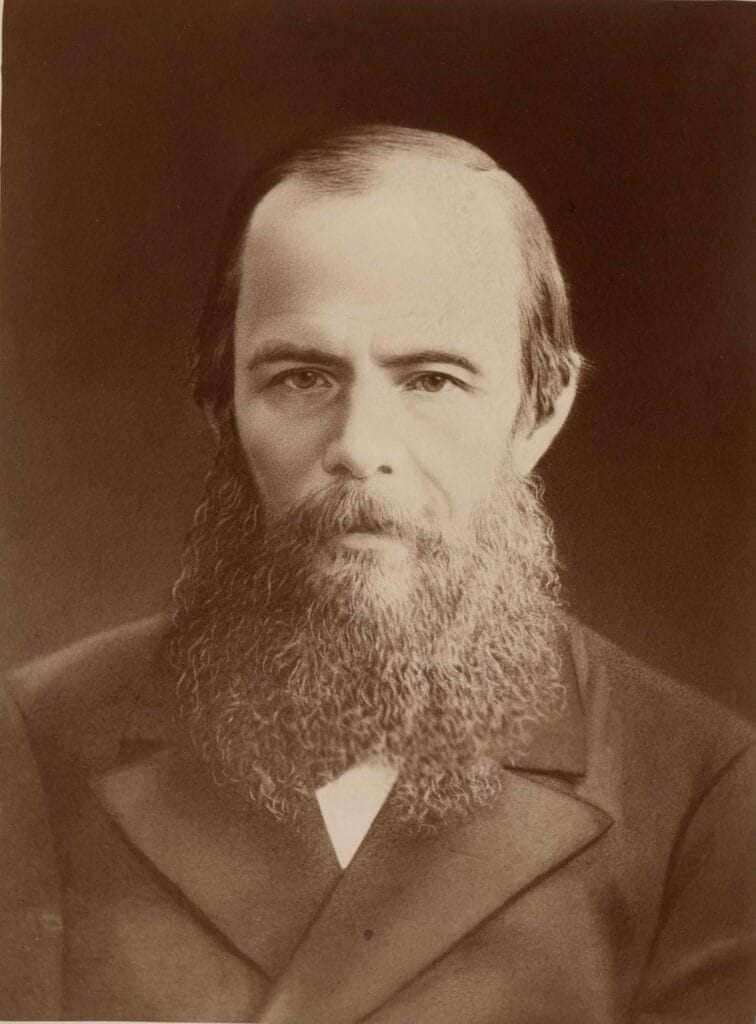

Few literary giants have intertwined so intimately with medicine as Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (1821–1881). His turbulent life and writings reveal an ongoing struggle with chronic illness, psychological torment, and an acute awareness of the body’s fragility. Medicine was not simply a backdrop in his life; it was a decisive force shaping both his biography and the themes of his novels.

Dostoevsky suffered from epilepsy, a condition that appeared in his twenties and remained with him for life. Accounts from his family, friends, and his own notebooks describe convulsive seizures, often preceded by moments of ecstatic aura—a state he later gave to characters such as Prince Myshkin in The Idiot. These auras were not mere clinical phenomena: Dostoevsky interpreted them as mystical illuminations, fleeting glimpses of eternity that were paid for by collapse and exhaustion.

Nineteenth-century medicine had only primitive explanations for epilepsy. The prevailing view was that it signified degeneration, hysteria, or even moral weakness. Dostoevsky’s case thus carried stigma as well as suffering. Yet rather than diminishing his genius, the condition enriched his imagination. His portrayal of epileptic states gave literature some of its most precise and moving descriptions of neurological illness. Prince Myshkin’s seizure in The Idiot remains a textbook example of epilepsy’s clinical and existential impact, blending symptomatology with spiritual insight.

Dostoevsky’s exile in Siberia (1849–1854) exposed him to a grim medical environment. The prison camps were rife with malnutrition, scurvy, typhus, and frostbite. Medical care was rudimentary, often administered by fellow convicts with little training. In Notes from the House of the Dead, Dostoevsky depicts festering wounds, amputations, and crude surgeries—descriptions that reflect his firsthand experience of suffering bodies in confinement.

This encounter with the physical degradation of prisoners sharpened his insight into the links between social injustice, bodily torment, and spiritual endurance. His novels would repeatedly return to the tension between the body’s humiliation and the soul’s resilience, a theme rooted in the penal medicine he observed.

Beyond epilepsy, Dostoevsky’s life was marked by depression, anxiety, and pathological gambling, all of which can be understood in medical as well as literary terms. The nineteenth century saw the rise of psychiatry, yet its treatments were crude—ranging from rest cures to moral exhortation. Dostoevsky’s own psychic crises, often exacerbated by financial ruin, became sources for his explorations of obsession, compulsion, and madness. Characters such as Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment embody psychological torment that borders on clinical psychosis.

His writings anticipated modern psychiatry’s recognition of the unconscious, compulsive behavior, and the destructive cycle of addiction. Gambling, for Dostoevsky, was not mere vice but a disease: a physiological and mental fever whose clinical contours he mapped in his novella The Gambler.

Medical figures—doctors, caretakers, and invalids—appear frequently in his novels. In The Brothers Karamazov, the character of Ilyusha’s illness becomes a communal event, drawing attention to compassion and mortality. In The Idiot, the physician Schneider, who treats Myshkin’s epilepsy, reflects contemporary neurology’s halting progress. These depictions show Dostoevsky’s awareness of medicine’s limits, but also of its ethical significance.

By dramatizing illness, Dostoevsky blurred the boundaries between patient and physician, body and soul, science and morality. He anticipated questions that remain central in medical humanities: How does illness shape identity? What does suffering teach us about human dignity?

In his later years, Dostoevsky’s health deteriorated. He suffered repeated hemorrhages, probably from emphysema and chronic lung disease, compounded by epilepsy. Despite medical attention, treatments of the time—bloodletting, poultices, narcotics—were ineffective. He died in 1881 after a pulmonary hemorrhage, surrounded by family and readers who already sensed his status as a prophet of the human condition.

Dostoevsky’s life was inseparable from medicine—through the seizures that tormented him, the penal hospitals he endured, the psychological compulsions he dramatized, and the doctors and patients he placed within his novels. His works remain not only literary masterpieces but also documents of medical history, capturing how illness, in both body and mind, can shape vision and creativity. In Dostoevsky’s world, medicine was never merely clinical: it was existential, philosophical, and deeply human.