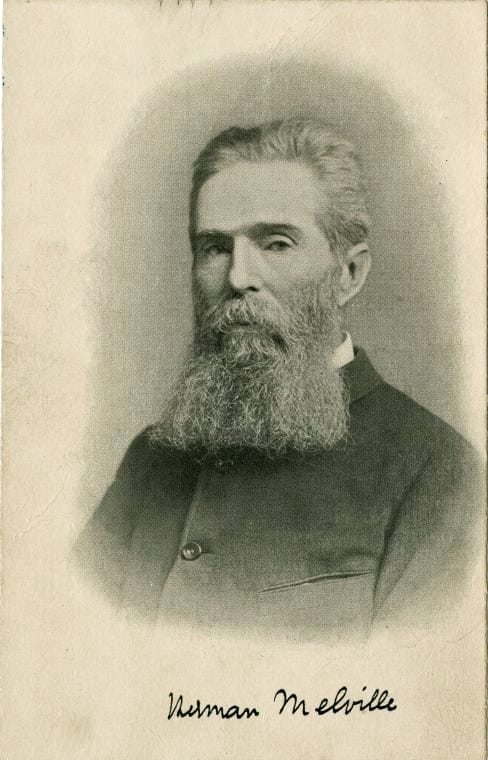

Herman Melville (1819–1891), best remembered for his monumental novel Moby-Dick, was a writer whose life and work were profoundly shaped by medical themes. Although he is often placed within the canon of American Romanticism, Melville’s writings reveal not only philosophical and theological concerns but also a deep engagement with the body, illness, and the medical realities of the nineteenth century. His experiences at sea, his exposure to disease, and his observations of suffering left an imprint on his fiction, while his personal struggles with health and mental well-being underscore the medical lens through which we may better understand his work.

Melville’s early career as a sailor exposed him to the precarious medical conditions of seafaring life. Whalers and naval ships in the mid-nineteenth century were notorious breeding grounds for scurvy, dysentery, smallpox, and venereal disease. Ship surgeons, when present, had limited supplies and rudimentary knowledge. Melville witnessed firsthand how illness shaped the rhythms of life on board, reducing strong men to weakness and contributing to mortality rates at sea. His semi-autobiographical novels, Typee (1846) and Omoo (1847), depict the consequences of malnutrition, infections, and inadequate care among sailors and Polynesian islanders alike. In Omoo, for instance, Melville vividly describes a floating hospital ship in Tahiti, filled with suffering patients, some neglected, others treated with ineffective or even harmful remedies.

Such depictions are not incidental but reflect Melville’s awareness of the fragility of health in an age before germ theory was established. His literary eye translated shipboard infirmaries and improvised surgeries into metaphors of human vulnerability, setting the stage for the medical resonances that pervade Moby-Dick.

Few novels teem with medical imagery as much as Moby-Dick (1851). Captain Ahab, obsessed with vengeance against the white whale, is introduced as a man physically scarred and psychologically disturbed. His missing leg, replaced with a whalebone prosthesis, serves as a powerful symbol of mutilation, resilience, and madness. Ahab embodies chronic pain, a condition poorly understood in Melville’s day but rendered with astonishing psychological depth.

The novel also offers striking anatomical detail: descriptions of cutting into whales, extracting oil, and handling viscera mirror surgical dissection. Ishmael, the narrator, often likens whaling to medical practice, noting how the crew “anatomizes” the whale as though it were a giant patient on the operating table. Melville transforms the whaling industry into a vast medical theater, dramatizing the intimate connections between body, industry, and mortality.

Even metaphors of disease pervade the narrative: obsession is described as a “malady,” the sea as a medium of contagion, and the whale as a pathological enigma resisting diagnosis. Thus, Melville situates the medical both literally and symbolically at the heart of his masterpiece.

Melville himself endured medical struggles. Throughout his adult life, he suffered bouts of what was likely depression, compounded by chronic physical ailments such as back pain and eyestrain from long hours of writing. In the 1850s and 1860s, letters from his family reference his “nervous afflictions,” suggestive of what we might today call mood disorders. His melancholy, combined with financial pressures, led to an emotional breakdown around 1867 after the sudden death of his son Malcolm.

While psychiatry was in its infancy during Melville’s lifetime, he was aware of contemporary medical discourses on madness and melancholy. His later writings, including Clarel (1876), grapple with questions of despair and human suffering in ways that parallel medical case studies of the period. His struggles remind us that Melville was not only a chronicler of illness but also a patient negotiating the uncertainties of nineteenth-century medicine.

Ultimately, Melville’s medical sensibility extended beyond personal experience into a philosophy of existence. He saw humanity as afflicted by what he called the “universal throb of pain,” a condition that linked sailors, captains, and readers alike. His works suggest that medicine, while necessary, could never fully cure the existential wounds of life. The whale’s inscrutability, Ahab’s mutilation, and Ishmael’s survival all converge in a meditation on the limits of healing and the endurance of suffering.

Herman Melville’s engagement with medicine was neither incidental nor superficial. His seafaring background, his depictions of disease and anatomy, and his personal struggles with mental and physical health gave his writing a unique medical dimension. In Moby-Dick and beyond, illness becomes metaphor, dissection becomes narrative technique, and suffering becomes the measure of human existence. To read Melville medically is to appreciate how nineteenth-century experiences of health, disease, and healing were woven into some of the most enduring literature of the American tradition.