JMS Pearce

Hull, England

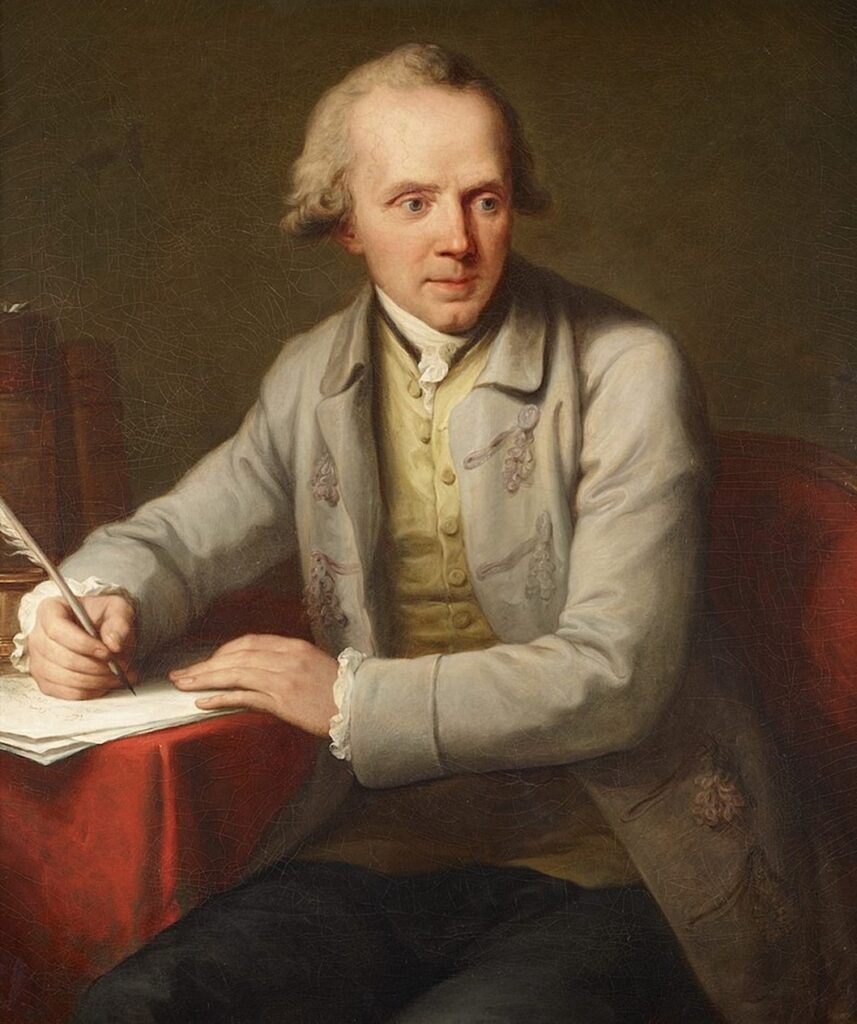

The Swiss physician Samuel Auguste Andre David Tissot (1728–1797)*1,2 (Fig 1) spent his professional life in Lausanne, despite tempting offers made by the royalties of Poland and England. He developed into one of the most influential physicians of the Age of Enlightenment: an advocate of rational medicine as opposed to the prevailing widespread charlatanism.1 Born in Grancy, he studied at the Academy of Geneva and at the Medical Faculty of Montpellier. Tissot was elected Professor of Medicine at Lausanne and to several learned scientific bodies, including the Royal Society in 1759.

He was best known for his book Avis au Peuple sur la Santé (1760), a tract on medicine for the layman so popular that it spawned ten editions and was translated into English.3,4 It aimed to give the public an explanation and understanding of the principles of hygiene, diet, and prevention of disease; it gave advice on self-treatment for those who lived in remote rural areas. He was also concerned with the upper classes, as shown in An Essay on the Disorders of People of Fashion; and a Treatise on the diseases incident to literary and sedentary persons (1772).

Before Jenner’s smallpox vaccination in 1796–8, Tissot promoted the use of variolation in Practical observations on the small pox, apoplexy, and dropsy, a series of letters to Albert von Haller (1772). (Lady Mary Wortley Montagu had introduced variolation to Britain in 1721.)

Epilepsy

Of his scientific works, his most important was his two–volume Traité des nerfs et de leurs maladies (I778) (Fig 2), in which with singular compassion he described the symptoms and the natural history of many types of epileptic fits that founded much subsequent research. Tissot refuted the reputed influence of the moon and pregnancy, believing that the brain was solely responsible. He also believed that sexual excess or masturbation could cause epilepsy (vide infra).

He identified essential, idiopathic epilepsy and described the seizure types grands accés and petits accés (more widely called grand mal and petit mal). He discussed melancholia, nervous debility, and hysteria, and considered psychopathology and a simple concept of the unconscious and the subconscious mind. The Traité included sections dealing with the anatomy and physiology of the nervous system, apoplexy, paralysis, epilepsy, catalepsy, migraine, and insanity. He supported his famous contemporary Albert von Haller’s fundamental concept of neural “irritability,” which showed by experiment that all structures containing nervous tissue and muscle fibers were both sensible and irritable.

Migraine

Galen had distinguished hemicrania from other headaches but thought they were caused by the “ascent of vapours, either excessive in amount or too hot, or too cold.” For many centuries thereafter, scientific hypotheses of migraine’s etiology were stultified. Before Tissot, Willis in De cephalalgia had recognized the cerebral nature of migraineurs’ vomiting. Tissot advanced description and understanding in an 83-page section on migraine in his Traité des nerfs.5 He followed Wepfer in providing a thorough clinical description.6 He recognized that it affected the nervous system and reported hemianopia, hemiplegia and typical visual prodromata:

Migraine is distinguished by the severity of the pain, by a kind of periodical return, by the similarity of different attacks, by its recurrence independently of those accidental causes which determine other kinds of headache. We may say of every seizure that its onset is spontaneous and somewhat sudden, sometimes with a slight sense of chilliness, and then the paroxysm is often more violent; the pain, however, does not set in at first in its full severity, which it does not usually attain for an hour and a half, and then remains at the same intensity for some hours…

After the headache vomiting frequently sets in, which is attended by relief; the pain diminishes, and the patient sometimes falls into a tranquil sleep for some hours, and awakes feeling quite well.7

He also noted that gastric symptoms might precede or initiate attacks:

…A focus of irritation is formed little by little in the stomach, and that when it has reached a certain point the irritation is sufficient to give rise to acute pains in all the ramifications of the supraorbital nerve.

He described clearly the periodicity and the pattern of migrainous attacks.8 He also reported the full gamut of visual, sensory, and dysphasic phenomena during the aura, and noticed trigger factors, which could excite or precipitate migraine. A century later, the noted migraine authority Edward Liveing acknowledged: “This disposition, which Tissot terms proëgumenal, deserves the greatest attention in connexion with preventive treatment …”9

Noted physicians of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, who included Heberden, Whytt, Cheyne, Sydenham, and Willis, made little distinction between physical and mental symptoms. They recognized both as manifestations of disorders of the nervous system.8

Onanism

This topic concerning masturbation was not Tissot’s most creditable work.

The name onanism originates in Genesis 38:7–10:

And Er, Judah’s firstborn, was wicked in the sight of the Lord; and the Lord slew him. And Judah said unto Onan, Go in unto thy brother’s wife, and marry her, and raise up seed to thy brother. And Onan knew that the seed should not be his; and it came to pass, when he went in unto his brother’s wife, that he spilled it on the ground, lest that he should give seed to his brother. And the thing which he did was evil in the eyes of the Lord: wherefore he slew him also.

Tissot published a rambling, nugatory text: A treatise on the diseases produced by onanaism on the ill effects of masturbation on both mind and body. It was first published in Latin in the 1758 edition of his Dissertatio de febribus biliosis and translated into English in 1832. The book recounts histories from his patients and from patients of other renowned European doctors to support his claim that masturbation (“self pollution”) is deleterious to a person’s body and mind. Perhaps influenced by his profound Calvinistic dogma, Tissot ascribed to onanism a huge range of symptoms affecting almost every bodily organ:

…There is another humor, the seminal liquid, which has so great an influence over the forces of the body, and over the accomplishment of the digestions which repair them, that the Physicians of all ages have unanimously believed, that the loss of one ounce of this humor weakened more than the loss of forty ounces of blood.

…An immoderate profusion of seed is pernicious, not only through the waste of that most useful humor, but also through the over-frequent repetition of that convulsive motion which is produced by the emission.

…debility, immobility, convulsions, emaciation, dryness, pains in the membranes of the brain, impairs the senses, particularly that of sight, gives rise to dorsal consumption, indolence, and to the several diseases connected with them.

To further his claim, he quoted from ancient physicians Galen and Celsus, as well as from Herman Boerhaave and numerous other contemporary physicians. However, these citations often refer indiscriminately to “venery,” excesses and perversions of sexual activities in general.

In tune with prevailing religiosity, this did not harm Tissot’s reputation, for in 1787 Napoleon Bonaparte, then an artillery officer, wrote in April 1787:

Sir,

You have spent your days in treating humanity and your reputation has reached even into the mountains of Corsica where medicine is not much used…Not having the honour of being known to you and with no right other than the respect I have for your works,…I ask advice for one of my uncles who has the gout

Interestingly, Tissot did not reply and wrote on the back of the letter: “Unanswered, of little interest.”

Note

* There may be confusion about his name. Morton’s medical bibliography refers to Simon André Tissot, but gives the exact dates of birth and death. Garrison’s History of Neurology refers to him as SAAD Tissot.

References

- Jenkins JS. Dr Samuel Auguste Tissot. J Med Biogr. 1999;7(4):187-91.

- Karbowski K. Samuel-Auguste Tissot (1728-1797): On the 200th anniversary of his death. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1997;127(27-28):1163-7.

- Emch-Dériaz A. Tissot: Physician of the Enlightenment. New York: Peter Lang, 1992.

- Bucher HW. Tissot und sein Traité des Nerfs. Zurich: Juris-Verlag, 1958.

- Tissot SA. Traité des nerfs et de leurs Maladies. (Bayles edition) pp. 383-8. Cited in Liveing E. On Megrim, Sick headache, and some Allied Disorders: A Contribution to the Pathology of Nerve storms. London: Churchill. 1873.

- Karbowski K. Samuel Auguste Tissot (1728-1797). His research on migraine. J Neurol. 1986;233(2):123-5.

- Tissot SAAD. De la migraine, Oeuvres de Monsieur Tissot, nouvelle edition augmentee et imprimee sous ses yeux.1790;13;383-8.

- Pearce JMS. Samuel Auguste Tissot (1728-1797) and Migraine. Cephalalgia. 2000;(7):668-70.

- Pearce JMS. Edward Liveing’s Theory Of Nerve Storms In Migraine. In: A short History of Neurology. ed. F. Clifford Rose. Oxford. Butterworth 1999. pp. 192-203.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of science and medicine.

Leave a Reply