Peter de Smet

Nijmegen, Netherlands

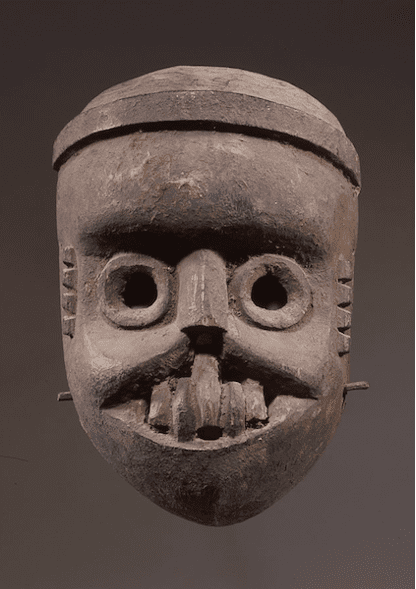

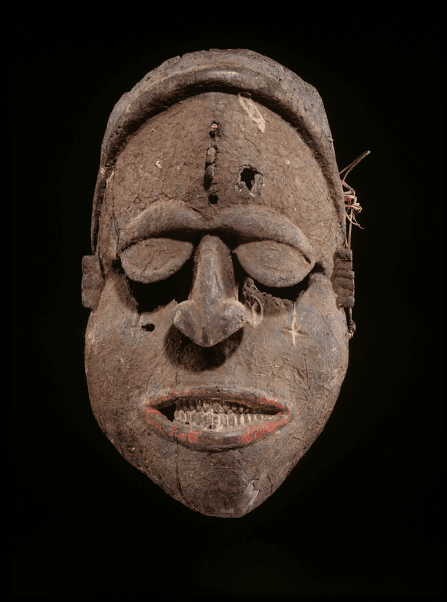

The Ibibio and Igbo peoples in southern Nigeria commemorate their deceased ancestors in masquerades, in which beautiful masks depict good ancestors, while ugly masks portray those who roam about as spirits inflicting illness and misfortune if moral laws are broken. These ugly masks may show twisted or eaten-away noses and lips, sores, and flapped (blind) eyes (Figs 1-2) to remind spectators what could happen to them if they leave the path of righteousness.1-8

An interesting clinical question is whether one could submit such grotesque masks to a diagnostic gaze. This issue is discussed in an art catalogue about African “deformity masks.”8 Semantically, the label “deformity masks” is not optimal, since it only covers masks with a distorted or misshapen appearance (Fig 1) and does not include masks with signs of other conditions such as blindness (Fig 2). Other sources label such masks as “disease masks,” “illness masks,” or “sickness masks.” Hofmann associates these terms, respectively, with a professional perspective, a first-person perspective, and a societal perspective.9 This explains why the term sickness mask is preferred in the present article: disease is too much of a biomedical label, while illness does not reflect very well that the masks are meant to provoke a response in their spectators.

The second chapter of the aforementioned catalogue offers the etic perspective of an outsider by reviewing which diseases may be portrayed by African sickness masks.10 In contrast, the first chapter offers an emic perspective by looking at the sickness masks from the cultural inside. This first chapter emphasizes that such masks may defy identification as specific biomedical conditions because their carvers were at liberty to distort or exaggerate signs of disease and could even create novel disease-like features.11

At first glance, these two approaches seem to be conflicting: the emic view seems to invalidate the viability of etic medical interpretations. However, as long as one keeps in mind that the masks do not have the same accuracy as a Frank Netter anatomy atlas, there is no compelling need to abandon the biomedical perspective altogether. In his book review of the catalogue, Imperato acknowledges that some sickness masks are not manifestations of a specific disease, but he adds that other masks clearly depict disease states.12 A good argument for this latter point of view is that some Ibibio and Igbo informants have associated certain sickness masks with diseases such as leprosy.13,14

Although it is permissible to suggest Western disease labels for some West African sickness masks, it would be unwise to do so unreservedly. There is also an important biomedical reason to be cautious: it can be difficult to distinguish a specific medical condition from differential diagnostic possibilities. A good example is the Ibibio sickness mask in Fig 1. The nasal destruction of such masks has often been regarded as a sign of gangosa, a condition characterized by destruction of the nose that occurs in the late stages of yaws.3,6,13,15,16 However, Klaas Marck, the former president of the Dutch Noma Foundation (personal communication), cautioned that this type of sickness mask could also represent noma, a gangrenous condition of the face that usually occurs in poorly nourished children.5 Marck added that the mask in Fig 1 might also depict syphilis, Buruli ulcer, skin cancer, or a traumatic injury. According to Marck, the Ibibio mask in Fig 3 could not only represent noma, but also skin cancer or goundou, which is a thickening of the upper jaw from yaws that results in large swellings on either side of the nose (Fig 4).

In publications about the sickness masks from southern Nigeria, the most common biomedical suggestions are gangosa, leprosy, and facial paralysis. It should be noted that facial paralysis may be due to leprosy.3-5,10,13,17-20 Another biomedical suggestion that surfaces is noma.21-23 More rarely, a mask may be associated with blindness,1,24 large skin lesions,25 or Burkitt’s lymphoma.4

The masks in Figs 4 and 5 add another possibility. Chinyere Pedro-Egbe, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Port Harcourt (personal communication) believes that the lump on the eyeball in Fig 4 may represent anterior staphyloma, a localized protrusion of uveal tissue that results from a defect in scleral thickness. A major underlying cause is traumatic injury that may occur in activities such as chopping firewood26 or with the use of traditional eye medications.27 Staphyloma may also follow an infection. For instance, it may result from corneal ulceration from measles in malnourished children.28,29

The two lumps on the eyeball in Fig 5 could likewise portray staphylomas (Chinyere Pedro-Egbe, personal communication). According to Simmons, the twisted nose of such masks most likely represents a tertiary form of yaws.13 However, yaws does not typically have a direct effect on the eyes. A more plausible possibility might be leprosy, which can produce both nasal asymmetry30,31 and staphyloma32 (Fig 6). The theme of a twisted nose is also present in the False Face masks of the Native American Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) people, who regard it as the mythological result of a traumatic injury,33 which might also lead to staphyloma. Last but not least, the Ibibio carver of the mask in Fig 5 could also have taken the liberty of combining two unrelated signs.5

Wood. H. 29 cm. Author’s collection

Prov: Theodoor Vossenaar, Oss, NL

Photo: Ferry Herrebrugh

Reproduced from De Smet,6 p. 29, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Wood. H. 46 cm

Wereldmuseum, NL, inv.no. AM-105-9

Reproduced from Wereldmuseum

CC BY-SA 4.0

Author’s collection. Prov: Lars and Annabel Olsen, Copenhagen

Comparable examples: British Museum, London,

inv.no. Af1972,35.1; National Museum of African Art,

Washington DC, inv.no. 97-8-1. Photo: Peter De Smet,

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Wood. H. 28 cm.

Prov: Jo De Buck, Brussels

Photo: Anne Deknock, © Jo De Buck, Brussels

Reproduced with permission from De Buck.7

Wood. H. 21.5 cm. Author’s collection

Prov: Jean-Jacques Mandel, Paris

Collected in southern Nigeria in early 1970s

Photo: Peter De Smet. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

and staphyloma. Reproduced with permission from Poon,

et al. 1998:Fig.1a. © Alexander Poon. Royal Victorian Eye

and Ear Hospital, Melbourne.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the expert help of Herbert Cole, Klaas Marck, and Chinyere Pedro-Egbe and the kind permissions of Jo De Buck and Alexander Poon to reproduce Figs 4 and 6.

References

- Messinger, JC. “The Carver in Anang Society.” In: The Traditional Artist in African Societies, WL D’Asevedo, ed. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1973): 101-127.

- Blier, SP. Beauty and the Beast: A Study in Contrasts. New York: Tribal Arts Gallery Two, 1976

- Wittmer, MK and W Arnett. Three Rivers of Nigeria: Art of the Lower Niger, Cross, and Benue from the Collection of William and Robert Arnett. (Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 1978).

- Vossenaar, T. Ziektemaskers uit West Afrika. (Heusden: Galerie Tegenbosch, 1989).

- De Smet, PAGM. “Traditional pharmacology and medicine in Africa: ethnopharmacological themes in sub-Saharan art objects and utensils.” J Ethnopharmacol 63, no. 1-2 (1998):1-175.

- De Smet, PAGM. Herbs, health and healers: Africa as ethnopharmacological treasury. Berg en Dal: Afrika Museum, 1999.

- De Buck, J. Guérison: representation et guérison. (Bruxelles: Jo De Buck Tribal Arts, 2013).

- Goerdt, A, D Page, and PE Udo Umoh. Deformity Masks and their Role in African Cultures:the Ann Goerdt Collection. (Bayside: QCC Art Gallery Press, 2018).

- Hofmann, B. “Disease, illness, and sickness.” In: The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Medicine, M Solomon, JR Simon, and H Kincaid, eds. (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 2017): 16-26.

- Goerdt, A. “Influence of disease in African carving.” In: Deformity Masks and their Role in African Cultures: the Ann Goerdt Collection. (Bayside: QCC Art Gallery Press, 2018): 19-51.

- Cole, HM. “Disease or invention? Riffs on Beauty and the Beast.” In Deformity Masks and their Role in African Cultures: the Ann Goerdt Collection. (Bayside: QCC Art Gallery Press, 2018): 13-17.

- Imperato, PJ. “Book review: Deformity Masks and their Role in African Cultures.” J Community Health 44 (2019):626-627.

- Simmons, DC. “The depiction of gangosa on Efik-Ibibio masks.” Man 57 (1957):16-20.

- Ottenberg, S. “Psychological aspects of Igbo art.”African Arts 21, no. 2 (1988):72-82+93-94.

- Himmelheber, H. Negerkunst und Negerkünstler. (Braunschweig: Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1960).

- Ebong, IA. “The aesthetics of ugliness in Ibibio dramatic arts.” African Studies Review 38, no.3 (1995):43-59.

- Haaf, E, and J. Zwernemann. Geburt – Krankheit – Tod in der afrikanischen Kunst. (Stuttgart: F.K. Schattauer Verlag, 1975).

- Picton, J. “Ekpeye Masks and Masking.” African Arts 21, no.2 (1988):46-53+94.

- Vogelzang, J, P. Van den Hombergh, and J Bakkers. Images of power: krachten en beelden. (Amsterdam: Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen, 1997).

- Irobi, E. “Theatre of Images: the Mask as a Metalanguage in Indigenous African Drama.” S Afr Theatre J 19, no.1 (2005):223-241.

- Moreau, JL. “Mutilations bucco-faciales, maladies tropicales et masques d’Afrique.” Actual Odontostomatol (Paris) 142 (1983):341-356

- Mafart, B, G Thiery, and JC Dubosq. “Le noma: passé, present … et avenir?” Médecine Tropicale 62, no. 2 (2002):124-125.

- Marck, KW. Noma: the Face of Poverty. (Hannover: MIT-Verlag, 2003).

- Weinhold, U. Eternal Face: African Masks and Western Society. (Berg en Dal: Afrika Museum, 2000).

- Klever, U. Bruckmann’s Handbuch der afrikanischen Kunst. (München: Bruckmann, 1975).

- Adala, HS. “Ocular injuries in Africa.” Soc Sci Med 17 (1983):1729-1735.

- Ukponmwan, CU and N Momoh. “Incidence and Complications of Traditional Eye Medications in Nigeria in a Teaching Hospital.” Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 17 (2010):315-319.

- Sandford-Smith, JH and HC Whittle.”Corneal Ulceration Following Measles in Nigerian Children.” Br J Ophthalmol 63 (1979):720-724.

- Baiyeroju-Agbeja, AM and HA Ajibode. “Causes of removal of the eye in Ibadan.” Niger J Surg 3, no. 2 (1996):38-40.

- Shehata, MA, SA Abou-Zeid, and AF El-Arini. “Leprosy of the Nose: Clinical Reassessment.” Int J Lepr 42 (1974):436-445.

- Kim, JH, et al. “Analysis of Facial Deformities in Korean Leprosy.” Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 6, no. 2 (2013):78-81.

- Grzybowski, A, M Nita, and M Virmond. “Ocular leprosy.” Clin Dermatol 33 (2015):79-89.

- Fenton, WN. “Masked medicine societies of the Iroquois.” Annu Rep Board Regents Smithson Inst 1940 (1941): 397-429. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

PETER AGM DE SMET is a retired Dutch drug information pharmacist, clinical pharmacologist and emeritus professor of pharmaceutical care at the UMC Radboud Nijmegen. He is still active as ethnomedical and ethnopharmacological researcher.

Leave a Reply