Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

“Think for yourself is the mantra she whispers in children’s ears. Don’t believe the teachers, the police, the child welfare workers…”1

– A resumé of Pippi Longstocking’s philosophy

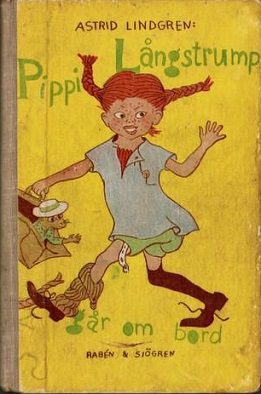

Pippi Longstocking (or Pippi Långstrump in the original Swedish) is a fictional nine-year-old girl. She has great self-confidence, superhuman strength, and much joie de vivre. She is the heroine of eight books by Astrid Lindgren (1907–2002), who wrote nearly 100 books, most of them for children. One-hundred-sixty-seven million of Lindgren’s books have been sold worldwide and translated into a hundred languages. Her active opposition to physical punishment of children spurred Sweden to pass the world’s first national law outlawing child corporal punishment in 1979, which became known as the Lex Lindgren.2,3

In the story introducing Pippi Longstocking, we read of a girl moving into an empty house next door to the children Tommy and Annika, and their mother. Pippi is carrying a horse by herself. She has a valise full of gold coins and lives with her horse and her monkey. Her mother has died and her sea captain father has been lost at sea. Pippi has no one who tells her when to go to bed, and “she always does exactly as she wishes.” She makes 500 cookies at a time, and washes the kitchen floor by skating on it with brushes attached to her feet. When she goes to a circus for the first time, she walks the tightrope, rides a horse while standing on its back, and wrestles and defeats the strongman, Mighty Adolf. When robbers come to her house, she captures them, and then gives them money to buy food. At her birthday party, she gives gifts to the guests.4,5

The first story about the girl who will not “conform to social expectations” appeared in 1945 in Swedish. She has “boundless energy” and no desire to adopt “good manners.” She does not go to school. Pippi is non-violent despite her enormous strength, and she interrupts bullying whenever she encounters it.6

In the 1940s and 1950s, there was a “reversion to circumscribed gender roles” and children were expected to be docile and submissive.7 Pippi was seen as a “liberating force for children who did not have the freedom she has,”8 enacting a “good-natured protest against the tyrannies of convention.”9 In a recent survey, Pippi was among the twenty-five book characters readers had “wanted to be as a kid.”10 She has also been called “the reason Sweden has more female members of parliament than anywhere other than Rwanda.”11

The first Pippi novel quickly became popular in Sweden. By the end of the 1940s, 300,000 copies had been sold (in a population of seven million Swedes). The stories were read on the radio, and a touring company performed a Pippi Långstrump play in several Swedish cities.12 The Swedes were not uniformly enamored of Pippi, nor of her author. In 1946, psychologist John Landquist wrote in a newspaper editorial that Pippi was an “unnatural girl” who was “mentally disturbed,” having “tasteless adventures.” Landquist was pro-Nazi before, during, and after the Second World War. Other commentators also called her “unnatural” and wrote about her “harmful behavior.”13,4

After Pippi was translated into English in 1950, her behavior was not seen as a problem by American reviewers, and a British critic wrote that “she appears to be the longing, the secret psychic demands of girls and boys.” She was also called “a perfect fantasy heroine—one who lives without supervision but with endless money to execute her schemes.”15 Five million copies of Pippi Longstocking had been sold in English by the year 2000. A television drama featuring Pippi was aired in Sweden in 1969. The film showed her as a “bohemian girl reminiscent of Swedish hippies,” and a “lovely eccentric.”16 Elsewhere she has been described as “a hippie before the 1968 movement.”17

Pippi Långstrump had less success when she arrived in France, where she became Fifi Brindacier (“Fifi strand of steel”). After the defeat of France and its occupation by Nazi Germany, the post-war rulers of France wanted to do something to protect children. They tried to do this with children’s literature laws. No violence could be described. No favorable depiction was allowed of “lying, stealing, laziness, cowardice, hatred… or any acts that are classified as crimes or misdemeanors.” These regulations inevitably led to a major censorship of the tale.18 Several pages were simply omitted. The French version has been charitably called an “adaptation,” but the words “mutilation” and “disfigurement” have also been used. The adaptation tried to make Pippi “a fine young lady instead of a strange maladjusted child.” This “dangerous” girl became an “anarchist in a straitjacket.”19,20 Her habit of ignoring adult authority was eliminated, as was any idea of children’s rights. Her improbable tall tales, which Swedish children understood to be fabrications, were cut out. Lindgren’s “spoken” narrative style was changed into “very conventional language.” When an uncensored translation appeared in France in 1995, readers were amazed after comparing it to the earlier, censored translation.21

The character of Pippi has not escaped the attention of psychiatrists. Much like Dr. Heinrich Hoffmann’s character, Der Struwwelpeter22 (“Fidgety Phil,” “Shock-headed Peter”), who has been retrospectively diagnosed as having Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Pippi has been given diagnoses of “ADHD traits and a hint of Oppositional Defiant Disorder.”23

The “superhuman” or “Übermensch” label coined by Friedreich Nietzsche has been applied to Pippi. The term has come to be incorrectly associated with the Nazi ideology of “Aryan superiority” and racism. Nietzsche had in mind a “free spirit,” someone not “bound by common beliefs and conventions.” It has nothing to do with physical strength (although Pippi certainly has that), nor is it a question of achievement. Rather, is describes “an approach to life.” Lindgren herself called Pippi “a little Übermensch in the shape of a child.”24

The Pippi Longstocking stories are better known in former Communist Eastern Bloc countries than in Western countries. The former USSR was, and the later Russian Federation is, very appreciative of Astrid Lindgren, who received the Tolstoy Medal in 1987. It is said in Russia, that Astrid Lindgren was able to understand children’s thinking. In 1996, the Russian Academy of Science named an asteroid after Lindgren, who said, “From now on, call me Asteroid Lindgren.”25

References

- Jorgen Gaare and Øystein Sjaastad. Pippi och Sokrates: Filosofiska Vandringen i Astrid Lindgrens Värld. Stockhom: Natur och Kultur, 2002.

- “Astrid Lindgren.” Wikipedia.

- “Astrid Lindgren bibliography.” Wikipedia.

- “Pippi Longstocking.” Wikipedia.

- Astrid Lindgren. ”Känner du Pippi Långstrump?” In Sagor: Hyss & Aventyr, Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren, 2010.

- Kelsey McLendon. “Parody and the pen: Pippi Longstocking, Harriet M. Welsch, and Flavia de Luce as disrupters of space, language, and the male gaze.” Master’s Theses and Doctoral Dissertations, 907, 2016. https://commons.emich.edu/theses/907/.

- McLendon, “Parody and the pen.”

- “Pippi Longstocking,” Wikipedia.

- Paul Binding. “Long live Pippi Longstocking: The girl with the red plaits is back.” Independent, August 26, 2007.

- Kate Erbland. “25 book characters you wanted to be as a kid,” Bustle, June 11, 2014.

- Susanna Forest. “Pippi Longstocking: The Swedish superhero,” The Telegraph, September 29, 2007. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/3668234/Pippi-Longstocking-the-Swedish-superhero.html.

- “Pippi Longstocking,” Wikipedia.

- “Pippi Långstrump.” Swedish Wikipedia. https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pippi_L%C3%A5ngstrump.

- “Pippi Longstocking,” Wikipedia.

- “Pippi Longstocking,” Wikipedia.

- “Pippi Longstocking,” Wikipedia.

- Gaare and Sjaastad, Pippi och Sokrates.

- Sophie Heywood. “Pippi Longstocking, juvenile delinquent? Hachette, self-censorship, and the moral reconstruction of post-war France.” Itinéraires, 2015-2, 2016.

- Christina Heldner. “Une anarchiste en camisole de force: Fifi Brindacier ou la metamorphose de Pippi Långstrump.” La Revue des Livres pour Enfants, 145, Spring 1992. https://cnlj.bnf.fr/sites/default/files/revues_document_joint/PUBLICATION_3354.pdf.

- Emilie Brouze. “Libre, féministe, elle-même: Fifi Brindacier, badass avant l’heure.” Nouvel Observateur. January 10, 2018.

- “Pippi Longstocking,” Wikipedia.

- Howard Fischer. “Dr. Heinreich Hoffman and Der Struwwelpeter.” Hektoen International, Fall 2021.

- Sarah Kittel-Schneider et al. “Non-mental diseases associated with ADHD across the lifespan: Fidgety Philipp and Pippi Longstocking at risk of multi-morbidity.” Neuroscience and Behavioral Reviews, 132, 2022.

- Michael Tholander. “Pippi Longstocking as Friedrich Nietzsche’s overhuman.” Confrero, 4 (1), 2016.

- Jean-Baptiste Coursaud. “Fifi anarchiste et…communiste? L’oeuvre d’Astrid Lindgren en RDA, Pologne, et URSS.” La Revue des Livres pour Enfants, 238, December, 2007.

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., has lived in Sweden for the past ten years, and in researching this article has finally found a use for his knowledge of Swedish.

Leave a Reply