Matthew D. Turner

Hershey, Pennsylvania, United States

Jason Sapp

Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington, United States

Introduction

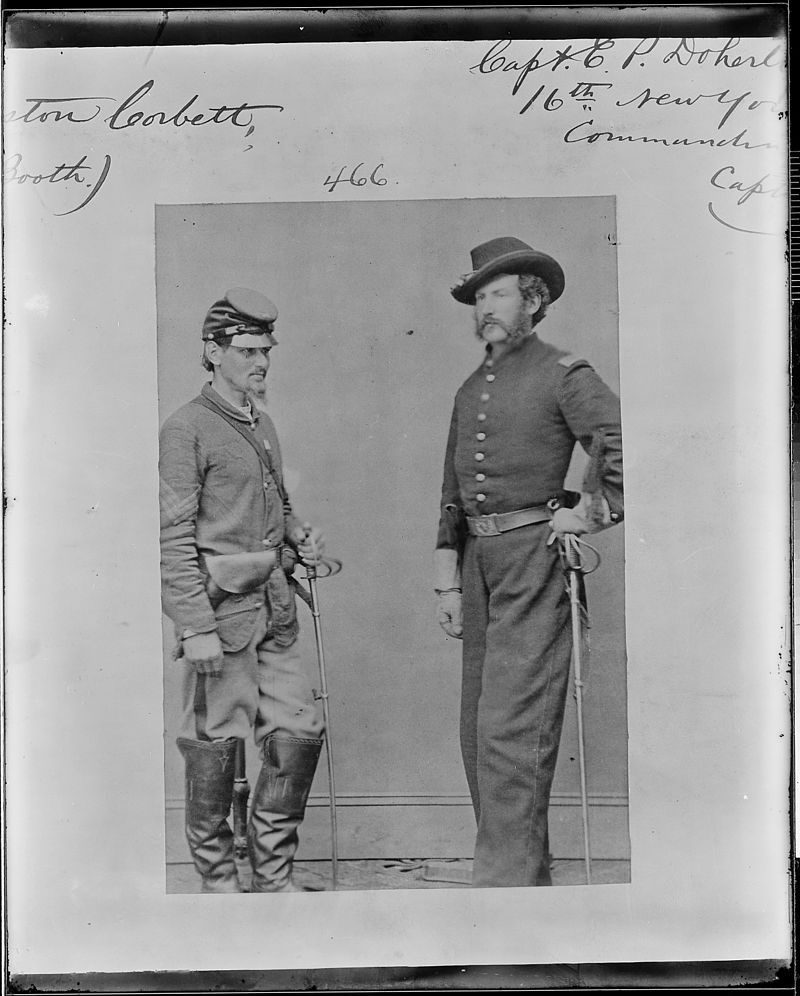

On April 26, 1865, twenty-six soldiers of the 16th New York Cavalry Regiment surrounded a barn on the Garrett farm in Virginia. Hiding within the barn were two refugees, one of them the most wanted man in the United States, and the other his accomplice: the infamous John Wilkes Booth, the man who had shot President Abraham Lincoln fourteen days earlier, and David Herold.1 Herold quickly surrendered, and Lieutenant Colonel Everton Conger, in command of the expedition, gave strict orders that Booth was to be taken alive.2 Among the Union soldiers was Sergeant Boston Corbett, a thirty-two-year-old soldier well known both for his bravery and outspoken tendencies. As the stand-off between the soldiers and the trapped Booth continued, Corbett demanded to be allowed to enter the barn himself—either to drag Booth out or force the assassin to use up his ammunition. His request was denied.3

The soldiers set the barn ablaze in an attempt to flush Booth out, and in the confusion Corbett had a clear line of sight on the assassin.3 Corbett would later make conflicting claims about what happened next, on one occasion claiming that he believed Booth was raising his weapon to fire,2 on another stating, “I think he stooped to pick up something just as I fired,”4 and once claiming that he fired simply because he could no longer stand the “words of scorn and defiance” that Booth spoke.5 The sergeant fired a single shot from his Colt revolver, bringing Booth down with a bullet that shattered his fourth and fifth vertebrae and severed his spinal cord.6 Booth was quickly captured, and within three hours the fugitive was dead from the wound.3 Conger was furious that he had been unable to capture Booth alive and immediately arrested Corbett and sent him to Washington to be court-martialed, stating that he had shot Booth “without order, pretext, or excuse.”2 U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton quickly released the sergeant, stating, “The rebel is dead. The patriot lives—he has spared the country expense, continued excitement and trouble. Discharge the patriot.”2

Corbett would maintain that he had attempted a disabling wound on Booth’s body, but that either a slip in his aim or Booth moving at the moment of the gunshot threw off the intended trajectory of the bullet.6 While the truth is impossible to fully determine, Corbett’s history of chronic mercury poisoning may have played a significant role in the death of Booth—both in Corbett’s decision to disobey orders and open fire, and in his inaccuracy with the shot.

Mercury poisoning

Born in London in 1832 as Thomas H. Corbett, the future soldier immigrated to New York City in 1840. As an adolescent, he began a lifelong career as a hatmaker.6 At the time, the profession involved “felting”—a process where animal pelts were dipped into open vats of mercuric nitrate.7 He continued in this profession until he enlisted in the Union Army in 1861 and resumed his work in the felt hat industry for several years after the war concluded.2 Sayings such as “the mad hatter” and “the hatter’s shakes” were common in the 19th century8 and referred to the plethora of neuropsychiatric symptoms that arose from chronic exposure to inorganic mercury.9

Corbett displayed many of the psychiatric symptoms of chronic mercury poisoning throughout his life. Hatters suffering from chronic mercury poisoning were noted to become quarrelsome, with significantly increased mood lability.10 Further symptoms include depression, hallucinations, paranoia, extreme irritability, insomnia, and fatigue.11 An outspoken man, Corbett became extremely religious after being converted by an evangelical preacher in Boston—even changing his name to mark the occasion.4 He spent much of his time as a fiery street preacher, “whooping and screaming” at otherwise somber prayer meetings,4 and often made a habit of pausing work and forcing his coworkers to kneel in prayer whenever any of them cursed.2 He grew his hair long and parted it down the middle to imitate contemporary depictions of Jesus.3 In 1858, he castrated himself with a pair of scissors in an attempt to ward off sexual temptation.2 While he was renowned for displaying near-suicidal bravery during his time in the Union army—at one point he was said to have killed seven Confederate guerillas before surviving the notorious Andersonville prison camp for four months12—he was often in trouble for disobeying orders. In one episode, the young Private Corbett admonished a colonel for using profane language. His commanding officer was not amused, and Corbett was placed in a guard house as punishment.2 Corbett’s paranoia and explosive temper worsened in the later years of his life, and he often would sleep with a revolver under his pillow.5 When he drew his sidearm on the Kansas legislature in 1887, he was committed to an asylum. He escaped within a week, subsequently vanishing from history.2

Corbett’s history of paranoia, willingness to disregard commands, and hair-trigger tendencies likely played a significant role in his decision to ignore his orders to take Booth alive.2 These tendencies were almost certainly exacerbated by his lifelong exposure to mercury.13

Corbett’s aim was likely affected as well. One of the most prominent symptoms of mercury poisoning is an intention tremor that begins in the fingers and spreads across the body, as well as “psychic disturbances, exaggerated knee jerks, [and] vasomotor disturbances.”14 This, combined with the decrease in visual motor coordination10 and polyneuropathy associated with chronic inorganic mercury exposure,15 may have played a significant role in disturbing Corbett’s shot at the crucial moment. Corbett would himself admit that he was not sure if his aim had slipped or not.6

Conclusion

Sergeant Boston Corbett’s history of behavioral disturbances were likely due to his occupation as a hatter and the chronic exposure to inorganic mercury salts that this profession entailed. The neuropsychiatric sequalae of this exposure may have played a significant role in the death of Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth.

References

- Smith G. American Gothic: The Story of America’s Legendary Theatrical Family – Junius, Edwin, and John Wilkes Booth. New York, Open Road Integrated Media, 2016.

- Johnson BB. Abraham Lincoln and Boston Corbett: With Personal Recollections of Each: John Wilkes Booth and Jefferson Davis: A True Story of Their Capture. Waltham, Massachusetts, 1914.

- Alford T. Fortune’s Fool: The Life of John Wilkes Booth. New York, Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Goodrich T. The Darkest Dawn: Lincoln, Booth, and the Great American Tragedy. Indianapolis, Indiana University Press, 2005.

- Hoover RB, Corbett B. “The slayer of J. Wilkes Booth,” North Am Rev. 1889; 149(394): 382-384.

- Martelle S. The Madman and the Assassin: The Strange Life of Boston Corbett, the Man who Killed John Wilkes Booth. Chicago, Chicago Review Press, 2015.

- Waldron HA. “Did the Mad Hatter have mercury poisoning?” Br Med J. 1983; 287(6409): 1961.

- Wedeen RP. “Were the hatters of New Jersey ‘mad?’” Am J Ind Med. 1989; 16(2): 225-233.

- Ozuah PO. “Mercury poisoning,” Curr Probl Pediatr. 2000; 30(3): 91-99.

- O’Carroll RE, Masterton G, Dougall N, Ebmeier KP, Goodwin GM. “The neuropsychiatric sequelae of mercury poisoning: the Mad Hatter’s disease revisited,” Br J Psychiatry. 1995; 167(1): 95-98.

- Rice KM, Walker EM, Wu M, Gillette C, Blough ER. “Environmental mercury and its toxic effects,” J Prev Med Public Health. 2014; 47(2): 74-83.

- Kauffman, MW. American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies. New York, Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2005.

- Walker DL. Legends and Lies: Great Mysteries of the American West. New York, Tom Doherty Associates, 1997.

- Neal PA. “Mercury poisoning from the public health viewpoint,” Am J Public Health. 1938; 28(8): 907-915.

- Chu CC, Huang CC, Ryu SJ, Wu TN. “Chronic inorganic mercury induced peripheral neuropathy,” Acta Neurol Scand. 2009; 98(6): 461-465.

CAPTAIN MATTHEW TURNER is a current Emergency Medicine intern at Hershey Medical Center in Pennsylvania. He has always been fascinated by the intersection of medicine and history.

COLONEL JASON SAPP is the Program Director of the Transitional Year Program at Madigan Army Medical Center in Washington.

Leave a Reply