recognize bacteria as the cause of childhood diarrhea.40 He identified new bacteria that he called “bacterium coli commune”, which would later be known as Escherichia coli.29 Escherich himself initially shared doubts, influenced by his mentor Pettenkofer’s skepticism regarding the contagiousness of bacteria.37

Such controversies underscore the scientific process itself: a continuous interplay between revolutionary findings and evidence-based scrutiny. The transition from ancient philosophical speculation to modern microbiology represents one of the most profound intellectual shifts in scientific history. The legacy of pioneering scientists is the entire field of modern microbiology, which continues to deepen our appreciation for the invisible world that shapes all life. This journey highlights key experiments, critical challenges, and the remarkable individuals whose efforts laid the groundwork for modern bacteriology.

References

- Anaximander. (c. 610–546 BC). Doxography on the Origin of Life. (Cited through later commentators and historical philosophical texts like Dicks, D. R. (1970). Early Greek Astronomy to Aristotle. Cornell University Press).

- Aristotle. (c. 350 BC). Generation of Animals. (Book III, Chapter 11 for abiogenesis).

- Aristotle. (c. 343 BC). History of Animals. (Book V for observations cited as spontaneous generation).

- Redi, F. (1668). Esperienze intorno alla generazione degl’insetti (Experiments on the generation of insects). Firenze: Stella.

- Needham, J. T. (1749). A Summary of Some Late Observations on the Generation, Composition, and Decompositon of Animal and Vegetable Substances. London: R. Davis. (Supporting spontaneous generation).

- Spallanzani, L. (1765). Saggio di Osservazioni Microscopiche Concernenti il Sistema della Generazione dei Signori di Needham e Buffon. Modena: G. Montanari.

- Spallanzani, L. (1776). Opuscoli di fisica animale e vegetabile (Tracts on Animals and Vegetables). (Further experiments against Needham).

- Pasteur, L. (1861). “Mémoire sur les corpuscules organisés qui existent dans l’atmosphère” (Memoir on the organized corpuscles that exist in the atmosphere). Annales de Chimie et de Physique, 3rd series, 64, 5–110. (Disproof of spontaneous generation).

- Hippocrates. (c. 400 BC). On Airs, Waters, and Places. (For the environmental basis of disease, foundational to miasma).

- Galen. (c. 175 CE). Hygiene (or On the Preservation of Health). (Reinforcing the role of “bad air” and environmental factors).

- Vitruvius, P. (c. 15 BC). De Architectura (On Architecture). (Discussing marsh vapors and pestilence).

- Halliday, S. (2001). “Death and miasma in Victorian London: an obstacle to a public health.” The Lancet, 357(9271), 1802-1803. (Secondary source on Miasma’s persistence).

- Janssen, H., & Janssen, Z. (c. 1590). Invention of the Compound Microscope. (Cited through historical accounts like Clay, R. S., & Court, T. H. (1932). The History of the Microscope. London: Charles Griffin & Company).

- Hooke, R. (1665). Micrographia: or some physiological descriptions of minute bodies made by magnifying glasses. London: J. Martyn and J. Allestry.

- Van Leeuwenhoek, A. (1677). “Letter to the Royal Society, October 9, 1676.” In Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 12(133), 821–831. (Original description of “animalcules”).

- Ehrenberg, C. G. (1838). Die Infusionsthierchen als vollkommene Organismen (The Infusoria as Complete Organisms). Leipzig: Leopold Voss. (Coined the term “bacteria”).

- Bulloch, W. (1960). The History of Bacteriology. New York: Dover Publications. (Historical context on Ehrenberg).

- Dobell, C. (1932). Antony van Leeuwenhoek and his ‘Little Animals’. London: Constable and Co. (Definitive biography/source on Leeuwenhoek).

- Pacini, F. (1854). Osservazioni microscopiche e deduzioni patologiche sul colèra asiatico (Microscopical observations and pathological deductions on Asiatic cholera). Florence. (Original description of Vibrio).

- Nägeli, C. (1877). Die niederen Pilze in ihren Beziehungen zu den Infectionskrankheiten und der Gesundheitspflege (The Lower Fungi in Their Relation to Infectious Diseases and Health Care). Munich: R. Oldenbourg.

- Pasteur, L. (1879). Études sur la Bière (Studies on Beer). Paris: Gauthier-Villars. (Demonstrating microbes as causal agents in fermentation/spoilage).

- Koch, R. (1876). “Die Ätiologie der Milzbrand-Krankheit, begründet auf die Entwicklungsgeschichte des Bacillus Anthracis.” Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen, 2, 277-310. (Anthrax work).

- Koch, R. (1882). “Die Ätiologie der Tuberkulose” (The Etiology of Tuberculosis). Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift, 19(15), 221–230.

- Koch, R. (1884). Mitteilungen aus dem Kaiserlichen Gesundheitsamte (Communications from the Imperial Health Committee), 2, 1–88. (Formalization of Koch’s postulates).

- Cohn, F. J. (1872). “Untersuchungen über Bacterien.” Beiträge zur Biologie der Pflanzen, 1(2), 127–224. (Foundational work on bacterial classification).

- Pettenkofer, M. von. (1892). The Spread of Cholera in Relation to the Water Supply and Soil. (Cited for his environmentalist view and the context of his challenge to Koch).

- Meigs, C. D. (1840). Observations on Certain of the Diseases of Young Children. Philadelphia: Carey and Hart.

- Meigs, J. F. (1858). A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of Children. Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston.

- Escherich, T. (1886). Die Darmbakterien des Neugeborenen und Säuglings (The Intestinal Bacteria of the Newborn and Infant). Stuttgart: F. Enke. (Discovery of E. coli).

- Widerhofer, H. (1889). “Diathetic and Constitutional Diseases.” In A. Gerhardt (Ed.), Handbuch der Kinderkrankheiten (Handbook of Children’s Diseases). (Cited for his non-bacterial viewpoint on certain diseases).

- Brock, T. D. (1961). Milestones in Microbiology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Lechevalier, H. A., & Solotorovsky, M. (1975). Three Centuries of Microbiology. New York: Dover Publications.

- Pelczar, M. J., Chan, E. C. S., & Krieg, N. R. (1993). Microbiology: Concepts and Applications. New York: McGraw-Hill. (For modern classification and historical overview).

- Porter, R. (1997). The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Ackerknecht, E. H. (1948). “Anti-Contagionism between 1821 and 1867.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 22(5), 562–593. (Context for the persistence of miasma/anti-germ theory).

- Vallery-Radot, R. (1920). The Life of Pasteur. (R. L. Devonshire, Trans.). Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Company. (Historical biography of Pasteur).

- de Kruif, P. H. (1926). Microbe Hunters. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company. (Popular history covering many of the figures).

- Cunningham, A. (1992). “The history of the germ theory of disease.” Journal of General Microbiology, 138(1), 1-8. (Scholarly analysis of the paradigm shift).

- Winslow, C. E. A. (1943). The Conquest of Epidemic Disease. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bynum, W. F. (1994). Science and the Practice of Medicine in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Context on the Meigs, Widerhofer, and Pettenkofer resistance).

MOSTAFA ELBABA is an Egyptian medical doctor, educator, writer and historian. He graduated and was granted a master’s degree in pediatrics from Ain Shams University. In 2011, he settled in Hamad Medical Corporation in Qatar. He has a master’s degree in medical education and advanced certification in medical simulation. Apart from medical qualifications, he is a public author and certified in history of medicine, arts, and religions.