JMS Pearce

Hull, England

One of the greatest mysteries about human beings is the contrast between their intelligence, inventiveness, creativity and their extraordinary compulsion for self-destruction and violence. How can humans, blessed with compassion, charity and sympathy, combined with knowledge, self–awareness and understanding, so readily embrace acts of violence, destruction of ourselves both individually and collectively? Why, without heeding our history, do we tolerate and accept the depraved murder of thousands of our innocent brethren in warfare, a trend pervading all races throughout history?* And why do we annihilate the planet that supports our very existence?

The origins and causes of such ubiquitous conflicting facets of human behavior are matters of surmise. Scientists, philosophers and artists of all cultures, throughout the tides of human time have abjectly failed to produce any ripple of rational explanation. Psychologists have as always produced labels, but labeling describes rather than explains the issues. They talk of xenophobia, the dislike or hatred of strangers or foreigners, and its converse xenophilia, the affection or love of them. These traits are found in the higher primates, which may provide one curious fragment of understanding, since many aspects of both the human genome and behavior closely resemble that of higher primate species, the apes.

The chimpanzee genome was sequenced in 2005, the bonobo genome in 2012. Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) are our closest relatives, sharing 99 percent of our DNA, gorillas 98 percent, and orangutans 97 percent, bonobos 98.7 percent. Bonobos (Pan paniscus) have been called “pygmy chimps” or “hippie chimps,” the primates that make love, not war. Bonobos are just over one meter tall, weighing 30 to 40 kg. They resemble small chimpanzees with whom they share 99.6 percent of their DNA.

Wild bonobos are found in forests south of the Congo River in the Democratic Republic of Congo. An endangered species, population currently estimated at 10,000 to 20,000, they have been victims of man’s hunting and of habitat loss from destruction of forests for logging.

Bonobos and chimpanzees behave very differently, despite their genetic similarity.1 Human behavior resembles in part both species. Bonobos have a unique social structure characterized by cooperation, female dominance, and the use of uninhibited sexual behavior to resolve conflicts. In contrast to the chimpanzees’ xenophobic aggression and intergroup murder, research at Lola ya Bonobo sanctuary has shown bonobos to be gentle, compassionate, and xenophilic.1,2

In man, an association of clinical empathy with improved therapeutic outcomes has been asserted in many clinical settings. These social traits may reflect certain aspects of the evolution of human social behavior. They have been attributed to delayed development (“juvenilization in a set of traits that are genetically linked”) of social behavior and cognition in bonobos as compared to chimpanzees.3 Chimpanzees, though sophisticated in social behavior and what we take to be intelligence, resemble humans in their destructive behavior. Acting in groups, they fight and kill other chimpanzees which threaten their breeding, territory, or food supply.

In bonobos, although limited fighting does occur, territorial patrols, infanticide, and lethal intergroup aggression have never been observed.4 Neighboring groups maintain social and spatial borders without hostility. They often use hugging and copulation to settle disagreements and calm anxieties. Different bonobo groups peacefully share feeding areas and hunting grounds.5 When bonobos offered food were given a choice to eat alone, or to give it either to a bonobo of the same group or to a stranger bonobo, they usually shared with the stranger first, then with the friend (xenophilia).6 They also display caring for their injured, in an empathetic manner.

Like humans, both bonobos and chimpanzees use tools. They also show contagious yawning, a form of “motor or mirror mimicry,” which, though common in other vertebrates, is arguably a sign of empathy. Chimpanzees have more than seventy specific gestures, which are probably precursors of vocalized language.7 Many of these are shared with bonobos; human children understand many ape gestures. Bonobos have complex vocalizations and gestural communications that hint at the evolution of human language, perhaps present in primitive form in a postulated common ancestor of the higher apes.

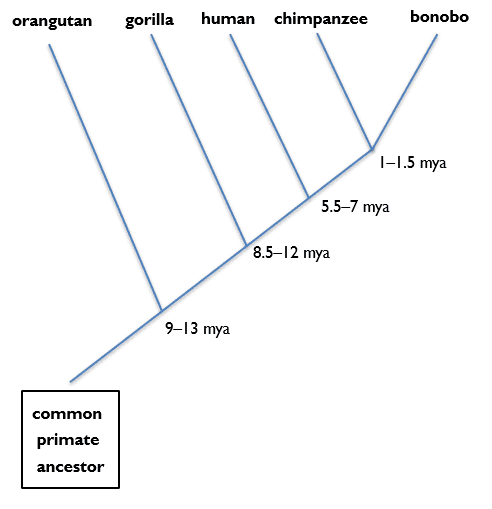

When did these species evolve? Modern humans separated from the lineages leading to chimpanzees and bonobos 5.5–7 million years ago (mya), from the gorillas 8.5–12 mya, and from orangutans 9–13 mya. The banks of the Congo River separated chimpanzees and bonobos about 1–1.5 mya.

Although we can trace the evolution of anatomical and many physiological aspects of the animal kingdom, our understanding of mental, emotional, and behavioral evolution is clouded and largely conjectural. Xenophilia in bonobos recalls empathy and sympathy in humans.8 Humans also can act like chimpanzees in the violence and killing of their own and other species. Higher primates live in communities and learn which behaviors are rewarded and which are punished or disadvantageous. One opinion is that primate aggression is a primal strategic response to environmental conditions, though this is not always obvious in the acquisitive aggression of homo sapiens.

It is argued that empathy and xenophilia bind social animals in behavior that favors survival by natural selection. Hare infers Survival of the Friendliest; Homo sapiens evolved via selection for “prosociality.”4 This trait is evident in modern-day sympathetic, selfless donations of organs for transplantation and less dramatically in numerous charitable gifts, foreign aid, and donations in natural disasters and warfare. But how harshly does this contrast with the materialism and violence of much of modern life?

Xenophilia4 may have evolved through natural selection in social species; the benefits of bonding between outsiders may outweigh the risk of fighting and killing, a lesson not yet learnt by man. A small but significant contribution of genetic inheritance has been demonstrated in studies of human empathy. De Waal concluded that innate feelings of morality and empathy relate both to environmental factors needed for survival and to factors resulting from biological (i.e. genetic) evolution.1 However, a question rarely confronted is that although survival of the fittest is a mechanism, what drives the quest, and what are the consequences of survival? If survival was more easily attained then population numbers and longevity would increase. This would impose increased competitive stresses on the availability of territory and food supplies that might result in a vicious circle of more belligerent behavior. In addition it would cause greater environmental waste and pollution.

We don’t know whether the human and bonobo’s xenophilia is an instance of convergent or of divergent evolution. It is however, not unique to homo sapiens as mistakenly supposed in the past.

Like the celebrated paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, we may speculate that the more peaceful bonobo has retained traits, also evident in ourselves, from a common ancestor dating from thirteen million years ago. But, quo tendimus: where are we going next? The evolutionary anthropologist Brian Hare wishes more people could discover what bonobos can teach us about human nature—”We have a lot to learn from them.”

End note

* By chance this was written before the current Israel/Hamas debacle.

References

- De Waal F. Bonobo: The Bonobo and the Atheist: in Search of Humanism Among the Primates. W. W. Norton & Company; Reprint edition (2014).

- Surbeck M, Boesch C, Girard-Buttoz C, Crockford C, Hohmann G, Wittig RM. Comparison of male conflict behavior in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and bonobos (Pan paniscus), with specific regard to coalition and post-conflict behavior. Am J Primatol. 2017 Jun;79(6).

- Wobber V, Wrangham R, Hare B. Bonobos exhibit delayed development of social behavior and cognition relative to chimpanzees. Curr Biol. 2010 Feb 9;20(3):226-30.

- Tan J, Ariely D, Hare B. Bonobos respond prosocially toward members of other groups. Sci Rep 7, 14733 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-15320-w.

- Samuni L, Wegdell F, Surbeck M. (2020) Behavioural diversity of bonobo prey preference as a potential cultural trait. Elife. 2020 Sep 1;9:e59191.

- Hare B, Woods V. Survival of the Friendliest: Understanding Our Origins and Rediscovering Our Common Humanity. Random House, 2020.

- Hobaiter C, Graham KE, Byrne RW. Are ape gestures like words? Outstanding issues in detecting similarities and differences between human language and ape gesture Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 2022; B3772021030120210301. http://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2021.0301. [1] Pearce JMS. Empathy or sympathy? Hektoen International Winter 2023.

- Pearce JMS. Empathy or sympathy? Hektoen International Winter 2023.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.

Leave a Reply