New Guinea is the second-largest island in the world that is not a continent (after Greenland). It is divided into the Republic of Papua-New Guinea in the east and a western area that belongs to Indonesia. In both parts, indigenous populations face significant health challenges because of poverty, parasitic diseases, and poor medical facilities. Of more worldwide interest, however, has been the rare neurological disease called “kuru”. This once affected the Fore people of the Eastern Highlands of Papua New Guinea, a small tribe of some 8,000 people living in small hamlets 1,500 meters above sea level.1,2 The term “kuru”, meaning to shake or tremble, is derived from the Fore word “kuria” or “guria.”

Kuru now appears to have been eradicated. It first affected its victims with an unsteady gait, tremors, and a slight loss of coordination. Mood changes, depression, or occasional bursts of uncontrollable laughter followed, giving the disease its nickname “the laughing death.” It progressed to tremors, muscle jerks, an inability to walk without support, marked emotional instability, and cognitive decline. Muscles became wasted, and patients became bedridden, could not swallow, were incontinent, and died from pneumonia or other infections.

The disease was noted in the 1930s, or perhaps even earlier, by gold prospectors and missionaries.2 Around 1948, Australian government officers, anthropologists, and medical assistants observed an increasing number of cases among the Fore, who called it kuru and attributed it to sorcery or witchcraft.2

By 1950 anthropologists such as Shirley Lindenbaum and Michael Alpers had carried out epidemiological investigations and discovered that it was transmitted among the Fore people by endo-cannibalism,2 the practice of eating the brain of dead relatives as part of ritualistic funeral practices. The disease was about nine times more common in women and children because it was they who consumed the brains of their dead relatives. The disease had an incubation period ranging from four to over fifty years.2 Eventually the work of Australian colonial law enforcement and local Christian missionaries resulted in largely abolishing this disease by about 1960.

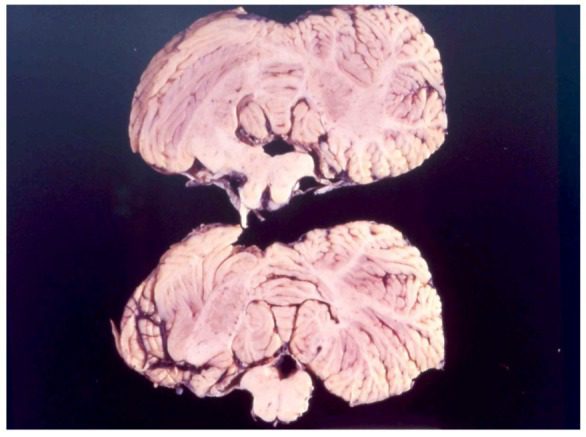

Further studies carried out in the 1950s, some under the aegis of the United States Medical Research Council, notably by Drs. Vlacovas (“Vin”) Zigas and Daniel Carleton Gajdusek, confirmed that kuru was being spread by personal contact. Direct passaging of the disease by Gajdusek and his team to chimpanzees and other primates conclusively proved its transmissibility, a finding for which Dr. Gajdusek received the Nobel prize in 1976. Some time later, Dr. Stanley Prusiner also received the Nobel Prize for showing that the infection was caused by a prion, a variant protein distinct from bacteria, viruses, and fungi by not containing any nucleic acids. The research on kuru eventually led to its elimination, its last known death occurring around 2005 or 2009. The disease is now of historical interest only, but the research it engendered insights into the mechanisms of prion propagation in the similar neurological diseases Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, bovine spongiform encephalopathy or mad cow disease, scrapie (spongiform encephalopathy in sheep), transmissible mink encephalopathy, feline spongiform encephalopathy, and ungulate spongiform encephalopathy.

Further reading

- Kuru (disease). Wikipedia.

- Radford A and Scragg R. Discovery of Kuru Revisited: How Anthropology Hindered Then Enhanced Kuru Research. Health and History 1013;15(2).

Leave a Reply