Stephen Martin

Thailand

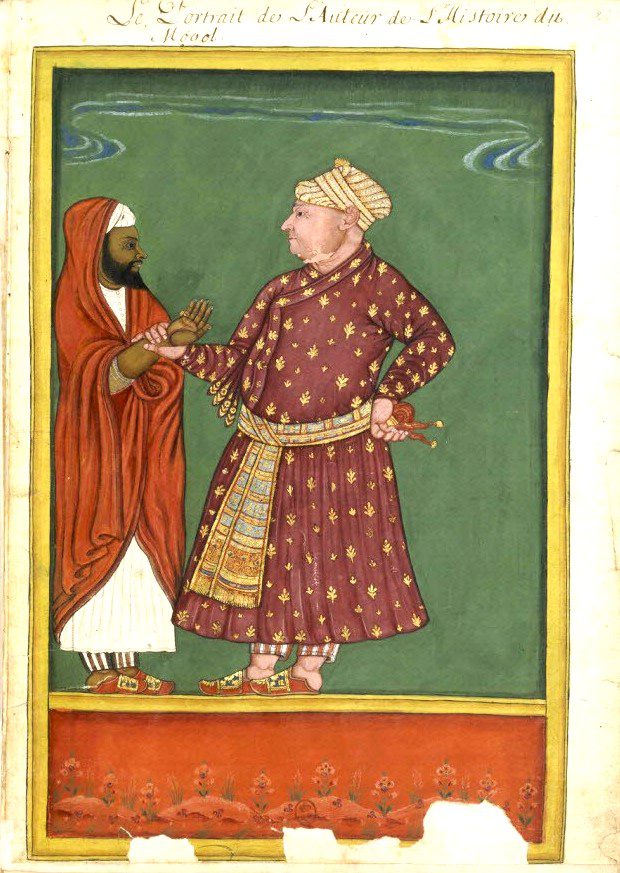

A teenage stowaway on a ship from Venice in 1653 had an unusual route into medicine. He was Nicolò Manucci (1638–1720, Fig 1). The earliest image of him gathering medicinal herbs in India is in the style of a Moghul imperial artist, probably done in Aurangabad, judging by the pink and brown color of the igneous rocks there, unlike around Delhi. Not only did he spend the rest of his life in India, he later compiled an extraordinary account of his adventures in his Storia do Mogor.1 It was translated into English in 1907 for the Royal Asiatic Society, giving a long and detailed history of Moghul India at the time.

Manucci became interested in medicine, initially studying in India with Jesuit priests. He had a friend send him medical textbooks, becoming a largely self-taught physician. Manucci served as chief physician to Prince Shah Alam, the eldest son of the Moghul Emperor Aurangzeb. He had been impressive in treating an unnamed wife of the Shah for a serious illness, and secretly, for an ear abscess. Her parents knew of his previous successful reputation in Lahore. He was therefore appointed on a salary of 300 rupees a month and given the noble title Mansabdar. Manucci resided in Aurangabad (renamed Sambhajinagar), capital of the central Deccan principality and elsewhere. He refused to serve under the existing Persian chief doctor and worked independently from him and the other doctors, whose jealousy he faced constantly. Manucci commissioned Indian court artists to paint some of the characters and scenes he experienced, which still survive in Paris.

The Shah’s young chambermaid, Dil-jo, had a mental disorder.2 She “suffered from insomnia, and from time to time frightful things overtook her, even to biting her own body.” Manucci’s imaginative remedy was to recommend that she marry. She had a baby and went into full remission. It caught on and other women in the court urged Manucci to prescribe marriage for their feigned illnesses. He obliged and it helped his historical research: “These people were subsequently very grateful for the kindness I had done them, and gave me proof of it from time to time. Thus it is through them that I have been informed of many particulars as to what went on in the court of this prince.”

He also did some of what is now forensic psychiatry. The Shah’s brother-in-law3 “slew his father-in-law and some servants, and committed many other crimes. On hearing this the prince gave him over to his physicians. Their report was that such a man could never recover the senses that he had lost.” Manucci calmed the patient down and he was well in a few days, much to everyone’s gratitude, and he was forgiven by the Shah. He treated an enraged man with restraint and bleeding:4 the “king’s slave [was] in a great rage and a great hurry, making much noise and throwing everything into confusion. This, man, I imagine, had been sent by the other doctors, my enemies.” The patient vehemently refused to be bled, threatening to kill Manucci’s assistants who restrained him for bloodletting:5

I assumed an aspect of mingled severity and sadness, and said I had compassion for him, seeing he was suffering from blood to the head … ignoring what he said, I showed sorrow at beholding his blood, from time to time feeling his pulse and saying that his blood was very vitiated. Then, raising my eyes, I looked in his face and asked if he did not already feel an alteration in his body. Finding that his menaces and loud talk were of no good to him, nobody listening to them, he adopted at last the mode of humble entreaty, and said in a feeble voice that God had brought him to my house to be cured of the ills he had suffered from through many years. He thanked me for my trouble.

Manucci was inventive. Faced with a moribund, elderly native woman, apparently with intestinal obstruction, he gave an exotic herbal enema delivered from a cow’s bladder. The effect was full recovery, much to her gratitude. Manucci fed a man with wasting and anorexia a comforting syrup and horse stew,6 which restored him to his “former rude strength.”

Moghul civilians under the Emperor Aurangzeb were taken prisoner under his rival, the Sultan of Bijapur, with whom he was at war. They had their noses cut off in punishment, shame, and stigma. In 1670, Manucci observed the procedure of cutting and stitching forehead skin flaps to reconstruct the nose. He described it in the Storia:7

The campaigns against Bijapur began from 1670, and lasted until this year (1686). At the commencement of the war, when the men of Bijapur caught any unhappy persons belonging to the Moguls who had gone out to cut grass or collect straw or do some other service, they did not kill them but cut off their noses. Thus they came back into the camp all bleeding. The surgeons belonging to the country cut the skin of the forehead above the eyebrows, and made it fall down over the wounds on the nose. Then, giving it a twist so that the live flesh might meet the other live surface, by healing applications they fashioned for them other imperfect noses. There is left above, between the eyebrows, a small hole, caused by the twist given to the skin to bring the two live surfaces together. In a short time the wounds heal up, some obstacle being placed beneath to allow of respiration. I saw many persons with such noses, and they were not so disfigured as they would have been without any nose at all, but they bore between their eyebrows the mark of the incision.

Just over a century later, The Gentleman’s Magazine described and illustrated the forehead flap operation on an Indian, punished by Tipu Sultan with nose amputation.8 The use of ghee oil with successful plastic surgery by an Indian brickmaker is astonishing. The Magazine’s editor9 intelligently described to the general readership that the English Chirurgorum Comes of 1687 had also recorded the flap technique for facial plastic surgery. It was based on Tagliacozzi’s Italian account of the late 1500s.10 The procedure appears to have originated in India, though, where it was obviously widespread and well-established by the 1600s, perhaps from late medieval origins, if not older still. In Europe, it was largely if not completely confined to rare textbooks.

Manucci had a notable knack of ingratiating himself with anyone of importance. François Martin, the Governor of French India based in Pondicherry, helped Manucci in late 1682/early 1683 with a boat from Surat on the Deccan coast, ostensibly to go on leave from the Shah’s court to Goa. Manucci’s real plan was to access his money there and flee the unrealistic demands and jealousy of the war-torn Moghul courts altogether. One pressure on him was that he was perceived to have magical powers as a Christian, and the court expected him to transplant a whole face. He succeeded for a while, but he was forced to return to work under escort for Shah Alam, until finally absconding to Madras on a trip to Hyderabad. The image of a rotund Manucci feeling a patient’s pulse (Fig 2) probably shows him around age forty-five in Aurangabad, as that would have been his last chance to commission paintings by Imperial Mughal court artists. It is by a different and superior artist to that of him in Fig 1. His later residences of Pondicherry and Madras were cultural deserts for both European and Indian painting at the time.

In 1686, Governor Martin advised Manucci not to return to Europe, but to concentrate on history and to marry Elizabeth Hartley, daughter of Donna Aguida Pereyra, a Portuguese woman. He agreed. Manucci’s father-in-law was a company president in Machilipatnam. All this time Shah Alam was sending out envoys to look for Manucci to make him return to his court medical work. His eagerness to leave and pursuit by native employers matches that of William Hamilton, who was physician to the later Moghul Emperor Farrukhsiyar in Delhi.11

In 1704, well into his sixties, Manucci (written Manuzzi in French documents), had settled in the south and was still a friend of the Martin family, witnessing with the old governor the wedding in Pondicherry of his granddaughter, Agnes Desprez.12

Manucci lived to be eighty-two, and while his will survives, the place of his death and burial are not known. That lacuna suggests he died in Madras, because the surviving French public records from India at the time were far superior and seem exhaustive.

The Portuguese in Manucci’s book, including his name spelt Niccolao, may stem from Donna Aguida or Elizabeth working on the text with him, as his own level of written literacy has been questioned.13,14 Manucci sent copies in French, Portuguese, and Italian back to Europe. Somewhat recognizably today, in his later career Manucci concentrated on medical humanities, with less work in clinical medicine and more in history. His history has stood the test of time in its interest. So, too, have his psychological techniques and the astonishing Indian plastic surgery which he observed 350 years ago.

End notes

- Manucci N. Trans. William Irvine. Storia dol Mogor. The Indian Texts Series I, John Murray, London for the Royal Asiatic Society, 1907. Vols 1-4. Archived at:

- Vol 1 https://archive.org/details/storiadomogororm01manuuoft,

- Vol 2: https://archive.org/details/storiadomogororm02manuuoft,

- Vol 3: https://archive.org/details/storiadomogororm03manuuoft,

- Vol 4: https://archive.org/details/storiadomogororm04manuuoft.

- Manucci’s detailed account in all of the volumes remains very readable. His medical experiences are concentrated in Vol. 2.

- Manucci, op. cit., Vol 2, p. 392.

- Manucci, op. cit., Vol 2, p. 404.

- Manucci, op. cit., Vol 2, p. 407.

- Manucci, op. cit., Vol 2, p. 408.

- Manucci, op. cit., Vol 2, p. 406.

- Manucci, op. cit., Vol 2, p. 301.

- Chauhan N. Of honors lost and honor regained: Indian origin of plastic surgery. Hektoen International, Asia (India), Spring 2019. https://hekint.org/2019/05/07/of-honors-lost-and-honor-regained-indian-origin-of-plastic-surgery/ Describes the illustrated facial flap procedure in the eighteenth century in full.

- Urban, Sylvanus. Pen name of managing editor John Nichols. Illustration engraved by Barak Longmate the younger. The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle, 1794. Vol. 64. Part II, October 1794, pp. 891-92 and plate I, at p. 883. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hw290x&seq=333 Accessed April 2024.

- Tagliacozzi G. De Curtorum Chirurgia per Insitionem. Gaspari Bindoni the younger, Venice, 1597.

- Martin S. Medical monuments in St. John’s Church, Kolkata. Hektoen International Art Essays, Fall 2023. https://hekint.org/2023/12/14/medical-monuments-in-st-johns-church-kolkata/

- Archive de la compagnie française pour le commerce des Indes orientales: Pondichery, 1704. Ed. Porto A. 17.11.22. Lepetitjournal.com, accessed April 2023.

- Notes for exhibition: Nicolò Manucci, the Marco Polo of India. 29 April – 26 November 2023. Fondazione dell’Albero d’Oro, Palazzo Vendramin Grimani, Venice 2023. https://www.fondazionealberodoro.org/exhibitions/nicolo-manucci-the-marco-polo-of-india/

- Moneta M. Trans. Ruscone E G. A Venetian at the Mughal Court. Penguin Random House India, 2021.

STEPHEN MARTIN is a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society and honorary professor of psychiatry who voluntarily runs a museum and education project in Thailand.