Richard de Grijs

Sydney, Australia

Johnny Depp seems to have taken his role as Captain Jack Sparrow in the movie franchise Pirates of the Caribbean quite literally. His appearance at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival unleashed a minor scandal as fans’ complaints about his supposedly “rotting teeth” went viral.1 While Depp should be able to afford modern oral healthcare, during the Age of Sail, sailors—including pirates—often found themselves in less enviable circumstances.

The internet is awash with stereotypical images of pirates, often sporting black or rotting teeth, the occasional golden crown, and frequent instances of missing teeth. One could rightly blame scurvy as a major cause of sailors’ poor oral health in past centuries, but the root of the problem ran much deeper.

Scurvy, a disease caused by extreme Vitamin C deficiency, was rife on the long-haul oceanic voyages of the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries.2 Scurvy-induced tooth loss results from severely weakened, receding, or protruding gums: “It rotted all my gums, which gave out black and putrid blood”3—indeed, literally a foul “sailor’s mouth.” Sea surgeon William Clowes (ca. 1543/4–1604) offered an equally graphic diagnosis:

Their gums were rotted even to the very roots of their very teeth, and their cheeks hard and swollen, the teeth were loose near ready to fall out… their breath a filthy savor.4

Meanwhile, keeping other diseases at bay in the close confines of the crew quarters on merchant, privateering, and navy vessels alike pushed oral hygiene—brushing, flushing, and regular dental check-ups—a long way down the priority list. Cavities, oral bone loss, infections (specifically, gingivitis and periodontitis), and deterioration of dental anatomy were frequent afflictions. Often, sailors would only realize they had a serious cavity when a tooth started to hurt. By that time, however, tooth decay had already caused the enamel and the soft, fleshy dentin underneath to wear away, exposing the sensitive nerves in the tooth’s root pulp.

Perhaps unexpectedly, common shipboard diets contributed significantly to oral corrosion and, hence, to enhanced tooth decay.5 Once fresh fruit and vegetables had run out or had spoiled, daily provisions consisted mainly of hardtack (biscuits), dried and salted meats, beer and other alcoholic beverages (including wine, brandy, or grog), long-lasting dairy products such as hard cheeses, as well as stews made of anything caught or found en route, including birds, turtles, eggs, any type of seafood, and even snakes.

The Rev. Walter Colton (1797–1851), chaplain on board USS Congress, pointedly summarized the common sailor’s diet in the mid-nineteenth century:

He makes his meals from bread which the hammer can scarcely break, and from meat often as juiceless and dry as the bones which it feebly covers. The fresh products of the garden and the fruits of the field have all been left behind. As for a bowl of milk, which the child of the humblest cottager can bring to its lips, it is as much beyond his reach as the nectar which sparkled in the goblets of the fabled divinities on [Mount] Ida.6

Among the provisions sailors had routine access to, hardtack and beer were most frequently consumed, yet they also contributed most to oral acidity given their high carbohydrate (sugar) content. These sugars acted as fuel for the microbial populations in the mouth to produce acidic by-products, creating cavities and caries, particularly along the gum lines,7 and eventually causing lesions and abscesses8 and wreaking havoc on the mouth’s bone structure.

Although regular consumption of biscuits sped up the men’s tooth decay, the hardtack’s coarse and hard consistency and rough surface simultaneously acted as a teeth cleaning mechanism of sorts. The biscuits’ abrasive texture helped scrape off any built-up food residue, plaque, and tartar from the dental enamel, although it would also gradually polish off any remaining surface features on the men’s teeth, thus rendering them flat and poorly fitting together.9 In essence, the sailors’ regular hardtack consumption complemented their efforts (if any) at cleaning their teeth, for which they might have used “chew sticks” (frayed twigs) when available.

Chew sticks had been used by the ancient Babylonians and Egyptians as early as 3500–3000 BC,10 and they saw continued use well into the eighteenth century.11 (Boar-bristle toothbrushes were first introduced in China in 1498, although they did not reach Europe until the seventeenth century; development of the modern, nylon-bristled toothbrush—“Doctor West’s Miracle Toothbrush”—commenced in 1938.12,13)

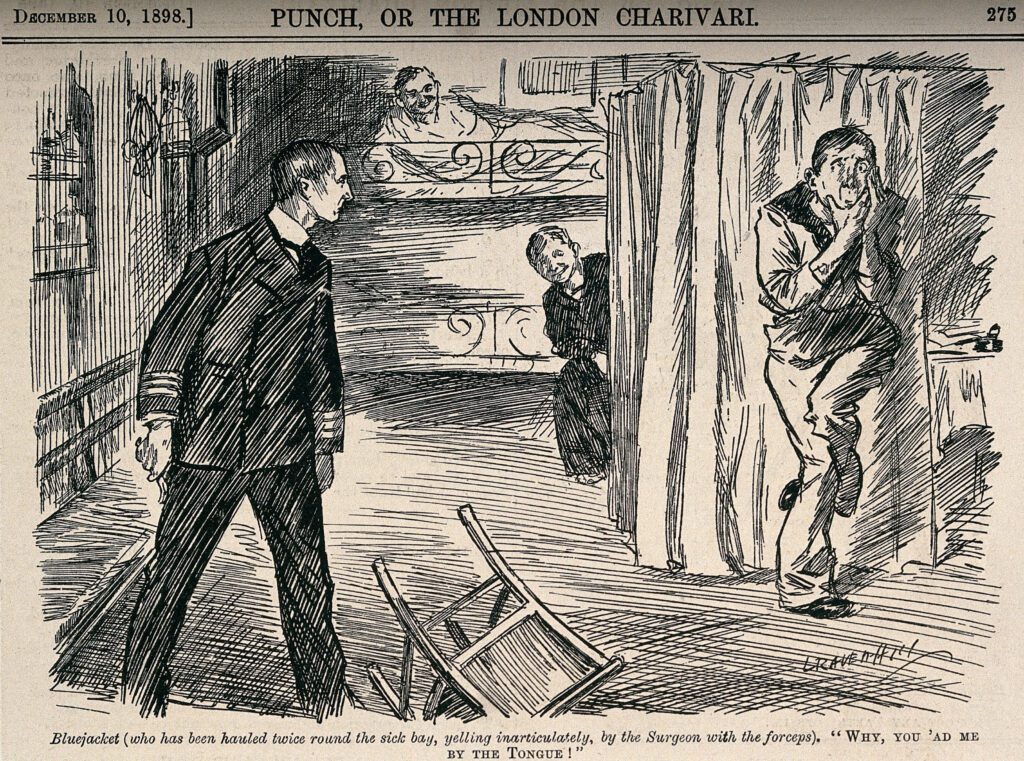

Given a severe lack of trained dental surgeons on board, for most of the Age of Sail toothaches routinely prompted dental extractions. Dental care had become a routine part of the sea surgeon’s remit:

His pole, with pewter basins hung,

Black, rotten teeth in order strung,

Rang’d cups that in the window stood,

Lin’d with red rags, to look like blood,

Did well his threefold trade explain,

Who shav’d, drew teeth, and breath’d a vein.14

In the absence of a qualified surgeon, the ship’s cook, boatswain, or master gunner would be expected to undertake any dentistry required. Until the 1790s, when nitrous oxide (“laughing gas”) was added to the dentist’s arsenal more frequently, dental care was undertaken without any application of local anesthesia—and often using tools that had not been disinfected properly. The American dentists Horace Wells (1815–1848) and William T.G. Morton (1819–1868) were the first to demonstrate the beneficial use of nitrous oxide for extractions in 1844, and of ether for surgeries in 1846. (Half a world away, the pre-Inca civilizations in Bolivia and Peru had already perfected the use of coca leaf-derived anesthesia to numb the gums and mouth for oral surgery, well over a thousand years earlier.)

In his seminal treatise The Surgion’s Mate (1617),15 John Woodall (1570–1643), Surgeon General to the East India Company, provides a detailed inventory of the surgeons’ chests on board the Company’s vessels. His descriptions cover a range of dental instruments—paces and “crowes bills” (forceps), “pullicans” (pelicans; precursors to modern forceps, resembling a pelican’s beak), forcers or punchers (elevators), “flegmes” (single-bladed phlebotomy instruments for opening veins or lancing gums), “grauers” (scalers), and small (bone) files—meanwhile explaining that:

… each of them are needful in the Surgeons chest, and cannot be well forborne for the drawing of teeth, as also the cleaning of the teeth and gummes, and the letting of the gums bloud are often no small things for keeping men in health at sea, and sometimes doe save the lives of men both at sea and land.16

In 1626, surgeons’ chests were issued free of charge to medical professionals who enlisted in the British Army.17 By the late eighteenth century, however, Royal Navy surgeons were required to procure their own inventory. Moreover, their chests were subject to inspection prior to embarkation by the Company of Surgeons, which was granted a royal charter in 1800 and renamed the Royal College of Surgeons in London. Royal Navy regulations of 1731 required that after examination and to prevent unauthorized sale or pawning of their medical instruments, chests had to be locked:

… and the seals of the Physician and of the Surgeons’ Company to be affixed thereto in such a manner, as to prevent its being afterwards opened, before it comes on board; nor is the Captain to admit any Chest into the Ship without these marks upon it.18

Among the prescribed instruments, a key tooth instrument (which replaced the older pelican), a gum lancet for draining gumboils and therapeutic bleeding within the mouth, two pairs of tooth forceps, and a punch formed the surgeon’s dentistry inventory.19 Dental keys were employed to force teeth out or even to break them into pieces.

Modern dentistry arguably has its roots in historical naval healthcare. Pierre Fauchard (1678–1761), the French surgeon credited as the Father of Modern Dentistry, wrote the first complete textbook of modern dentistry, Le Chirurgien Dentiste ou Traité des Dents (The Dentist Surgeon, a Treatise on Teeth; 1723). Importantly, he also identified that oral acidity induced by consuming carbohydrates resulted in tooth decay. Aged fifteen, Fauchard had enlisted in the French royal navy under the patronage of an expert in diseases of “dental organs.”20

Fauchard’s work marks the start of dentistry as a separate medical specialty. He built upon several earlier publications, including the Artzney Buchlein wider allerlei kranckeyten und gebrechen der Tzeen (The Little Medicinal Book for All Kinds of Diseases and Infirmities of the Teeth, 1530), published by Michael Blum (fl. 1525–1559) in Leipzig (Saxony, later part of Germany), the Collected Works (Paris, 1575) of Ambroise Paré (ca. 1510–1590), the Father of Surgery, and The Operator of the Teeth (New York, 1685/6) by Charles Allen.

In the US Navy, the first dedicated dental officer was appointed as early as 1873.21 In the Royal Navy, however, it took until the 1960s before ships’ designs incorporated dedicated dental surgeries—and even then, commanding officers were given the choice of “teeth or souls,”22 that is, to enlist a “toothwright” (“Toothie”) or a chaplain.

Naval dentistry has come a long way since the Age of Sail. Although the proverbial “sailor’s mouth” may never disappear, the term has become synonymous with the use of vulgar and profane language rather than reflecting tooth decay.

References

- Cox-Peralta, RA. “Fans Alarmed By Johnny Depp’s ‘Rotten’ Teeth At Cannes Film Festival, Compared To Capt. Jack Sparrow’s.” (May 21, 2023). https://www.imdb.com/news/ni64089245/.

- de Grijs, R. “Plague of the Sea, and the Spoyle of Mariners” – A brief history of fermented cabbage as antiscorbutic.” Hektoen International (2021). https://hekint.org/2021/06/17/plague-of-the-sea-and-the-spoyle-of-mariners-a-brief-history-of-fermented-cabbage-as-antiscorbutic/.

- Brown, SR. Scurvy How a Surgeon, a Mariner, and a Gentleman Solved the Greatest Medical Mystery of the Age of Sail. (Cheltenham: The History Press, 2003), 34; citing an unnamed 16th century sailor, possibly Antonio Pigafetta (1480–1531).

- Ibid., 34.

- Bishop, M. “So You’ve got a Sailors Mouth, Eh?” Institute of Nautical Archaeology (2020). https://nauticalarch.org/ship-biscuit-and-salted-beef/so-youve-got-a-sailors-mouth-eh/.

- Colton, W. Deck and Port; or, Incidents of a Cruise in the United States Frigate Congress to California. (New York: A.S. Barnes and Co., 1850), 43–44.

- Anderson, Q. “Dentistry and the British Army: 1661 to 1921.” British Dental Journal, 230 (2021): 407–416.

- Moore, WJ and Corbett, ME. “The distribution of dental caries in ancient British populations. III. The 17th century.” Caries Research, 9 (1975): 163–175.

- Bishop, Op. cit.

- Science Reference Section, Library of Congress. “Who Invented the Toothbrush and When was it Invented?” (2019). https://www.loc.gov/everyday-mysteries/technology/item/who-invented-the-toothbrush-and-when-was-it-invented/.

- Holmes, R. Redcoat, the British soldier in the age of horse and musket. (London: Harper Collins, 2001).

- Science Reference Section, Library of Congress, Op. cit.

- Colgate Global Scientific Communications. “The Ancient History of Toothbrushes and Toothpaste.” (2023). https://www.colgate.com/en-us/oral-health/brushing-and-flossing/history-of-toothbrushes-and-toothpastes.

- From The Goat without a Beard by John Gay (1685–1732). https://kalliope.org/en/text/gay2005052922.

- Woodall, J. The Surgions Mate, Or, a Treatise Discouering Faithfully and Plainely the Due Contents of the Surgions Chest. (London: Edward Griffin, 1617).

- Cited by Anderson, Op. cit.

- Anderson, Op. cit.

- Cited by Dobson, J. “Pernicious remedy of the naval surgeon.” Journal of the Royal Naval Medical Service, 43 (1957): 23–28.

- Goddard, JC. “The navy surgeon’s chest: surgical instruments of the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic War.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 97 (2004): 191–197.

- Verney, K. “Dentistry in Nelson’s time.” Journal of the Royal Naval Medical Service, 91 (2005): 96–98.

- Elliott Jr., RW. “Organization of the Navy Dental Corps.” International Dental Journal, 25 (1975): 266–275.

- Grant, EJ. The Toothwright’s Tale: A History of Dentistry in the Royal Navy 1964–1995. (Gosport, UK: Chaplin Books, 2012).

RICHARD DE GRIJS, PhD, is a professor of astrophysics and an award-winning historian of science at Macquarie University (Sydney, Australia). With a keen interest in the history of maritime navigation, Richard is a volunteer guide on Captain Cook’s (replica) H.M. Bark Endeavour at the Australian National Maritime Museum. He also regularly sails on the Museum’s replica Dutch East Indiaman, Duyfken.

Leave a Reply