Göran Wettrell

Lund, Sweden

Carolus Linnaeus, ennobled Carl von Linné in 1761, is one of the great sons of Sweden. At an early age, he demonstrated an interest in nature and plants. His lifelong passion was the ordering and classification of plants, animals, minerals, and diseases.

Young Linnaeus

Linnaeus was born in a small village in a southern province of Sweden in 1707 and was the first son in the family. His father, Nils Ingemansson, had changed his name when starting his studies in theology at the University of Lund, adopting the Latinate name Linnaeus after the linden tree growing at the family homestead. A clergyman interested in botany, he made sure that Carl was tutored at an early age in it and in Latin, but also experienced the beautiful woods and meadows surrounding their home. Nils also loved flowers and maintained a garden with many varieties of plants, some of them rare. According to Carl, his father’s garden “inflamed his soul with an unquenchable love of plants.”1

During his years in school at the cathedral town of Växjö, Linnaeus showed less interest in religion than he did in botany. One of his teachers, the regional doctor Johan Rothman, was impressed by Carl’s knowledge in botany and offered the gifted young man tuition for the study of both botany and medicine. Carl studied Boerhaave’s work in physiology and learned about the classification of plants by Tournefort, a French botanist.1

Studies at the University of Lund and of Uppsala

In August 1727, at the age of twenty-one, he entered Lund University.2 He had the good fortune to find a room at the house of Professor Kilian Stobeus, a natural scientist, collector, and physician. He was offered private tutoring in medicine, which included traveling with Stobeus during visits to patients in Scania (Skåne), the southernmost province of Sweden. Stobeus was impressed by Carl’s knowledge and motivation and allowed him to use his valuable and extensive library. He also was allowed to borrow books from the university library.

Stobeus had a private collection containing exclusive stones, shells, birds, and an herbarium. Carl learned much about minerals and started to collect flowers for his own herbarium. During the autumn of 1727 and spring of 1728, Linnaeus made several excursions in Scania and to the nearby gardens in Lund. He observed the flora, but also birds and insects, and documented eagerly in his college notebook. A year after he left Lund, he recorded a catalogue of the flora in Scania, Catalogues Plantarum rariorum Scaniae,1727–1728, which was later published.3 Some of his observations in Lund and Scania were also included in later publications.

In June 1728, he was probably bitten by a snake or hornet during an excursion, although the unknown organism was called Furia infernalis by Linnaeus. The bite became inflamed and formed an abscess in his arm, which required surgical treatment.2 He recovered in the home of his parents and met his former teacher, Doctor Rothman, who persuaded him to continue his studies in Uppsala. He wrote a letter to Stobeus, with whom he had developed a close relationship, and expressed his gratitude and indebtedness.

In September 1728, he arrived in Uppsala to continue his studies. He found, to his disappointment, that the famous botanical garden had been neglected. The two medical professors had grown old and had abandoned most of the medical teaching. Linnaeus studied by himself, using the medical and botanical books available at the university.1 Early in 1729, he visited Stockholm to attend a dissection and listen to lectures and demonstrations by doctors of the Collegium Medicum. Later that year, he met a new benefactor, Olof Celsius, a professor of theology, dean, and a devoted botanist. He and Linnaeus made several expeditions around Uppsala and meticulously documented the flora, which was later published in several dissertations and books.

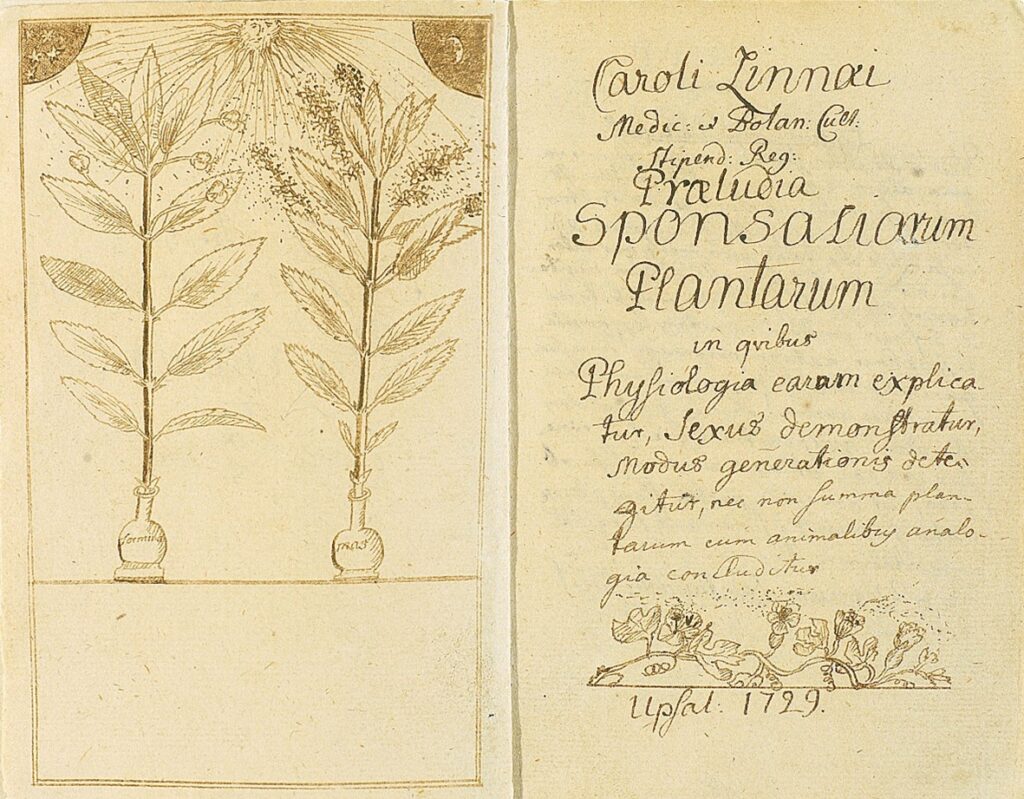

Celsius opened his home to Linnaeus and offered him the full use of his great botanical library. It was during this time that Linnaeus started to formulate his ideas about plant sexuality; how they were able to reproduce with stamens and pistils. These ideas were first announced in 1729 in a small botanical paper, Praeludia Sponsaliarum Plantarum, which was dedicated to Olof Celsius and later extended as a dissertation in 1746. A well-known medical professor, Olof Rudbeck the Younger, took notice of the paper on plant sexual reproduction and the impressive knowledge of Linnaeus. This led to Linnaeus being asked to give botanical lectures and arrange excursions in Uppsala. He addressed an increasing number of listeners, all fascinated by his vivid and unconventional personality.

The following years were filled with intensive work and many lectures in the field of botany, but also in zoology, geology, and dietetics for general health. With a modest grant from the Royal Society of Science in Sweden, Linnaeus successfully completed a journey to Lappland, a part of northern Sweden that was unexplored at that time. He recorded and collected information on the natural resources of the province.

In late 1734, he visited the town of Falun and its mine in the province of Dalecarlia. There he met his wife-to-be, Sara Lisa Moraeus, the daughter of a distinguished doctor employed at the mine. He realized that he would need a degree in medicine so that he could provide for a family. But his relationship with the physician Nils Rosén (ennobled von Rosenstein and seen as the father of Swedish medicine and modern pediatrics) hadalso worsened after Rosen´s arrival from Hardewijk with a medical degree. This set the stage for a competition for the future academic position of medical professor in Uppsala.1,4,5

Three years in the Netherlands

Linnaeus left Sweden by boat and arrived in Hardewijk, Netherlands in June 1735. He brought several manuscripts with him, and within a few weeks he had published and defended a paper for a medical degree. This first medical paper, entitled Hypothesis nova de februm intermittenticum causa, concluded that malarial fever arose from clay-rich soil and impure water, which led to moist, bad air.6

Linnaeus had planned to return to Sweden immediately because of a bad economy. However, he first wanted to visit Leiden. There he met Herman Boerhaave, who had been an important influence on his work. He also met Johan Frederik Gronovius, a famous botanist, and Johannes Burman, director of the Amsterdam Academic Garden. After Gronovius read Linnaeus’ notable manuscript Systema Naturae, he and some friends covered most of the cost of publishing it. It contained a classification of the three natural “kingdoms”: plants, animals, and minerals. The various plant species were for the first time arranged according to Linnaeus’ famous sexual system. The first edition, published in 1735, included only eleven printed folio pages.

Burman offered him work at the Amsterdam Botanical Garden and later facilitated the printing of Fundamenta Botanica (1736), in which Linnaeus proposed 365 aphorism-like rules of botany. Another important work, Genera Plantarum, was published the same year and dedicated to Boerhaave. In the fifth edition of this work, a complementary volume of Species Plantarum (1753) was added. Linnaeus’ sexual system of classification was used and the binomial nomenclature (genera and species) was established. Species Plantarum was regarded by Linnaeus himself as his “masterpiece” and the naturalist Albrecht von Haller described it as his maximus opus et aeternum.7

With Burman’s help, Linnaeus met the director of the East-India Company, George Clifford, who was also interested in botany. His estate at Hartekamp had a magnificent botanical garden, impressive herbarium, and outstanding botanical library. This was an excellent opportunity to continue his botanical work. Fourteen additional works were released during this period. The magnificent book Hortus Cliffortianus (1737) was compiled within a year. The book was printed in folio, with more than 400 pages and thirty-seven beautiful copperplate illustrations of the plants in the garden.

During the summer of 1736, Linnaeus visited England and met several well-known scientists, naturalists, and botanists, including Sir Hans Sloane, Professor J.J. Dillenius in Oxford, and gardener Philip Miller at the Chelsea Garden. He brought home to Hartekamp a collection of rare living plants. Beginning with his time in the Netherlands, he corresponded with many European natural scientists. His correspondence included more than one thousand letters, including a close and regular exchange with Albrecht von Haller, a botanist, physiologist, and professor in Göttingen. During the summer of 1738, after delaying his departure from the Netherlands and giving a sad farewell to the dying Boerhaave, Linnaeus went to Paris to visit Professor Bernard de Jussieu at the Royal Garden and the Academie des Sciences. He then left by boat from Rouen and returned to Sweden in June 1738.1,5

Practicing doctor in Stockholm and professor in Uppsala

After some initial difficulties, Linnaeus established himself as a doctor in Stockholm. He soon met influential people such as Lord Marshal and Count C.G. Tessin who arranged for Linnaeus to be a doctor to the Admiralty. During the spring of 1739, Linnaeus was also one of the founders and the first president of the Academy of Science in Stockholm. He could now marry his beloved Sara Lisa. In 1741, he completed a government-commissioned trip to the islands of Öland and Gotland. That same year, he was appointed to a professorship in practical medicine in Uppsala. But soon he changed positions with the other professor, Nils Rosén, and took responsibility for the botanical garden. He also lectured in botany, materia medica (plant and substances as medication), dietetics (general health advice), and semiotics (medical symptoms).

In the following years, he traveled to some national provinces, Västergötland (1746) and Scania (1749), to describe life and nature there. He was a good observer, always intending to see more in something very small, “maximus in minimis.” Linnaeus also sent his most gifted students, his “apostles” as he called them, on expeditions all over the globe to bring back plants, animals, and minerals. Two of his Swedish students joined James Cook on his circumnavigation of the world: Daniel Solander for the first voyage in 1768–1771, and Anders Sparrman on the second voyage, which included the Antarctic Circle. The number of “apostles” were about twenty, and one-third of them died from disease on their expeditions.1,8

Physician

Linnaeus had started his studies in medicine at the University of Lund but had focused mainly on botany and materia medica. After settling down in Stockholm in 1738, he was a practicing doctor for a few years until he was appointed professor in Uppsala.

Linnaeus’ medical opinions have been recorded in his enthusiastic lectures and the written notes of many students who attended them.8-11 His dissertations are another way to learn about his medical and scientific contributions. He was the chairman for 186 dissertations, mostly in Latin, and was considered the author of most of them. In the dissertations Exanthema viva (1757) and Mundus invisibilis (1767), Linnaeus suggested that contagious diseases are caused by living infectious agents (contagium vivum), each specific for their disease, the “germ theory of disease.”12 He was remarkably accurate about the agent that causes scabies (Ascaris scabiei). Linnaeus’ views on contemporary scientific problems, and of particular interest, “Exanthema viva,” were published immediately after the introduction of smallpox inoculation into Sweden. The dissertations also included general health advice about food, restriction of alcoholic intake, clean air, daily physical activity, good sleeping habits, and support for breastfeeding. All his dissertations from 1749–1769 were collected and published in a work entitled Amoenitates academicae, “the academic pleasures.”

Linnaeus only published two short and systematic works in the field of medicine, Genera Morborum (1759) and Clavus Medicinae duplex (1766). During his stay in the Netherlands he read about the classification system of diseases, “Nouvelles classes de maladies” by Francois Baissier Sauvages de Lacroix. After that, Linnaeus started to construct an improved nosology in accordance with his system of botany. He corresponded for many years with Professor Sauvages at the University of Montpellier concerning classification, as well as practical medical questions. The early draft of a system of disease classification was found in his handwritten pocket notebook and entitled Vademecum. Linnaeus’ classification, a revision of Sauvages’ system, was published as a doctor´s thesis, Genera Morborum (1759). A further edition of this work was published in 1763. Linnaeus built his classification on symptoms and manifestations of disease, and less on speculative ideas about cause. The main groups to use this taxonomy were Swedish medical students and clergymen. The latter were responsible for delivering statistical reports on local diseases and cause of death.

Linnaeus’ main contribution to Sauvages’ extended classification was his use of binomial nomenclature and suggestions of plants for therapeutic use. His extensive knowledge of plants with healing properties (pharmacodynamics) was collected in his work Materia medica in 1749. It was presented on 250 pages and included more than 500 plants and their uses in more than 300 diseases. It formed the basis for a new Pharmacopoea Svecia published in 1775.1,5,8,10

At the time, medical theories were iatro-mechanical as proposed by Boerhaave, and focused on a state of equilibrium for the wellbeing of the body. Concerning diseases and their treatments, Linnaeus adhered to the maxim “Contruria contrariis curantur.”8 Published in 1766, his odd and short work about “the key to medicine,” Clavus medicinae duplex, was difficult to understand. He posited that all living creatures originate from two substances: the outer cortex, which was “male” and included bones, muscles, blood, viscera, and marrow, and the “female” inner substance, which was the source of the nervous system.

The medicinal plants which cured diseases in the cortex/marrow system, were based on their taste and smell. Carl Linnaeus, a hardworking naturalist with curiosity, creativity, and enthusiasm, exerted a great influence on the fields of botany and natural history. He is regarded as the founder of modern taxonomy by his use of binomial nomenclature. His scientific achievements are preserved in many places worldwide, such as the illustrious Linnean Society of London. At the bottom of his coat of arms is a phrase in Latin: “Famam extendere factis”—“We extend our fame by our deeds.”

References

- Uggla, A.HJ. Linnaeus. Swedish Institute, Stockholm (in English). Almquist och Wicksells boktryckeri. Uppsala, 1957: 3-16.

- Strandell, B. Linné i Lund (summary in English). Sydsvenska Medicinhistoriska Sällskapets Årsskrift, 1966: 81-102.

- Linné, C von. Catalogus Plantarum rariorum Scaniae. Carl von Linne´s ungdomsskrifter. Ed. F. Ährling. Stockholm, 1888:27-52.

- Bäck, A. Åminnelsetal över välborne Herr Carl von Linné. Kongl. Vetenskaps academien. Joh. Georg Lange. Stockholm, 1779.

- Carl Linnaeus. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.ora/wiki/ Carl Linnaeus. Accessed 25 December 2023.

- Hjelt, O.E.A. Carl von Linné som läkare. Finska Litteratur – Sällskapets tryckeri. Helsingfors. 1877: 89-91.

- Malmeström, E. och Uggla, A. HJ. Vita Caroli Linnaei. Carl von Linnés självbiografier. Almquist och Wicksell. Stockholm, 1957: 141, 164.

- Broberg, G. Mannen som ordnade naturen. En biografi över Carl von Linné. Natur och Kultur. Stockholm, 2019.

- Landell, N.E. Läkaren Linné. Medicinens dubbla nyckel. Carlssons. Stockholm, 2004.

- Hjelt, O.E.A. Carl von Linnés betydelse som läkare och medicinsk författare. Almquist och Wicksell. Uppsala, 1907.

- Perman, E. Carl Linnaeus- Botanist and physician. Physicians of Note. Hektoen International 6, no. 1, Winter 2014.

- De Lacy, M E. A Linnean Thesis concerning Contagium Vivum: The “Exanthemata viva” of John Nylander and its Place in Contemperary Thought. Medical History 1995;39:159-185.

GÖRAN WETTRELL, MD, PhD, FLS, is an associate professor and senior consultant in pediatric cardiology and pediatrics at Lund University, Sweden with a focus on pediatric pharmacology, cardiac molecular genetics, and primary arrhythmias. Other interests include male choir singing and medical humanities.

Leave a Reply