Philip Liebson

Chicago, Illinois, United States

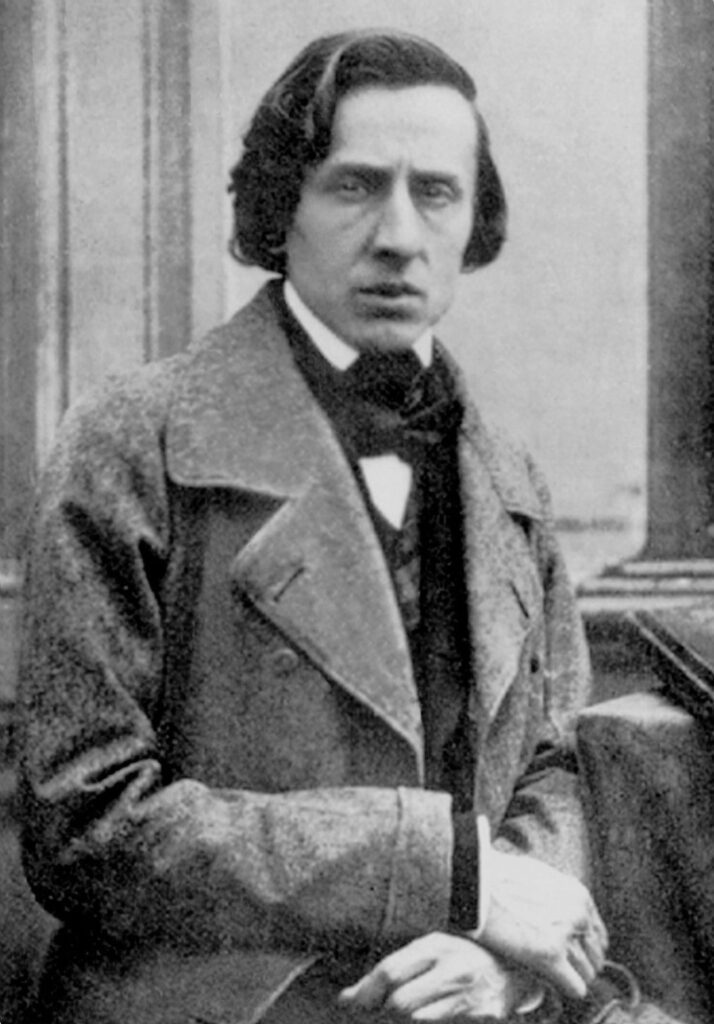

Frederic Chopin, remembered for his brilliant piano works, suffered from a chronic illness leading to a short life of only thirty-nine years. Yet he lived longer than Mozart, Schubert, Mendelssohn, or George Gershwin. Born in a suburb of Warsaw, he was sickly even as a youth and appeared on the verge of death in his early thirties. As he frequently coughed up blood, he was thought to have consumption, his age’s term for tuberculosis. Although some of his physicians thought that tuberculosis led to his death, this has not been definitively proven.

As a child, Chopin suffered from food intolerance, with diarrhea and weight loss. In adulthood, his weight was frequently below 100 pounds (he was five feet, seven inches in height). At sixteen he developed enlarged cervical lymph nodes and headaches. At twenty he cancelled concerts because of a prolonged cold. At twenty-one he coughed up blood for the first time. If that had been his first indication of tuberculosis, it would have been at least eighteen years before it killed him, unusual for the untreated disease. In his mid-thirties he developed severe laryngitis and bronchitis. In his last year of life, he had severe diarrhea.

Ten years before his death, he was in Majorca, where he suffered from cough and fever, and his doctors considered that he had tuberculosis. The local population avoided him because of the fear of that illness.

After his death in Paris, where he had lived for almost twenty years, one of his physicians, Jean Cruveilhier, performed an autopsy; the results of this were later destroyed. The death certificate, not the absent autopsy results, indicated death from tuberculosis of the larynx and lungs. Yet it was suggested at the time that the autopsy had not confirmed tubercular pulmonary changes. Cruveilhier himself told a friend of Chopin that the lungs did not indicate the cause of death and it may have been a disease that he had not seen before. It should be noted that Cruveilhier was the Professor of Pathology at the University of Paris and possibly the most recognized pathologist at that time.

Over the course of his life, Chopin had as many as fifty physicians across Warsaw, Paris, and London. Chopin’s father, who lived to seventy-three, had several respiratory infections. One sister died at forty-seven and also had recurrent respiratory infection. Another sister had cough, dyspnea, and recurrent upper gastrointestinal hemorrhages, dying from a massive bleed at age fourteen.

At his request, Chopin’s heart was preserved, but it was never examined histologically. However, in 2014, a visual inspection of Chopin’s well-preserved heart its container suggested that pericarditis had been present, which could have resulted from tuberculosis. Other diagnoses later entertained included alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and cystic fibrosis, neither of which were known as disease entities at the time.

Chopin’s clinical condition prevented him from giving concerts in any location except for small salons, yet most of his adult life he remained prolific in his production of etudes, nocturnes, waltzes, mazurkas, and polonaises. Although he requested that many of his works be destroyed after his death, they were fortunately preserved. George Sand, his companion, even recovered a manuscript from the fire while they were in Majorca.

References

- Lagerberg, S. Chopin’s Heart: The quest to identify the mysterious illness of the world’s most beloved composer. S. Lagerberg, 2011. ISBN 1-4564-0296-X.

- O’Shea JG. Was Frederic Chopin’s illness actually cystic fibrosis? The Medical Journal of Australia 1987;147:586-9.

- Cheng TO. Chopin’s Illness. Chest 1998; 114: 654-5.

- Carter ER. Chopin’s Malady. Chest 1998; 114: 655-6.

- Walker A. Fryderyk Chopin: A Life and Times. Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, New York: 2018.

PHILIP R. LIEBSON, MD, graduated from Columbia University and the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center. He received his cardiology training at Bellevue Hospital, New York and the New York Hospital Cornell Medical Center, where he also served as faculty for several years. A professor of medicine and preventive medicine, he has been on the faculty of Rush Medical College and Rush University Medical Center since 1972 and holds the McMullan-Eybel Chair of Excellence in Clinical Cardiology.

Leave a Reply