Matthew Turner

Hershey, Pennsylvania, United States

In 1828 Scotland, two men committed a series of crimes that would earn them, as a contemporary newspaper described, “a conspicuous place in the annals of murder.”1 To both contemporaries and modern audiences, the gruesome story of Burke and Hare is “an endless source of morbid fascination.”1

For centuries, Western physicians were extremely limited in access to cadavers for dissection, for a number of cultural and religious reasons.2 Even as medical knowledge advanced, great stigma remained around dissection, often forcing medical schools and physicians into conflict with societal mores.2

In the early years of the nineteenth century, this was particularly pronounced in Scotland, where there was significant pressure for anatomy lecturers to supply cadavers for their students. Many students were encouraged to exhume newly buried corpses from local graveyards to ensure a steady supply of fresh cadavers to dissect. This became such an issue that the Edinburgh College of Surgeons attempted to forbid this in 1721, with little success. In 1744, 1748, and 1749, angry mobs attacked Glasgow University because of rumored dissections of stolen cadavers.3 As demand for “anatomical teaching” increased, there was greater emphasis on medical students performing dissections. By 1828, contemporary thought held that a medical student “should dissect at least three cadavers… two for studying the structure of the body and a third for practising [sic] operations.”3 Gradually, the previous system—where medical students dug up their own cadavers—shifted to “professional help,”3 where professional grave robbers, also known as “resurrection men”3 or “resurrectionists,” provided cadavers to medical schools.4 It was considered a profitable line of work: in some cases, surgeons would even pay exorbitant prices for the recovery of their now-deceased patients, to follow up on the operations that they had performed while they were living. Some resurrection men were infamous—one in Edinburgh named Andrew Merrilees, working in the early nineteenth century, was rumored to have “sold his own exhumed sister.”4 Most of the cadavers in Great Britain were exhumed from graveyards, usually potter’s fields in large cities and poor cemeteries. Gangs of resurrection men would typically claim a monopoly on certain cemeteries.4 The best could obtain a minimum of one corpse every month.5 A thriving industry soon arose to deter the resurrection men; large iron cages known as “mort safes” could be purchased to protect coffins and “keep a body snug until putrefaction would devalue it for the doctors.”6

William Burke and William Hare utilized a different approach from most resurrection men, one that focused on corpses that were even fresher than those that had been recently buried. The two men “drifted into murder for profit in an almost accidental manner.”4 Both from Ireland, the two men met in November 1827 when Burke and his mistress, Helen MacDougal, moved into a lodging house run by Hare and his wife.7 Their personalities were described as quite different; Hare was a cruel, vindictive man—his wife once described him as “devoted to the devil.” He was known to have a “ferocious and malignant disposition” and was once noted to have killed one of his employer’s horses, forcing him to flee from Ireland to Scotland. Hare’s “misanthropy of behavior”7 was a stark contrast to his co-conspirator. Burke, a former soldier,7 was remembered as “kind and serviceable, inoffensive and playful.”1 Despite these differences, the two men quickly became friends.7

According to their account, soon after the two men met, one of Hare’s other lodgers, a man named Donald, died of natural causes. At the time, he owed Hare £4 in rent. Although the parish was already in the process of preparing the body for burial—a carpenter even delivered a coffin to the lodging house—Hare “proposed that [Donald’s] body should be sold to the doctors.”5 Burke agreed to the plan. Together, the two men filled the coffin with tanner’s bark to simulate a body, then smuggled the corpse to Edinburgh University, asking for a famous anatomist, Dr. Alexander Monro. A student referred them to Robert Knox instead.5

Robert Knox was a widely respected anatomist in Edinburgh, and the head of a private anatomy school.6 As his extremely popular classes boomed in attendance—in 1828 he had a staggering 504 students—Knox promised his students that he would provide “an ample supply” of cadavers.6 This situation was further exacerbated by tensions between himself and Edinburgh University, as professors and private lecturers vied for an extremely limited cadaver supply.5 In 1828 alone, Knox required 400 cadavers to keep his classes supplied.1 Upon meeting Burke and Hare, he asked no questions and paid them £7 10s. His assistant encouraged the two men that Knox “would be glad to see them again when they had any other body to dispose of.”5 For all parties concerned, it was a splendid arrangement—Knox received a corpse in “superb condition” and the two men earned a sizeable payment.5

It was not long before Burke and Hare supplied Knox with another body. In either January or February 1828, another of Hare’s lodgers, a miller named Joseph, fell ill. This time, the two men murdered him. After inebriating him with whiskey, Hare suffocated Joseph as Burke laid across his chest to further restrict his breathing and movement. This method made the means of death nearly undetectable,5 and would eventually come to be known as “burking.”4

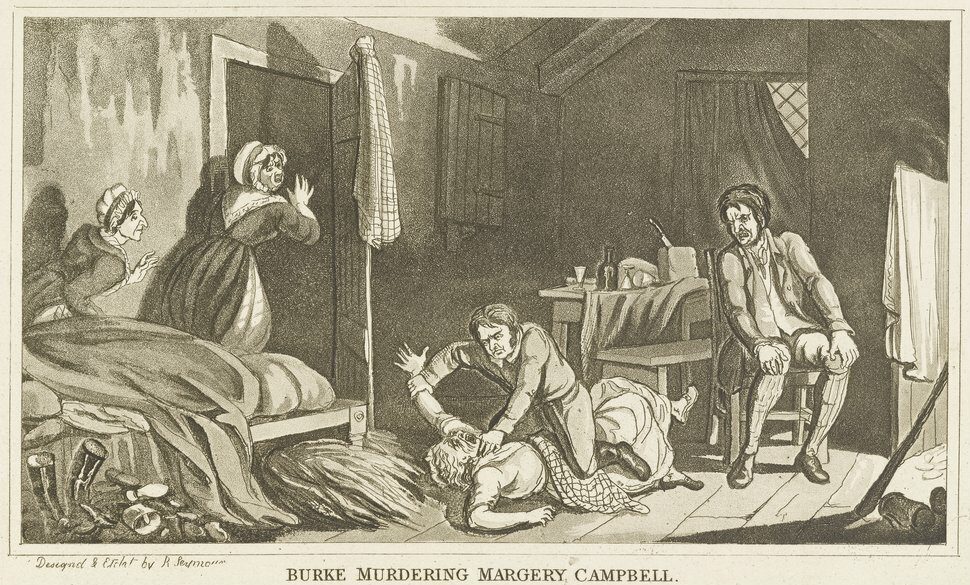

Over the next several months, Burke and Hare used this technique to murder another fifteen people, including more of Hare’s lodgers, prostitutes, and a mentally disabled eighteen-year old.4 Their last victim, Margaret Docherty, was killed on October 31.5 However, the two men had difficulty hiding her body, and were discovered at last.5

The story was immediately an “endless source of morbid fascination” to the public.1 During the trial, Hare turned on Burke, providing testimony that led to the other man’s public hanging on January 28, 1829.1 “Burking” entered the popular lexicon as both a means of murder as discussed above,4 and as a description of the many copycat crimes that exploded after the duo’s arrest. In 1832, Parliament passed the Anatomy Act in large part as a response to “burking” copycats.1

Although he was acquitted of any charges, Knox’s once sterling reputation suffered.8 Hare’s fate remains unknown. For his testimony, he was released from prison and vanished from history. Theories abound that he may have returned to Ireland, or that he “ended his days as a blind beggar in the East End of London.”1

Burke may have had the cruelest fate of all. Upon ordering the former soldier hanged, Justice Boyle told him: “Your body should be publicly dissected and anatomized.”9

It was.9

References

- Evans A. “William Hare the murderer.” International Journal of Epidemiology, 2010 Oct 1;39(5):1190-2.

- Swan RJ. “Prelude and Aftermath of the Doctors’ Riot of 1788: A Religious Interpretation of White and Black Reaction to Grave Robbing.” New York History, 2000 Oct 1;81(4):417-56

- Lennox S. Bodysnatchers: Digging Up the Untold Stories of Britain’s Resurrection Men. Pen and Sword; 2016 Sep 30.

- Arey LB. “Resurrection men-the rise of legalized dissection.” Quarterly Bulletin of the Northwestern University Medical School, 1940;14(4):209.

- Rosner L. The anatomy murders: being the true and spectacular history of Edinburgh’s notorious Burke and Hare and of the man of science who abetted them in the commission of their most heinous crimes. University of Pennsylvania Press; 2010.

- McCracken-Flesher C. The doctor dissected: a cultural autopsy of the Burke and Hare murders. Oxford University Press; 2011 Dec 19.

- Dudley-Edwards O. “Burke and Hare.” Birlinn; 2014 Oct 1.

- Bailey B. Burke and Hare: the year of the ghouls. Random House; 2011 Oct 14.

- Roughead W. Burke and Hare (Notable British Trials). Glasgow, Hodge. 1919.

DR. MATTHEW TURNER is a current first-year Emergency Medicine resident at Hershey Medical Center. He has long been fascinated by the intersection of medicine and history.

Leave a Reply