JMS Pearce

Hull, England

Napoleon Bonaparte was born on the French island of Corsica on August 15, 1769. His colorful life, illnesses, and military exploits have been extensively recorded.1 On 17 October 1815, after the forty-five-year-old Napoleon’s famous defeat near Waterloo, the allies banished him to St. Helena, a subtropical island in the South Atlantic Ocean, 1,200 miles from Africa. Napoleon’s household at St. Helena consisted of several titled generals, Count Las Cases his biographer, and Dr. Barry E. O’Meara, a medical volunteer who remained Napoleon’s supporter and medical attendant until 1818 when he was banished after a politically charged and personal dispute with the British governor Sir Hudson Lowe.

From 1818, Napoleon suffered increasingly from nausea, stomach pains, urinary problems, and seemed in very poor health in a damp, dilapidated house. Not until September 1819 was O’Meara replaced by Dr. Antommarchi, a native Corsican and professor of anatomy at Florence who was sent by the Bonaparte family. Napoleon was suffering from recurrent dysuria, abdominal pain, hemorrhoids, vomiting, and hematemesis.2

His health deteriorated in April 1820, and by September the attacks of vomiting, stomach pain, headache, anorexia, and constipation became more frequent. On good days he was still able to take a stroll, but by December he could hardly make a few steps without extreme fatigue.3 He confessed his fears, knowing that his father had died of stomach cancer.

Dr. Archibald Arnott, Surgeon of the 20th Regiment, attended him frequently with Antommarchi; neither made the correct diagnosis. On 15 April 1821, Napoleon dictated his will and on 27 April, he began to have “coffee ground” gastric hemorrhages.

In several papers Napoleon’s doctors have been roundly criticized, particularly Antommarchi, the “much misunderstood Malvolio of the drama of St. Helena.”4 But he trusted Arnott, “a man of honor and a gentleman.” In April 1821 he gave his final instructions to Antommarchi: “After my death I wish you to make an autopsy. Do not let any English physician other than Dr. Arnott touch my body.” On May 5, after further hemorrhage, delirium, and coma, he died.

Pathology

Dr. Antommarchi, in the presence of Arnott5 and five other surgeons, performed the necropsy on May 6. The body was feminized, covered by a deep layer of fat; the skin was white, hairless, and delicate. The testicles and penis were atrophic. There were about three ounces of a yellowish fluid in the left pleural cavity and eight ounces in the right. The upper lobe of the left lung contained several tuberculous excavations. Arnott, an eyewitness at the necropsy, stated that the lungs were normal.

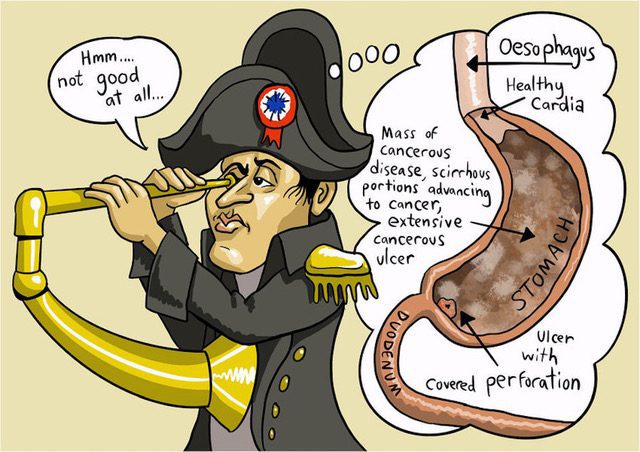

The peritoneum was covered with a viscous fluid. On the anterior surface of the stomach at the lesser curvature near the pylorus was a complete perforation large enough to admit the little finger. This opening was completely closed with adhesions. On opening the stomach, it was found to be full of a large quantity of “coffee ground” material of an acid-putrefying odor, and the internal surface of the stomach was almost completely covered by a carcinomatous mass; only a small part of the cardiac extremity seemed free of the disease. All the adjacent lymph nodes were greatly enlarged and cancerous.3 There was dispute whether the liver was enlarged but no definite pathology was disclosed.

Leonard Guthrie wrote convincingly that at autopsy his fine skin, obesity, disappearance of hair, feminine appearance, and genital atrophy suggested hypopituitarism developing in later life.6

Numerous illnesses have been ascribed to Napoleon, though the fatal outcome was undoubtedly caused by gastric carcinoma. One in particular was in 1961 when samples of his hair (taken over many years) contained large amounts of arsenic.7 The wallpaper in his room at Longwood House in St. Helena in 1819 was analyzed in 1982 and found to contain arsenical pigment in levels capable of causing illness but probably not death.8 More sophisticated serial analyses showed no sudden increase of the hair arsenic contents, as one would expect if a lethal dose had been administered during the emperor’s last six months of life.9

Yet another opinion expressed by forensic scientists in 2004 speculated that the final event was torsades de pointes caused by chronic exposure to arsenic and medications that included tartar emetic (antimony potassium tartrate), one huge dose of calomel (mercurous chloride), and quinine in Jesuit’s bark, another cause of QT prolongation.10

Despite the many confusing medical factors, the autopsy proved that a perforated scirrhous gastric carcinoma was the cause of death.2,3 The failure of his doctors to make the diagnosis is not surprising since benign and malignant gastric ulcers had not been described until Cruveilhier’s account in Traité d’anatomie 1835, and the clinical symptoms of gastric cancer reported by Bayle in the same decade. The question of hypopituitarism remains unresolved since the cranial contents and pituitary were not examined.

References

- Roberts A. Napoleon: A Life. Penguin Books, 2015.

- Robinson JO. The failing health of Napoleon. J Roy Soc Med 1979;72:621-3.

- Bechet PE. Napoleon—His Last Illness And Postmortem Bull N Y Acad Med. 1928 Apr; 4(4): 497-502.

- Keith A. An address on the history and nature of certain specimens alleged to have been obtained at the post-mortem examination of Napoleon the Great. Br Med J. 1913;1(2715):53-59.

- Arnott A. An Account of the Last Illness, Decease and Post Mortem Appearances of Napoleon Bonaparte. London: John Murray, 1822.

- Guthrie LG. Did Napoleon Bonoparte suffer from hypopituitarism (dystrophia adiposo-genitalis) at the close of his life? Lancet 1913;1:137.

- Forshufvud S, Smith H, Wassen A. Arsenic content of Napoleon I’s hair probably taken immediately after his death. Nature. 1961;192:103-105.

- Keynes M. The death of Napoleon. J R Soc Med. 2004 Oct;97(10):507-8.

- Lugli A, Carneiro F, Dawson H, et al. The gastric disease of Napoleon Bonaparte: brief report for the bicentenary of Napoleon’s death on St. Helena in 1821. Virchows Arch. 2021 Nov;479(5):1055-1060.

- Mari F, Bertol E, Fineschi V, Karch SB. Channelling the Emperor: what really killed Napoleon? J R Soc Med. 2004;97(8):397-399.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.

Leave a Reply