Julius Bonello

Cassandra Palmer

Peoria, Illinois, United States

“The inspiration of a noble cause involving human interests wide and far, enables men to do things they did not dream themselves capable of before, in which they were not capable of alone. The consciousness of belonging, vitally, to something beyond individuality; of being part of a personality that reaches we know not where in space and time greatens the heart to the limit of the souls ideal and builds out the supreme of character.”

– Joshua Chamberlain, October 3, 1889

Monument Dedication, Gettysburg, PA

Deadly fighting had been raging most of the day when the Union’s 20th Maine marched onto the battlefield on the hot afternoon of July 2, 1863. The Union Army had been defeated the day before just west of the small town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. They had retreated through town and set up a new defensive line. Almost two miles long, it extended from the town’s cemetery south to a small hill called Little Round Top. Along this line, about 75,000 federal troops were actively engaged with the Confederate Army when the 20th Maine arrived under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Joshua Chamberlain.

Col. Chamberlain’s brigade commander Colonel Vincent was charged with holding the Union’s left flank just below the summit of Little Round Top. He appointed the 20th Maine to be on his extreme left with these words: “I place you here. This is the left of the Union line. You understand you are to hold this ground at all costs.” Chamberlain knew that if he failed, the line would be flanked and the Union Army could be routed.

The fighting on Little Round Top lasted throughout the day. It was fierce, deadly, and on a few occasions hand-to-hand. Commander Vincent was shot and killed while leading the brigade. In the late afternoon, because there were no reinforcements or supplies, the 20th Maine was running low on ammunition. Chamberlain had two options: one, to retreat; and two, to continue fighting until all ammunition was gone. He decided on a third: a charge, hoping that surprise and holding the upper ground would stop the advancing Confederates. Shouting “Fix bayonets!” his troops descended on the Confederate soldiers. Believing reinforcements had arrived, the Southern soldiers retreated. The charge was a resounding success with the Confederates being routed and the 20th Maine taking 400 prisoners. By his actions that day, Chamberlain had both secured the left flank for the Union Army and forever secured an honored place in the annals of American history. Later that year, Chamberlain, now with the moniker “The Lion of Little Round Top,” was rewarded with the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain (1828–1914) was born in Orrington, Maine and was the oldest of five children. Growing up he enjoyed outside activities such as horseback riding and sailing, but shied away from group activities because of a minor speech disorder which continued throughout his career. As a young man, he worked odd jobs, including as a laborer in a lumberyard before accepting a teaching job in 1846. He matriculated into Bowdoin College in 1848 and graduated in 1852. He then enrolled at Bangor Theological Seminary, graduating in 1855. Instead of becoming a minister, he returned to teach at Bowdoin College. In December 1855, he married “Fanny” Adams to whom he had been engaged for two years. They had five children with only two surviving to adulthood.

Chamberlain first taught at Bowdoin College as an instructor of logic and theology. He succeeded Professor Calvin Stowe (husband of Harriet Beecher Stowe), who had taken another position. After only a year, he was promoted to professor of rhetoric and oratory. Four years later, in 1861, he was named professor of modern languages, assuming the chair originally created for Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in 1829.

During these academic years, by attending biweekly meetings with the Bowdoin faculty, Chamberlain became close friends with the Stowes and familiar with their involvement in the rapidly changing state of American society. The wide acceptance of Harriet Beecher’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin was finally laying bare the evils of slavery and fueling the anti-slavery movement. Chamberlain became an ardent follower.

With the secession of South Carolina in December 1860, and the firing on Fort Sumter by rebel forces on April 12, 1861, Chamberlain’s life was abruptly changed. The thirty-three-year-old father of two children denounced the South’s withdrawal from the Union, stating that “the best of virtues may be enlisted in the worst of causes.” He, along with 300 students from Bowdoin College, immediately offered their services to the Union. After conferring with the military’s commanding officers, he turned down a leadership position in the newly formed Maine’s 20th regiment. He preferred “to start a little lower and learn the business.”

The 20th Maine, after being kept in reserve at Antietam, saw its first action at Fredericksburg. There it was part of the failed Union attack on Marye’s Heights. Chamberlain and the other men of the 20th spent the cold December night hiding behind fallen comrades while Minié balls passed overhead. They retreated the next morning during a truce granted by Robert E. Lee.

After Fredericksburg, the 20th Maine experienced an outbreak of smallpox, which prevented it from being involved in the Battle of Chancellorsville. However, Chamberlain asked to be transferred to another regiment, where he helped with the Union’s withdrawal. Because of his actions at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, Chamberlain was promoted to Colonel. He returned to the 20th Maine, which had rejoined the federal troops following General Lee now heading north. Lee, with hopes of relieving his beloved, war-torn Virginia, planned to destroy the Northern Army in their own backyard, thereby threatening Washington and lowering the morale of the Northern citizens. His goal was Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, yet they clashed at Gettysburg. After Gettysburg, Chamberlain was assigned to the third brigade first division. With this brigade, he participated in the Culpepper and Centerville campaigns in November 1863.

Following a short bout of malaria, he participated in the battles of Bethesda Church and Cold Harbor. In June 1864, Chamberlain was again promoted and was assigned command of the First Brigade First Division Fifth Corps composed of six Pennsylvania regiments, which he led during the Petersburg Campaign.

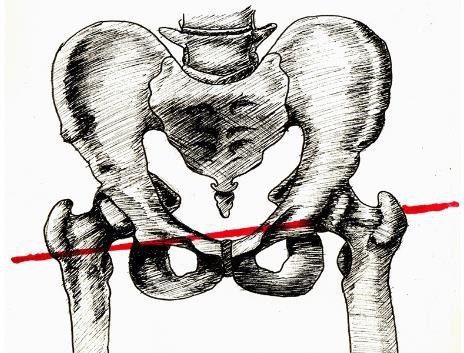

On June 18, 1864, while leading his men in an assault at Petersburg Virginia, Chamberlain was shot by a ricocheting Minié ball. The bullet entered his right hip obliquely, tearing through his bladder and urethra, and emerged behind his left hip. Not wanting to worry his men, Chamberlain jabbed his sword into the ground and leaned on it for support. With blood running down both legs and filling his right boot, he eventually became weak and crumpled to the ground. Medical personnel who reached him thought the wound was mortal and issued a death notice. A New York paper even issued his obituary the next day.

Chamberlain was carried by stretcher three miles to the nearest field hospital. Here surgeons, including Dr. Abner Shaw, a fellow soldier from Maine, operated on him during the night. They removed the bullet and managed to patch him up enough that they concluded there might be a chance for recovery.

General Ulysses Grant, the Union commander, was advised of Chamberlain’s possible mortal wound. Because he had the authority to promote officers on the field for acts of gallantry, on June 18, he promoted Chamberlain to Brigadier General.

The next day, Chamberlain was transferred to the Naval Hospital in Annapolis for rehabilitation. Over the next six months his wounds healed, but he was left severely disabled with a bladder fistula, an external opening from his bladder that drained urine continuously onto his skin. This caused severe pain and swelling to his perineum and scrotum and required the occasional use of an in-dwelling catheter. At only thirty-five years old, Chamberlain was likely permanently impotent as a result of his injury.

Because of his unwavering loyalty to the Union, and despite his lingering wounds, in November Chamberlain asked Grant for another active role in the war. He led his regiment in two battles before he, honored by Grant, accepted the surrender of Lee’s army at Appomattox.

After the war, Chamberlain returned to Maine a national hero. Immensely popular, he ran for governor and served four consecutive terms from 1866–1870. After leaving office, he returned to Bowdoin College, where he served as the president until 1883. During this time, Chamberlain suffered constant pain in both hips and lower abdomen in addition to recurrent episodes of infection, which led him to leave his presidential duties for extended periods of time.

Chamberlain’s bladder fistula ultimately required four subsequent surgical procedures. The first was in Philadelphia in 1865, the second in 1866, the third in 1883, and the final procedure was performed in 1893 in New York City. All of these failed, and the fistula remained patent. For the remainder of his life, Chamberlain had to wear either a diaper or a contraption to catch his urine. A quiet, stoic man, Chamberlain kept his malady to himself and hid his disability behind a strong work ethic.

Chamberlain died in 1914 at the age of eighty-five. The cause of death was an overwhelming infection resulting from his pelvic wound. He is considered by some the last casualty of the US Civil War.

References

- Harmon, William and Charles McAllister. “The Lion of the Union: The Pelvic Wound of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain.” Journal of Urology 163, no. 3 (March 2000): 713–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-5347(05)67789-0.

- Lightner, Deborah and Bruce Evans. “The Pelvic Wound of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain Revisited.” Journal of Pelvic Medicine and Surgery 15, no. 6 (November 2009): 449–53. https://doi.org/10.1097/spv.0b013e3181c29c78.

- Reckling, Frederick and Charles McAllister. “The Career and Orthopaedic Injuries of Joshua L. Chamberlain.” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 374 (May 2000): 107–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003086-200005000-00009.

JULIUS BONELLO, MD, is a Professor Emeritus of Clinical Surgery at the University of Illinois College of Medicine Peoria. Though clinically retired since 2020, he takes an active role in the education of medical students and continues to write on the history of medicine.

CASSANDRA PALMER graduated from medical school at University of Illinois College of Medicine Peoria in 2023 and is now a Urology resident at University of Illinois College of Medicine Chicago.

Leave a Reply