Eric Will

United Kingdom

“Disillusion can become itself an illusion if we rest in it.”

— TS Eliot

Frank Maudsley Parsons (1915–1989) was an English pioneer of hemodialysis in the mid-1950s. His contribution is well known to nephrologists, but came at a personal cost in recognition that he expressed in his published journal affiliations.

Context

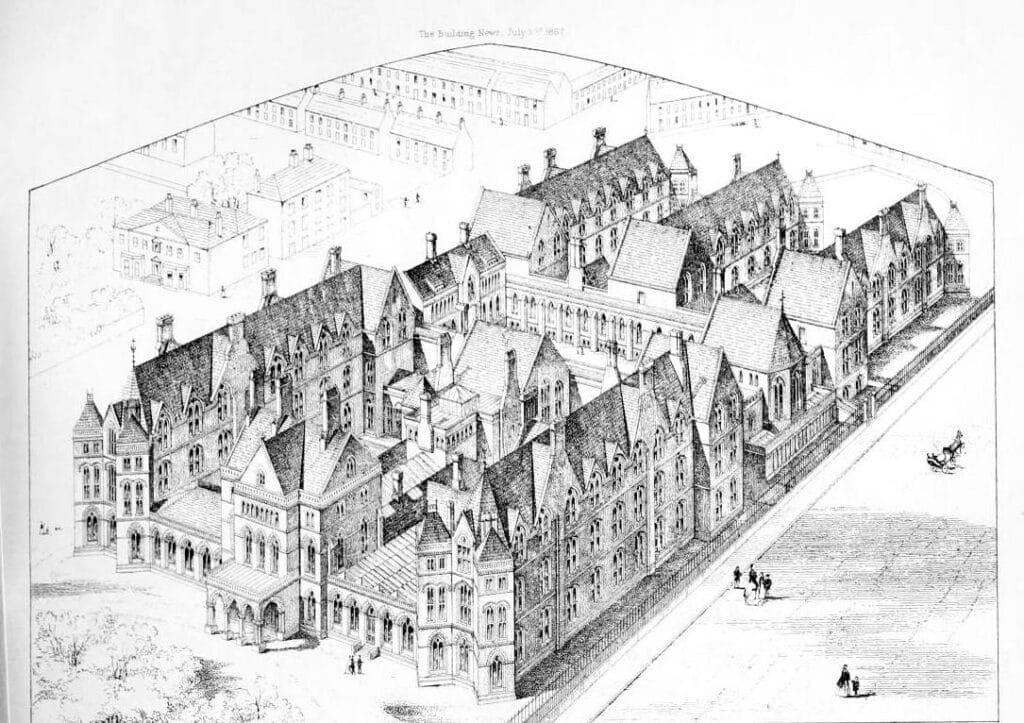

Leeds General Infirmary (LGI) was a long-established regional hospital that was incorporated in the UK National Health Service (NHS) after 1948. The institution was unusually conscious of its antecedents and reputation.1,2

Frank Parsons, a thirty-eight-year-old urology fellow visiting the department of John Merrill in Boston, had been exposed to the beginnings of modern hemodialysis (1953).3 He had an instinct for technical improvisation and was enthusiastic. With his patron Leslie Pyrah, the first UK professor of urology, through a combination of trust funds and national research monies, they purchased and set up a Kolff-Brigham rotating drum hemodialysis machine. The many subsequently referred cases were managed clinically within the academic department of medicine, whose staff provided a “lead physician.”4 They typically treated patients with what was hoped would be reversible acute renal failure.

This hybrid team was supported as a research exercise by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC), as part of unit funding conceded to the energetic Pyrah, named Honorary Director of the unit. For Parsons, the title of Assistant Director was preferred to Deputy Director, to head off an inevitable succession.

The Leeds General Infirmary

There were rewards for the LGI commitments. Its national reputation was enhanced by an early media presentation of the dialysis machine. The TV program Your Life in their Hands (1958) drew large audiences and publicity. Thereafter, Parsons was essentially a feather in the LGI hat, apparently courageous and a celebrity. A later media report of episodic renal transplantation further publicized LGI.

Because of subsequent NHS investment in Yorkshire, the significance of the renal program for the LGI soon became apparent. Their ambitious rebuilding plans of the early 1960s were not approved, ostensibly because of a need for greater medical student capacity in Leeds. Matters came to a head in the mid-1960s with the national decision to resource regional facilities for maintenance long-term hemodialysis. The Parsons effort was focused on acute provision and his equipment was not suitable for home treatment, the default maintenance dialysis option. He was not a naturally qualified candidate to run a regional program. Consequently, a formally trained nephrologist was appointed to both institutions in Leeds, to establish maintenance provision at St. James’s Hospital (SJH) (1966). Despite LGI maneuvers, renal transplantation was established subsequently at SJH, by which a renal program was consolidated but LGI discomforted. After Pyrah’s retirement and the MRC refashioning of their LGI investment (1964), Parsons fell out of the clinical renal mainstream as machines became available commercially. The diversion of patients by the SJH regional remit for renal replacement was hard to overcome and the renal program at LGI remained relatively modest despite the appointment of two nephrologists in the early 1980s. The reputation of the hospital was inevitably flattered by the partisanship that Parsons solicited, with a panegyric published by a Glaswegian renal transplant surgeon interested in medical history, his own medically published autobiographical valedictory, and papers by a contemporary torch bearer.3-6

Parsons’ progress

Parsons’ personal history within the UK kidney community of the early years was checkered. He looked for peer contact but was refused a forum in 1959 by the nephrophiles of the basic research-oriented national Renal Association (RA).7 He subsequently liaised with kidney replacement enthusiasts in Europe and became a regular contributor to the European Dialysis and Transplantation Association (EDTA), now the European Renal Association (ERA). It should be noted that only in 1968 would the RA accept other clinical dialysis enthusiasts.

Parsons’ more than fifty publications populated a wide variety of journals. It is through his declared author affiliations that we can trace his aspirations within the culture of the LGI. We can assume that was his covert intention. Having trained in urology, it was a problem to align his formal position with interdisciplinary clinical and research activity, especially when he showed a persistent interest in being named a Consultant. In 1961, the LGI itself appointed him Consultant in Clinical Renal Medicine, a unique local status. On Pyrah’s retirement, he was appointed as a locally defined Consultant in Clinical Renal Physiology (1963) to a renamed Renal Research and Urology program. Following honorary status by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (1961), he tended to drop the “Edin” suffix in affiliations and use FRCP (by implication the London College) and call himself Consultant Physician.8,9 In his BMJ swansong, accepted in 1988, he achieved the full apotheosis in print of FRCP, Consultant Renal Physician.6

Comment

The published affiliations show the personal efforts Parsons made to reconcile his training and practical pioneering efforts with the conventions of the medical hierarchy. The interdisciplinary work was not readily accommodated, a problem that persists today for progressive, unorthodox scientists. While he provoked the development of renal replacement medicine in modern nephrology and is now acknowledged as a “prophet in his own land,” the cost in personal frustration is written in a legacy of serial journal affiliations.

References

- Anning ST. The General Infirmary at Leeds. Volume 1. The first hundred years 1767-1869. 1963 E&S Livingstone Ltd. Edinburgh and London.

- Anning ST. The General Infirmary at Leeds. Volume II. The second hundred years 1869-1965. 1966 E&S Livingstone Ltd. Edinburgh and London.

- Turney JH. A disease and its device. The Introduction of Dialysis for Acute Renal Failure, with particular reference to Leeds, UK, c.1945 – c.2000. PhD thesis 2013

- Turney JH, Blagg CR, Pickstone JV. “Early dialysis in Britain: Leeds and beyond.” Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;57(3):508-515.

- Hamilton DH. “Developing the artificial kidney in Britain: Frank Maudsley Parsons at Leeds.” University of Leeds Review 1984; 27: 89–96.

- Parsons FM (FRCP, formerly Consultant Renal Physician) “Origins of haemodialysis in the United Kingdom.” Br Med J 1989;299:1557-1560.

- Cameron JS. The first half-century of the renal association, 1950-2000. 2000. UKKidney.org

- Heyburn PJ, Selby P, Peacock M, Sandler LR, Parsons FM (MD, FRCP, consultant physician). “Peritoneal dialysis in the management of severe hypercalcaemia.” Br Med J 1980;280(6213):525-526.

- Casson IF, Lee MR, Brownjohn AM, Parsons FM (FRCPE, Consultant Physician), Davison AM, Will EJ, Clayden AD. “Failure of renal dopamine response to salt loading in chronic renal disease.” Br Med J (Clin Res Ed)1983; 286(6364): 503–506.

ERIC JOHN WILL: After graduate research in the Netherlands on renal stone disease, the author was in clinical practice as a Teaching Hospital renal physician, 1980–2007. The renal department covered all adult nephrological disorders, including renal replacement by mixed maintenance dialysis and renal transplantation. Seven haemodialysis satellite units were established from the purpose-built main facility. Personal research included the analysis of clinical intention, medical decision support, and RCTs in renal anaemia. The author held national positions relating to clinical IT, being Secretary to the UK Renal Registry, 1997–2007.