JMS Pearce

Hull, England

“My words fly up, my thoughts remain below: Words without thoughts never to heaven go.”

When Claudius in Shakespeare’s Hamlet (III.3) speaks this line, he reminds us of the singular importance of the use of words, and hence the need, even for medical writers, to refer continually to fine dictionaries. Noah Webster set out to record and validate the variations in American English from conventional and specialized English dictionaries.

Medical dictionaries

Before the eighteenth century, there were several compendia and glossaries of botanical remedies, medical folklore, and poisons, but few would we now regard as medical dictionaries.1 Garfield’s A Physical Dictionary (1657) that started as a glossary, Stephen Blankaart’s Lexicon Medicum Graeco-Latinum (1642, English translation 1684), and the Danish Thomas Bartholi’s Anatomia Reformata, (1651) have variously been cited as the first medical dictionaries.2 James’s A Medicinal Dictionary (1743–1745) and Motherby’s A New Medical Dictionary (1775) were major and lengthy specialized reference works. Many others were subsequently published. The nineteenth and twentieth centuries’ Robley Dunglison’s A New Dictionary of Medical Science and Literature, first published in 1833 (which became Stedman’s), Taber’s, Gould’s, Black’s, Dorland’s, and other worthy tomes gradually found common usage amongst medical students and practitioners.

Conventional dictionaries of English arose separately.

Conventional dictionaries

Dr. Samuel Johnson defined:

Dictionary: A book containing the words of any language in alphabetical order, with explanations of their meaning, a lexicon, a vocabulary, a word-book.

The first of these was probably Robert Cawdrey’s A Table Alphabetical (1604), listing only 3,000 words. Before Johnson, writers were impeded by a limited source of words and by imprecise definitions. This blunted clear thought and ideation, which caused imperfect communications and hampered every type of knowledge—artistic, scientific, and medical. That was where the scholarly lexicographer Dr. Samuel Johnson stepped in.

Johnson’s A Dictionary of the English Language

Johnson defined a lexicographer as “a writer of dictionaries; a harmless drudge, that busies himself in tracing the original, and detailing the signification of words.” His dictionary was published on April 15, 1755. It was the most authoritative and influential dictionary in the English language. Its two volumes contained a list of c. 42,000 words and 114,000 quotations. Many are still appropriate.

The Oxford English Dictionary

More than a century later, the Oxford English Dictionary began in 1878 when the Philological Society of London secured as editor the “unconventionally attired” James Augustus Henry Murray (1837–1915), a Scottish teacher at Hawick Grammar School.3 After five years, the first fascicle, A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles; Founded Mainly on the Materials Collected by The Philological Society was issued in 1884, covering only A-ant. The twenty-volume second edition 1989, weighs 62.6 kg and contains c. 500,000 words and phrases past and present from across the English-speaking world. Several well-known shortened versions are popular.

Murray importantly urged the principle that dictionaries should describe, not prescribe. They record the actual use of words but do not criticize the fluctuating fashions of language,4 which vary in different times and cultures. The Oxford English Dictionary exhaustively lists every word in current usage but does not delete obsolete or archaic words and phrases. A veritable glut of excellent but less comprehensive dictionaries followed.

A Compendious Dictionary of the American Language

There have been many failed attempts to reform English, such as those that tried to make spelling conform to phonetic pronunciation. In America and the commonwealth countries at the turn of the nineteenth century, English language orthography, syntax, and pronunciation had developed their own styles. It was two-way traffic: many new words, spellings, and syntax were imported into common English usage.

Not overendowed with modesty, at the age of twenty-four, Noah Webster styled himself “the prophet of language to the American people.” Webster’s dictionary of Americanisms (a word first used in 1779) recognized the changes and variations within the language. An obsessive patriot, he rightly recorded them because Americans were no more obliged to follow English spelling than they were obliged to follow English laws, traditions, or diet. On June 4, 1800, Webster announced his intention in a Connecticut newspaper to compile a “Dictionary of the American Language.”

In his preface he noted:

It is not only important, but, in a degree necessary, that the people of this country, should have an American Dictionary of the English Language; for, although the body of the language is the same as in England, and it is desirable to perpetuate that sameness, yet some differences must exist. Language is the expression of ideas; and if the people of one country cannot preserve an identity of ideas, they cannot retain an identity of language.5

He first published A Grammatical Institute of the English Language (1783–1785) known for its colored binding as the Blue-Backed Speller, which included The American Spelling Book (1787). In 1829, a new edition, The Elementary Spelling Book, sold ten million copies. It standardized acquired American orthography and spelling.

It is paradoxical that his first American Spelling Book (1783) rejected spellings that today characterize American English. He refused at first to drop the “u” from colour, favour and honour because “they have omitted the letter that is sounded, and retained one that is silent; for the words are pronounced onur, favur.” But Webster resiled and included many extant variant spellings in his dictionary. However, before the Pilgrim Fathers had time to change their native language, Shakespeare had used the spelling honor may times in his First Folio (1623) and often spelt humor rather than humour, center rather than centre. American spellings criticized by the British include: –ize for –ise as in realize for realise, criticize for criticise; yet they are soundly based since –ize is closer to the original Greek. Thus, pretentious but misinformed British protestations that such spellings are spoliation(s) coined in America are false. Amongst many alterations, Webster preferred words ending in –er where the British use –re as in meter, theater, center; and the single l in place of the double ll in jeweler, woolen, marvelous. However, he preferred ll where the British use a single l in enroll, fulfill, installment. He sought simplicity and it is hard to deny that center makes more sense phonetically than centre.

Noah Webster (1758–1843), born in West Hartford, Connecticut, was a deeply religious man, an ardent patriot, lawyer, lexicographer, and teacher.6 He attended Yale University and taught in New York. Grammar and spelling were his initial concerns. He was rudely critical of Johnson’s dictionary.

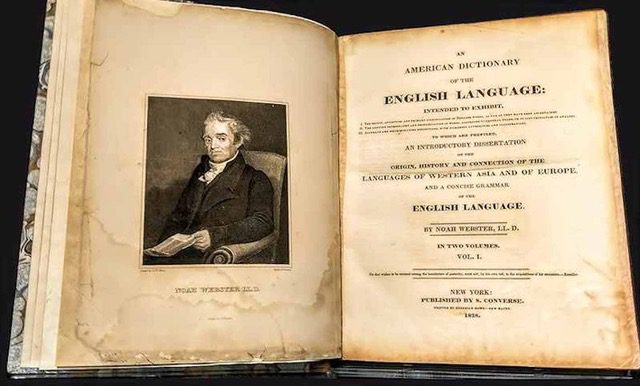

His first general dictionary, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, appeared in 1806. It contained simplified definitions and over 40,000 entries, many of American or Native American derivation. Because of meager sales of only 2,500 copies, he was forced to mortgage his home. He followed this with his 70,000-word American Dictionary of the English Language (1828) (Fig 1), which although it had its critics, was instantly successful and contained Native American words, for example: “skunk,” “squash,” and “lacrosse.” Many word definitions refer to the King James Bible. His principle was that spelling, grammar, and usage should be based on the living spoken and written language of America. Thus, almost single-handedly, he established the independent vitality of American English.7

George and Charles Merriam later developed the Merriam-Webster dictionary series. A new unabridged edition was published in 1841 with a second edition in 1845. Since 1964 it has been a subsidiary of the Encyclopædia Britannica. Webster’s Third New International Dictionary of the English Language (1961) contains more than 470,000 entries and provided the most extensive record of American English and slang. Webster-dictionary.org is a free online English dictionary and thesaurus with more than 240,000 words and definitions. Several specialized editions emerged, including the Merriam-Webster’s Medical Dictionary.

In addition to his arduous writing of the great dictionary, Noah Webster fought for copyright laws, a strong federal government, and universal education, and he fiercely opposed slavery. He wrote several other books and corresponded with George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. He aided the foundation of the private liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts. The New York Times (May 27, 2011), though it acknowledged Webster’s accomplishments, described him as “dislikable, arrogant, humorless and socially tone-deaf.”

Many competing independent American dictionaries have subsequently surfaced, notably the New Oxford American Dictionary, the Random House American College Dictionary, and The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language with illustrations in 1969. None have been more thorough, none more critical, and none have surpassed the industry and quality of the wordsmith Webster.

We get a glimpse of his personality when in 1833 he revised and modernized the King James version of the Bible with euphemisms to replace words that he deemed indelicate or inapt. He wanted his dictionaries to set a moral standard: unlike Johnson’s, his early editions did not include words such as “fornication” and “whore.”8

He married Rebecca Greenleaf in 1789; they had two sons and six daughters. The Noah Webster House and museum are sited in West Hartford, Connecticut. He is pictured on a four-cent US stamp of 1958.

Webster’s dictionaries had a different emphasis but complimented those of Britain’s James Murray. He died shortly after a stroke with pleurisy in May 1843, and was buried in the New Haven Grove Street cemetery.

References

- Osler W. Incunabula medica; a study of the earliest printed medical books, 1467-1480. Oxford University Press 1923.

- Roderick McConchie, Jukka Tyrkkö (eds). A Physical Dictionary (1657): The First English Medical Dictionary. In: Historical Dictionaries in their Paratextual Context. De Gruyter 2018.

- Winchester S. The Meaning of Everything: The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2003.

- Pearce JMS. Dr. William Minor and the Oxford English Dictionary. Hektoen Int. Spring 2021.

- Webster Noah. An American Dictionary of the English Language 1828.

- Unger HG. Noah Webster: The Life and Times of an American Patriot. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 1998.

- Yazawa Melvin. Webster, Noah (1758–1843), lexicographer. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Sep 23, 2004. Accessed Nov 6, 2023.

- Martin Peter. The Dictionary Wars: The American Fight Over the English Language. Princeton Univ Press. 2019.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.

Leave a Reply