James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, United States

At a critical moment in the second act of Terrance Blanchard’s opera Champion, based on the life of the boxer Emile Alphonse Griffith, Emile’s trainer Howie Albert asks the fighter, whose boxing career is in a steep decline, if he can remember a sequence of three simple words: “school, bell and ring.” He also asks Emile to set the hands of a watch to ten minutes past eleven. When Emile can’t remember the words or how to set the time, Howie tells him: “It’s time to stop now, Emile.”1 Emile Alphonse Griffith was born in the U.S. Virgin Islands in 1938 and held world champion titles in three weight divisions. He died in 2013 at the age of seventy-five in a chronic care facility in Hempstead, NY, suffering from dementia pugilistica. The opera depicts his rise to fame and the controversial fight in Madison Square Garden on March 24, 1962, when he defeated the Cuban champion Benny “Kid” Paret with a violent series of knockout punches that put his opponent into a coma and led to his death ten days later. Through the fog of dementia, Griffith, haunted by Paret’s death, seeks forgiveness.

While Griffith’s quest for redemption is the larger theme of Champion, the neurologic complications of repeated head trauma associated with boxing underlies the story of the opera. First is the death of Paret from a subdural hemorrhage, the result of violent rotational acceleration of the brain from repeated blows to the head leading to the rupture of intracranial venous structures. A survey of boxing deaths reported in The Physician and Sportsmedicine occurring among amateur and professional boxers worldwide covering a 35-year period from 1945 to 1979 identified 335 fatalities.2 This period is concurrent with the date of the notorious bout between Griffith and Paret. The fatality rate for boxing has been calculated at 0.13 deaths per 1,000 participants.3 The second neurologic complication of boxing depicted in the opera is dementia pugilistica. Emile’s struggle with dementia bookends the opera from the first act to the spiritual final scene when he is finally able to resolve his guilt for having caused the death of Paret.

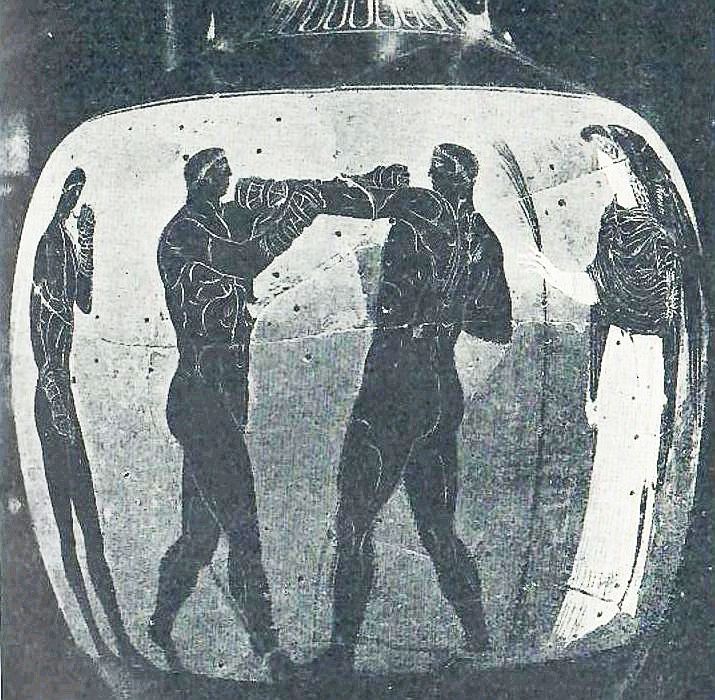

The origin of pugilism (boxing or fist fighting) is lost in prehistory. The first visual evidence can be found in the third millennium BC on monuments from Egypt and Mesopotamia. The sport was practiced in ancient India and introduced in 688 BC at the Olympiad in Greece. Pugilism disappeared from the historic record after the fall of the Roman Empire. Prizefighting made a reappearance in England during the 17th and 18th centuries when the term “boxing” came into common parlance. Concern for the welfare of the combatants received little attention though the Boughton Rules of 1743, and the Marquess of Queensberry rules of 1867 included measures aimed at standardizing the conduct and fairness of the fight.

An article, “Punch Drunk,” in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in 1928 by New Jersey pathologist Harrison Martland4 is cited as the first attempt by the medical profession to address the long-term neurologic sequelae associated with boxing. Martland described clinical features and natural history of the “punch drunk” syndrome. He called attention to a “staggering, propulsive gait with facial characteristics of the parkinsonian syndrome, or a backward swaying of the body, tremors, vertigo and deafness. Finally, marked mental deterioration may set in necessitating commitment to an asylum.” He believed that over half the fighters who continued to fight long enough develop a progressive form of this condition. His report includes the case of a 38-year-old fighter who began boxing in 1906 at the age of 16 and stopped fighting at the age of 23 in 1913 because of a tremor in his left hand and unsteadiness in his legs. Over the ensuing 15 years the boxer developed “a well-marked case of paralysis agitans [parkinsonian syndrome].” No pathologic material from boxers who had succumbed to this syndrome was available to the author, but he extrapolated from cases of traumatic head injury that he had observed personally or had been published and speculated that concussive hemorrhages lead to “gliosis” and degenerative neural changes. JA Millspaugh, a lieutenant in the US Naval Medical Corps, introduced the diagnosis “dementia pugilistica” as the term preferred to the colloquial “punch drunk” characterization.5

In the five decades since Harrison Martland’s paper appeared in JAMA, scattered reports in the medical literature have documented the clinical features of dementia pugilistica as well as small series of post-mortem neuropathologic studies of ex-boxers. The epidemiology of dementia pugilistica was reported by Anthony Herber Roberts6 in 1969 on 224 boxers with progressive memory loss, aggression, confusion, and depression out of 16,731 professional fighters registered with the British Boxing Board of Control from 1929 to 1955. The study indicated that 17% of those who had boxed for six to nine years displayed brain damage and one third showed signs of the “punch drunk” syndrome. The severity of their symptoms correlated with the number of fights and the length of the boxer’s career. In the same year, John Johnson of the Manchester Royal Infirmary published a survey of “organic psychosyndromes” in 17 ex-boxers who were carefully studied both from a neurologic and psychiatric standpoint. He identified the presence of five main psychiatric clinical syndromes: a chronic amnesic state, dementia, a morbid jealousy syndrome, rage reactions, and psychosis.7

Roberts pointed out that “the nature, and even the existence, of structural changes can be confirmed only by examining the brains as well as the lives of men known to have boxed.” It took 16 years for the authors of one study, “The Aftermath of Boxing,” to assemble a series of 15 ex-boxers documenting the clinical history and neuropathologic findings studied at the Runwell Hospital, Wexford, Essex.8 In this study, Corsellis and colleagues found gross pathological changes, including a reduction in brain weight, enlargement of the cerebral ventricles, and thinning of the corpus callosum. Histopathology revealed cell loss in the substantia nigra and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) similar to that of Alzheimer’s disease that were universal. A follow up study demonstrated diffuse amyloid plaques in the cerebral cortex of 14 of the patients in the original series and in the brains of six additional boxers.9

In 1996, a notable case report documented the neuropathology of a young 23-year-old boxer who died in the ring of a subdural hemorrhage. He began amateur boxing at the age of 11 years and boxed professionally for four years, participating in 19 fights. He had only been knocked out once in his boxing career. The principal histopathologic change was the presence of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) found throughout all layers of the cerebral cortex in close association with blood vessels. The authors note that NFTs are not found in neurologically normal subjects dying in the third decade of life, and the distribution of NFTs was different from the sites affected in early Alzheimer’s disease.10

These pathologic changes are characteristic of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a term coined by Henry Miller of the Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne, in a paper on the after-effects of head injury.11 Over 28 synonymic terms for CTE can be found in the literature.12 It is defined as a progressive neurodegenerative syndrome believed to be caused by single, episodic, or repetitive head trauma to the brain.13 Boxing is the most frequent sport associated with CTE.14 Boxers with long-standing CTE frequently develop dementia and may be misdiagnosed clinically with Alzheimer’s disease. In 1957, neurologist Macdonald Critchley of King’s College Hospital noted: “once established, it not only does not permit reversibility, but ordinarily advances steadily, even though the boxer has retired from the ring.”15

Throughout the twentieth century, CTE was considered to be primarily a disease of boxers. With the publication of back-to-back papers in the journal Neurosurgery by Bennet I. Omalu and colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh in 2005 and 2006, medical and public awareness of CTE took a dramatic turn.16 Each paper was a case study of a National Football League (NFL) player along with detailed neuropathologic findings consistent with CTE. Both players developed disturbing neuropsychiatric symptoms appearing in the years after their retirement from football. The primary author, Bennet Ifeakandu Omalu, was a little-known forensic pathologist working for the Allegheny County coroner’s office in Pittsburgh. He was born in 1968 in Nigeria and received his medical training at the University of Nigeria. In 1994, he immigrated to the United States and completed a fellowship in epidemiology at the University of Washington and a residency in anatomic and clinical pathology at Columbia University’s Harlem Hospital Center.

The first case report was that of Mike Webster, a Hall of Fame player for the Pittsburgh Steelers, who died in 2002 at the age of 50 after years of cognitive decline, drug abuse, and multiple suicide attempts. The second NFL player, Terry Long, suffered from depression and died by suicide at the age of 45. Both papers documented extensive neuropathologic changes attributed to repeated traumatic brain injury. The NFL’s committee on mild traumatic brain injury attempted to pressure the journal to retract the paper and discredit the findings. Omalu also found evidence of CTE in the brains three further NFL players who died under age of 50. The story of Omalu’s study of CTE and the opposition of the NFL are the subjects of Concussion, a book by Jeanne Marie Laskas and a film of the same name that appeared in 2015.

Given the prominence of football as a national sport in America, the publication of these two reports generated intense interest in the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and neuropathology of CTE. The findings of a national brain bank at the Boston University School of Medicine, published in JAMA in 2017,17 using carefully developed pathologic criteria, found CTE in 177 of 202 (87%) former football players. The severity of the neuropathology correlated with the highest level of play as found in professional athletes. Recent updates18 released by the Boston University CTE Center found in 345 of 376 former NFL players (91.7%). CTE has been reported in a variety of contact sports, including soccer and rugby, and also found in a military environment associated with concussion and head injury.

Currently CTE is a diagnosis that can only be established at post-mortem by neuropathologic examination of the brain. Histologically, there is a characteristic pattern of helical filaments of tau accumulation surrounding small vessels in the depths of the cortical convolutions of the brain. Tau is an abbreviation for the microtubular protein tau (MAPT) present in the normal human brain. Tau stabilizes microtubules that transport proteins from one neuron to another. Current thinking suggests that when tau becomes hyperphosphorylated it aggregates into neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) leading to impaired neural function. In CTE the pattern of tau deposition in CTE appears to be different from that seen in Alzheimer’s disease. Because there is a considerable latency between repetitive head trauma and the appearance of symptoms, there is an urgency to identify individuals at risk for CTE before the disease becomes clinically apparent. An example of this research, a study combining a tau specific ligand with positron emission tomography (PET), looked at 26 former NFL players with cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms comparing them with 31 normal controls.19 The NFL players had higher levels of tau found on scanning, but a correlation between the degree of tau deposition and neuropsychological impairment could not be established. The problem of early diagnosis remains to be resolved.

Of the contact sports, boxing is the only one where the goal of the contest is to render one’s opponent “injured, defenseless, incapacitated or unconscious.” Between 1980 and 2007, 200 amateur and professional fighters have died of injuries in the ring. In 1983, the editor of JAMA, Dr. George Lundberg, deemed boxing an “obscenity” and a “throwback to uncivilized man . . . not to be sanctioned in a civilized society.”20 The medical associations of Britain, Canada, and Australia have called for the ban of boxing. National bans on boxing exist in Iceland, Iran, and North Korea, and the sport has been intermittently banned in Sweden and Norway. The concussion rate in boxing is highest of all contact sports, and the neurologic sequelae and CTE are more severe in boxing. The Lancet in 1982 published an article titled “Is Chronic Brain Damage in Boxing a Hazard of the Past?” The authors from the neurology, neurosurgical, and radiological departments of the University of Helsinki studied 14 boxers who had been Finnish, Scandinavian, or European champions.21 Twelve had clinical evidence suggesting chronic brain injury. The authors concluded that the then current measures aimed at ensuring the safety of boxing created a dangerous illusion, concluding: “The only way to prevent brain injuries is to disqualify blows to the head.” A casual search of the internet in 2024 reveals the following: the professional boxing industry in the United States in 2021 was worth $687 million, world wide boxing in 2020 was viewed by 123 million people, and the global boxing equipment industry generates the equivalent of $1.6 billion US dollars. While there is a place for the benefits derived from scientific boxing: training regimens, form, and fitness, given these statistics, a ban on head blows in competitive boxing is not likely, and the 20% of professional boxers who develop symptoms of chronic traumatic brain injury will pay the price for our entertainment.

References

- Champion: An Opera in Jazz. Music by Terrance Blanchard and libretto by Michael Cristofer. Final libretto revision, April 11, 2023, kindly provided to the author by Lyric Opera of Chicago.

- Moore, M. The Challenge of Boxing: Bringing Safety into the Ring. The Physicians and Sportsmedicine 1980;8:101-5.

- Council on Scientific Affairs. Brain Injury in Boxing. JAMA 1983;249(2):254-7.

- Martland, H. Punch Drunk. JAMA 1928;91(11):1103-7.

- Millepaugh, JA, Dementia Pugilistica. United States Naval Medical Bulletin. 1937;35:297-303.

- Roberts, AH. Brain Damage in Boxers. London: Pitman Medical Scientific Publishing Co, 1969.

- Johnson, J. Organic Psychosyndrome Due to Boxing. Brit. J. Psychiatry 1969;115:45-53.

- Corsellis, JAN, et al. The Aftermath of Boxing. Psychol Med. 1937; 3:270-303.

- Roberts, GW. The Occult aftermath of Boxing. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1990;53:373-8.

- Geddes, JF, et. al. Neurofibrillary Tangles, but Not Alzheimer-Type Pathology, in a Young Boxer. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology 1996;22:12-6.

- Miller, H. Mental After-Effects of Head Injury. Proc. Royal Soc. Of Medicine 1996;59:257-61.

- Omalu, B. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Prog Neurolog. Surg. 2014:28:38-49.

- Conidi, FX. Understanding the Cumulative Effects of Concussion. Practical Neurology, May 2015.

- McKee, AC, et al. Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Athletes: Progressive Tauopathy After Repetitive Head Injury. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. July 2009;68:709-35.

- Critchley, M. Medical Aspects of Boxing, Particularly from a Neurological Standpoint. British Medical Journal February 1957;1:357-62. Quoted in AC McKee et. al.

- Omalu, BI, et al, Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in a National Football League Player, Neurosurgery July 2005;57(1):128-34, and Omalu, BI, et. al, Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in a National Football League Player: Part II, Neurosurgery, November 2006;59(5):1086-93.

- Mez, J, et al. Clinicopathological Evaluation of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Players of American Football. JAMA 2017;318(4):360-70.

- Most, D, BU Finds CTE in Nearly 92 Percent of Ex-NFL Players Studied, The Brink February 7, 2023, https://www.bu.edu/articles/2023/bu-finds-cte-in-nearly-92-percent-of-former-nfl-players-studied/ and Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, Researchers Find CTE in 345 of 376 Former NFL Players Studied, https://www.bumc.bu.edu/camed/2023/02/06/researchers-find-cte-in-345-of-376-former-nfl-players-studied/.

- Stern, RA, et al. Tau Positron-Emission Tomography in Former National Football League Players. N Eng J Med May 2019;380(18):1716-25.

- Lundberg, GD. JAMA January 14, 1983;249(2):250.

- Kaste, M, et al. Is Chronic Brain Damage in Boxing a Hazard of the Past? The Lancet. Nov. 27, 1982;2:1186-1188.

JAMES L. FRANKLIN is a gastroenterologist and associate professor emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He also serves on the editorial board of Hektoen International and as the president of Hektoen’s Society of Medical History & Humanities.

Leave a Reply