Matthew Turner

Hershey, Pennsylvania, United States

In the wake of the American Revolution, slavery remained a key part of the United States’ economy. Even the northern states were not exempt; in the waning years of the eighteenth century, slaves made up nearly 20% of the population of New York City alone.1 As a 2011 Lancet article notes, these slaves “were denied rights in life, and also in death.”1 Their dead were buried outside the city limits, “sometimes three or four to a grave” in a cemetery called the “Negroes Burying Ground” across from a pauper’s field for poor whites.1 The rest of New York’s population could expect to be buried among the sixteen churches with well-established cemeteries found throughout the city.2

Unfortunately, both of these cemeteries were located near Columbia College, the city’s only medical school.1 For centuries, Western physicians had “no legal access to human bodies” for the purposes of dissection.2 Although this was gradually beginning to change—in 1752, the English Parliament allowed London’s Surgeons’ Company access to cadavers of executed criminals,2 and the New York colonial government allowed a public dissection of another executed criminal3 several years later—great stigma remained around dissection for both whites and blacks, largely because of cultural and religious concerns.2 It was seen as such a cruel fate that, in an attempt to stop the practice of dueling, the 1774 Massachusetts legislature ruled that those killed while dueling “were to be delivered up for dissection to certain appointed physicians.”3 Given this stigma, early colonial physicians had to rely on “textbooks, from studies abroad, from prepared mounts imported from Europe, from occasional necropsies, and from amputated limbs” to develop their knowledge of anatomy.3 In the growing colonies, the very limited supply of cadavers was utterly insufficient. At Harvard Medical School, a single cadaver had to “do duty for a whole course of lectures.”3 Columbia College was no exception. Dr. Charles McKnight, a professor of anatomy and surgery at the facility, often “bemoaned the lack of cadavers for dissection.”1

In such an environment, grave-robbing—often known as “resurrection”—flourished.1 With the development of formaldehyde still decades in the future, bodies would last only a short time before decaying. With two cemeteries readily available, students of Columbia College began “resurrecting” cadavers from the Negroes Burying Ground and the pauper’s field.1 Tensions soon began to rise in the city, particularly from the black population and the poorer whites, who together made up the “principal victims chosen by the grave robbers.”3 On February 3, 1788, the black community formally petitioned the city’s Common Council regarding the grave robbing of the Burying Ground, noting that they would “not be adverse to dissection in particular circumstances, that is, if it is conducted with the decency and propriety which the solemnity of such occasion requires.”1 The petition was ignored. Just a few days later, the Daily Advertiser published a gruesome article claiming that “few blacks are buried, whose bodies are permitted to remain in the grave… human flesh has been taken up along the docks… this horrid practice is pursued to make a merchandise of human bones.”3 Barely a week later, a scandal broke out in the city when a body was stolen from a grave in Trinity Church, a brazen theft from the “respectable grounds of the first church of the city” rather than a cemetery filled with the marginalized of society.3 A nameless medical student attempted to defuse the situation through an anonymous letter, but “the article was so ludicrously tactless and insulting that the result was more damaging than helpful.”3

Tensions finally came to a boil on April 13, 1788. That afternoon, several children were playing outside New York Hospital when they happened to peer into the rooms of Dr. Richard Bayley, an English-trained physician with an ominous reputation.1 Accounts differ, but in the most notorious, one of Bayley’s students, John Hicks, was in the process of dissecting an arm at the time. Upon looking up and seeing the children, Hicks picked up the arm and waved it at them, calling out to one of the boys, “This is your mother’s arm! I just dug it up!”1 The child’s mother had just recently passed away. The terrified boy ran to his father, who exhumed his wife’s coffin with the aid of a number of friends. To their horror, they “discovered that the casket had been opened and the body was no longer in it.”3

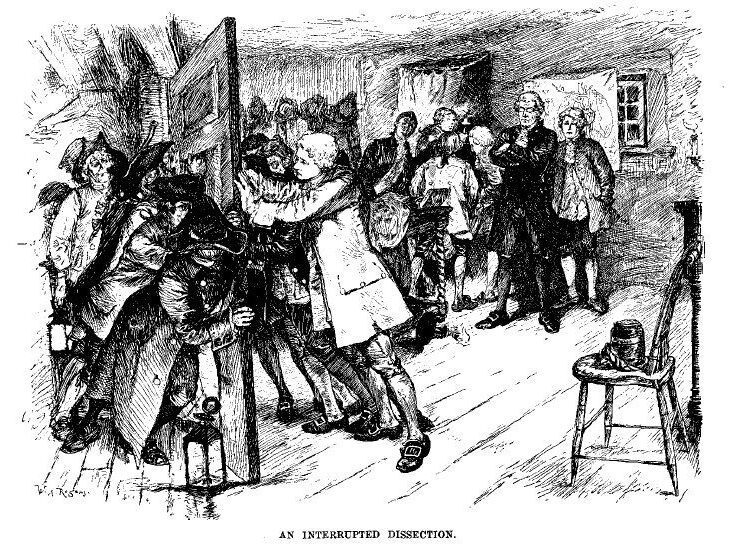

The city’s growing anger finally exploded into fury. “The cry of barbarity was soon spread… the mob raisd [sic] – and the Hospital appartments [sic] were ransacked… Vengeance was denounced against the faculty in general, but more particularly against certain individuals. Not a man of the Profession thought himself safe,” wrote a contemporary.4 A massive mob stormed New York Hospital, destroying every cadaver they found. The few physicians who could not flee in time were bodily seized and dragged out into the street in front of thousands of onlookers. Only timely intervention by the mayor, who had them escorted to the city’s prison for their own protection, saved them.1

The mob soon morphed into a full-blown riot, as physicians and medical students fled for their lives. Physicians were described as having to “slip out of windows, creep behind bean barrels, crawl up chimnies, and hide beneath feather beds” to protect themselves.3 Bayley fled to the jailhouse for his own safety, and as the unrest grew over the next several days, a mob of “5000 frenzied people were massed outside the jailhouse demanding blood.”1 The rioters physically assaulted the jail, attempting to break down the doors—one man was slain while attempting to break through a window.3 It took the direct intervention of the Light Horse Regiment of the colony’s militia3 to break the mob, in a violent melee that may have resulted in up to twenty deaths.1 For the next several days, the military marched through the city in a great show of force to dissuade any more violence, and the furor gradually faded into an exhausted silence.3

Despite its name, not a single physician died during the Doctors’ Riot of 1788.3 However, the ill will from the incident lingered, and in January 1789, the New York State Legislature enacted legislation with harsh punishment—including fines, imprisonment, and whippings—for grave-robbers. For years afterward, the public perception of physicians in New York remained “badly shattered,”3 and medical dissections in the state could only be legally performed on executed criminals. Interestingly, the entire incident also led New York to develop “one of the earliest codes of licensure for the medical profession in the colonies… requiring an apprenticeship with a respectable physician or two years of medical school in addition to a vigorous examination by high government officials.”3 However, this did not dissuade “resurrection men” who took the role medical students had once possessed, controlling “the supply of cadavers for generations.”1

Today, the Doctors’ Riot is an interesting footnote in medical history. However, it remains as a warning to physicians to be aware of and respect the dignity of the greater community. When medical professionals abuse the trust of the community, the consequences may be dire.

References

- De Costa C, Miller F. American resurrection and the 1788 New York doctors’ riot. The Lancet. 2011 Jan 22;377(9762):292-3.

- Swan RJ. Prelude and Aftermath of the Doctors’ Riot of 1788: A Religious Interpretation of White and Black Reaction to Grave Robbing. New York History. 2000 Oct 1;81(4):417-56.

- Swan RJ. Prelude and Aftermath of the Doctors’ Riot of 1788: A Religious Interpretation of White and Black Reaction to Grave Robbing. New York History. 2000 Oct 1;81(4):417-56.

- Bell Jr WJ. Doctors’ riot, New York, 1788. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 1971 Dec;47(12):1501.

DR. MATTHEW TURNER is a current first-year Emergency Medicine resident at Hershey Medical Center. He has long been fascinated by the intersection of medicine and history.

Leave a Reply