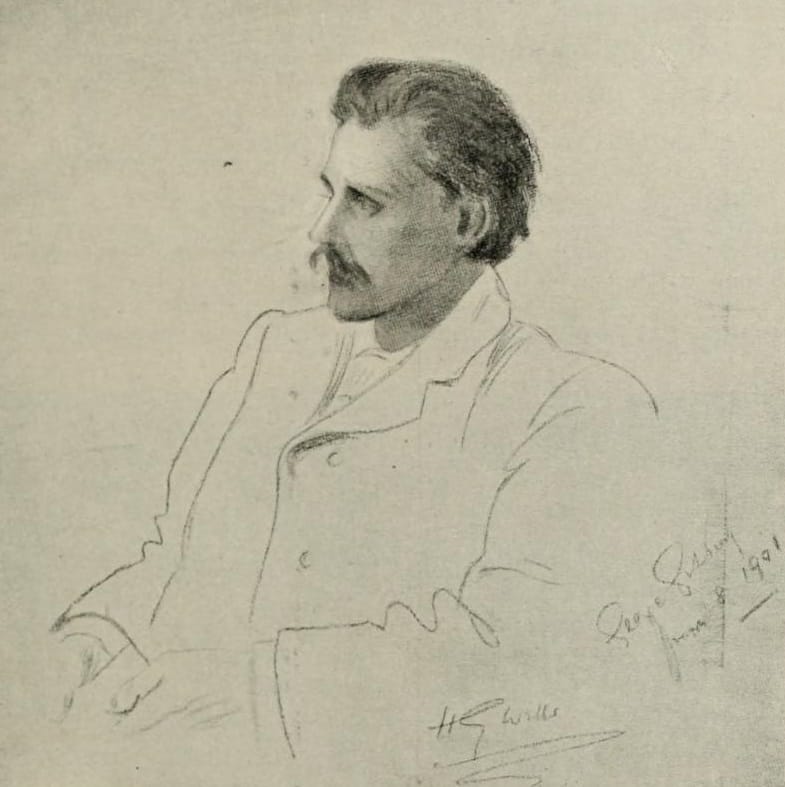

At the end of the nineteenth century, George Gissing (1857–1903) was one of the three most important English novelists of his time. Born in the north of England, he studied at the precursor of the University of Manchester, fell in love with a young prostitute, and began stealing from fellow students to support her. He was apprehended, sentenced to one month in prison, and subsequently dismissed from the college in 1876. For one year he worked in America, leading a precarious existence teaching the classics and writing short stories for the Chicago Tribune and other newspapers. He was a poor man for most of his life and published twenty-three novels, of which New Grub Street (1891) is considered his masterpiece —a cynical and biting look at the commercialism of literary life.

The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft was published shortly before his death.* Combining fiction, autobiography, and philosophical meditation, it is the imagined memoir of a London journalist who, after years of drudgery as a “hack” writer on Fleet Street, receives a modest legacy that allows him to retire and live peacefully in a cottage in the Devon countryside. There, he contemplates life, literature, nature, and society. He reads Virgil, Cicero, and Horace, as well as Charles Lamb and William Hazlitt. He concludes that happiness does not come from public recognition or commercial achievement, but from the quiet satisfaction of enjoying what Aristotle extolled as the contemplative life.

Gissing divided his book into four sections, one for each of the four seasons of the year. In the spring, he is glad not to have touched his pen for seven days and comments that earning money should not be an end in itself; yet, all his life, he has been forced to do so. How wonderful now to enjoy life, its rosy clouds, its beautiful flowers, the singing of birds, to enjoy taking long walks by the seaside, watching the sky, or amusing himself by remembering the names of the plants he sees. He sees the foxgloves in full bloom. The house in which he lives is his, the stairs do not creak under his step; unkind draughts do not waylay him; he can open or close a window without trouble; and as long as he will live, he will have the means to pay the rent and buy his food.

He very much enjoys the good weather. Someday, he will go to London and spend a day or two revisiting the past. He thinks it strange to remember that for several years he never looked upon a meadow, never travelled even so far as the trees of the suburbs. In the winter, he would often experience fierce sore throats, sometimes accompanied by prolonged and savage headaches. However, seeing a doctor never occurred to him; instead, he would lock the door, go to bed, and lie there without food or drink until he was able to look after himself again.

Only occasionally does he wax nostalgic about the bad old days or the occasional good ones, reflecting on what one’s youth should be, reminiscing about all the great books he has read, the sacrifices he had to make to buy them, all the great classical writers of the past, his Gibbon eight-volume edition which he “read and read and read again for more than thirty years”, his Cicero’s Letters, and his great Cambridge Shakespeare. He thinks of The Tempest as the play he loves best, and quotes Doctor Johnson that there is as much difference between a lettered and an unlettered man as between the living and the dead. And yet “foolishly arrogant was I to judge the worth of a person by his intellectual power and attainment. I could see no good where there was no logic, no charm where there was no learning. Now I think that one has to distinguish between two forms of intelligence, that of the brain and that of the heart, and I have come to regard the second as by far the more important.”

And so he goes on, remembering and reminiscing, sometimes judging badly what he once judged favorably, commenting on the great artists of the past, on Goethe, Flaubert, Shakespeare, and Cervantes, on Herodotus and the Anabasis. Then comes summer, and then autumn and winter, and he is still reminiscing. When he catches a cold, which means three weeks’ illness, merely feverish and weak and unable to use his mind, he lies in bed watching the clouds. He remembers that there was a time when he was consumed with a desire for foreign travel, when he went to Brindisi and the coast of Albania, listened to Chopin and admired Turner, but what remains now leaves only enough energy to enjoy this “dear island.” He likes to look at his housekeeper when she carries in the tray. He loves English food, such as roasted beef and boiled leg of mutton. It angers him to see in a grocer’s shop a display of foreign butter and thinks this is one of the worst signs of the moral state of the English people. Sauces are to be utterly forbidden—save the natural sauce made of gravy. Decades before women’s liberation, he thinks little girls should be taught to cook and bake more so intensively than they are being taught to read.

He now reads less than he used to and thinks much more. He thinks of death very often; at one time, he dreaded it, but now no more. Pain he cannot well endure, and he often thinks with apprehension of being subjected to the trial of long deathbed torments. He no longer takes much delight in drinking wine, and as he walks in the golden sunlight, he suddenly thinks that if his life were over, he would not grumble.

- See also: “By George Gissing: The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft. Summer VI,” in Hektoen International.