Sally Metzler

Chicago, Illinois, United States

Few historical figures present singular profiles of good or evil. Often, the confluence of disparate actions molds the fame or infamy of great leaders. A prime example is Byzantine Emperor John Tzimisces (b. 925–d. 976). Though he rose to power through murder, he consistently displayed a marked benevolence towards the sick and poor.

On the snowy night of December 10, 969, in Constantinople, John and his retinue, aided by his mistress the Empress Theophano, murdered Emperor Nicephorus Phocas and immediately seized the reins of power. The Patriarch Polyeuctus, horrified at this act of violence against Christendom’s supreme basileus (deemed “equal of the Apostles”), insisted on penance before John would be allowed to enter the cathedral for his coronation on Christmas Day. The conditions of penance rested on the following: his mistress Theophano must be exiled, and his accomplices duly punished. Tzimisces complied, favoring the throne over his mistress.

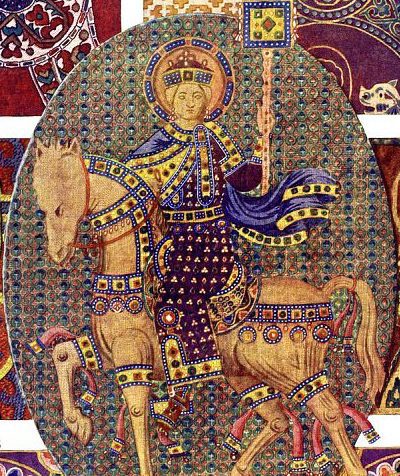

Once seated on the throne, John Tzimisces set to work and carved out a respectable and successful legacy. Known for his dashing demeanor and handsome visage, observers noted women found him irresistible in appearance as well as in conduct towards them.1 He garnered admiration for his archery skills and acumen in battle. Among his impressive military tactics was the feigned retreat, which he employed in the battle with the Russian Prince Svyatoslav at Drista. He also outmaneuvered and outsmarted Tsar Boris of Bulgaria, who abdicated, thus ending hegemony of the House of Krum. Bulgaria became under Tzimisces an imperial province. Now successful in the Balkans, he turned his sights east, conquering myriad territories: Emesa (current day Homs), Baalbek, Damascus, Palestine, Tiberias, Nazareth, Sidon, Beirut, and Byblos; an almost unending list of triumphs. Tripoli stood among the few that resisted the Byzantine assault and remained independent.

When not conquering territories or defending his position back home, Tzimisces found time to participate in charitable activities, thus mollifying his initial reputation for brutality when he usurped the throne through murder. Stemming from an aristocratic family,2 before he took office, he distributed much of his wealth to the poor, favoring farmers suffering from bad harvests. His favorite charity was the Leprosarium, or Nosocomium, a hospital across the Bosphorus that treated and housed lepers. Most impressively, he visited on a regular basis, “giving sympathy and encouragement to the patients and occasionally even bathing their sores with his own hands.”3 Notably, he treated lepers and the maimed with abundant generosity compared to other unfortunate souls.4

The practice of caring for lepers in Constantinople was by no means novel. Credit goes to St. Zotikus, who by the fourth to early fifth century established a leprosarium.5 He accompanied Emperor Constantine the Great when the emperor built his new, Eastern capital in Byzantium—Constantinople. He was horrified by the military practice of drowning lepers, and not only established a philanthropic facility and hospital for lepers, but also one for orphans. Through the centuries, the fortune of the Leprosarium waxed and waned. Emperor Maurice restored it (582–602), and it was later expanded by both Constantine VII and John Tzimicses.6

Interestingly, society judged patients suffering from leprosy in the Middle Ages and earlier with conflicting views: some considered them favored by God, pauperes Christi—”Christ’s special poor”—and others shunned them vehemently, deeming them sinners being punished by God.7 Nevertheless, leprosy patients evoked fear among the populace as concerns contagion, and the compassion towards them by Tzimisces merits admiration. A man who was said to have never known “a day’s illness until the end,”8 he succumbed to his death on January 10, 976. The details surrounding the cause remain shrouded in mystery. Perhaps diminished and worn by his ambitious foreign campaigns, or in fact the victim of a slow-acting poison surreptitiously added to his cup at dinner? A report reveals the morning after he dined with a “rich vassal in Bithynia”9 he was “…scarcely able to move his limbs, his eyes streaming with blood and his neck and shoulders covered with suppurating sores.”10 The Emperor reigned for only six years and one month. According to biographer John Julius Norwich, rather than a mysterious poison, John Tzimisces more likely left this world fighting a battle with typhoid, malaria, or dysentery.11

Thus, Emperor John Tzimisces distinguished himself as a supremely successful military and political ruler. Had his record not possessed the blemish of his murderous usurpation of the throne, posterity would recognize his reign as “a new paradise, from which flowed the four rivers of justice, wisdom, prudence and courage…had he not stained his hands with the murder of Nicephorus, he would have shone in the firmament like some incomparable star.”12

End notes

- Some sources use the spelling “Tzimiskes”. Three excellent discussions of the reign of John Tzimisces can be found in the following histories: The History of Leo the Deacon: Byzantine Military Expansion in the Tenth Century, by Leo Diaconus, with introduction, translation, and annotations by Alice-Mary Talbot and Denis F. Sullivan, Dumbarton Oaks Studies XLI, The History of Leo the Deacon, 2005 (hereafter Leo the Deacon); John Julius Norwich, Byzantium, Vol. II The Apogee (three vols total), Knopf, New York, 1995, chapter on Tzimisces pp. 211-230; and George Ostrogorsky, History of the Byzantine State, Rutgers Press, New Brunswick, NJ, revised edition 1969, pp. 293-298. Referenced henceforth as Norwich and Ostrogorsky.

- In fact, “he originated from a noble Armenian family (the nickname “Tzimiskes” is derived from Armenian “Chmishkik”, meaning “short stature.”) See: Art-A-Tsolum, All About Armenia, May 1, 2019, https://allinnet.info/antiquities/john-i-tzimiskes-byzantine-emperor/

- Norwich, p. 213. The Noscomium was located in Chrysopolis, referring to the modern-day suburb Üsküdar, near İstanbul, Turkey. For a complete history on leprosy in Byzantium, see Timothy S. Miller, John W. Nesbitt: Walking Corpses: Leprosy in Byzantium and the Medieval West, March 2014, Cornell University Press.

- Leo the Deacon, p. 220.

- St. Zotikos founded a leprosarium in the second half of the 4th c. outside the walls on a hill across the Golden Horn from Constantinople (in the region later termed Pera), at a location called Elaiones (“olive trees”). See T. Miller, “The Legend of St. Zotikos according to Constantine Akropolites,” AB 112 (1994): 339-76.

- See Marka Tomić, p. 24, “The cult of Saint Zotikos Orphanotrophos and his images in Byzantium and beyond,” Institute for Byzantine Studies, SASA, Belgrade, Serbia, digitized by the National library of Serbia.

- The punitive view of leprosy patients held to the “…Old Testament disease concepts proclaiming leprosy a divine punishment for sins, with links to other ‘unclean’ bodily secretions, including menstrual blood, and sexual taboos such as intercourse during menstruation…and others. Another view considered the disease as a gift of God and labeled its sufferers—pauperes Christi—Christ’s special poor. Included in this notion were a series of Scriptural passages wherein Christ healed lepers by touch because they professed faith in the new religion. Singled out for such miracles in the Scriptures of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, lepers came to be regarded as individuals who in spite of their perceived sinfulness were closer to God.” See p. 174 in:

- Risse, Guenter B., Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals, Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Norwich, p. 230.

- Norwich, p. 229. The vassal is unnamed.

- Norwich, p. 229. He was able to travel back to his palace in Constantinople.

- Norwich, p. 229.

- Norwich, p. 230.

SALLY METZLER chairs the Global COVID-19 Monument Commission.

Leave a Reply