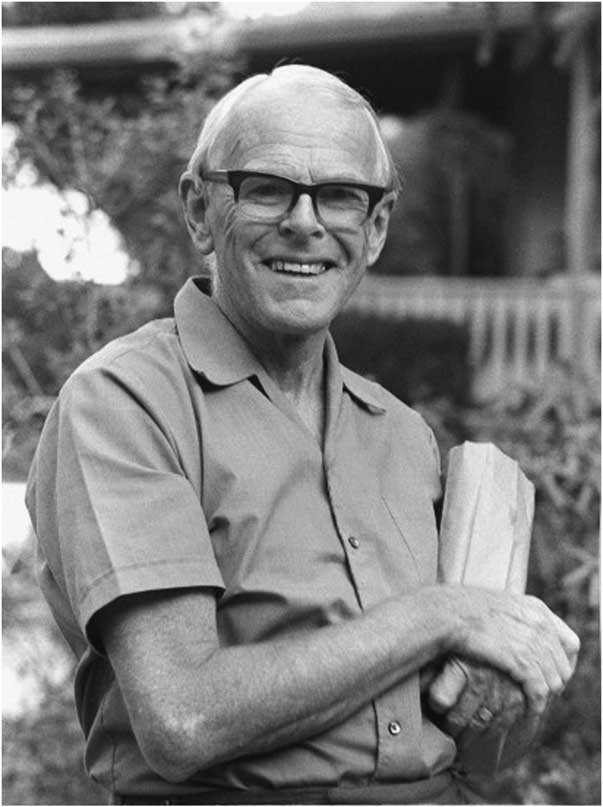

At the age of forty-three, Denis Burkitt acquired eponymous immortality by having an important disease named after him. Born in Northern Ireland in 1911, he received an early education in a highly religious family that emphasized prayer, study of the Bible, and service to others. At age eleven he suffered a serious accident when someone at school threw a stone that broke his glasses, resulting in the loss of one eye. In 1929 he enrolled in the faculty of engineering at Trinity College in Dublin, but after one year switched to medicine and received his medical degree in 1935. He then took resident jobs in Dublin, Chester, and several other towns. In 1938 he passed the specialty surgery FRCS examination. At one time he worked as a ship’s surgeon of a freighter in northeast China. During World War Two he served as a surgeon in the British Army in Africa and parts of Asia. After the war, he decided to work in Africa and eventually became head of the surgical division of a hospital in Kampala, Uganda, where he conducted research and published papers on filariasis, hydroceles, and aspects of artificial limbs.

In 1957 Burkitt was asked to see a five-year-old boy with swellings in the upper and lower jaws. Later he saw another boy with the same disease, but who also had an abdominal tumor. Burkitt studied the hospital’s patient and autopsy records, and he found that these tumors were frequent, could occur without jaw involvement, and even spread to the spinal column causing paraplegia. He realized that the various and seemingly different childhood cancers were all facets of a single, previously unrecognized tumor. On histological examination, all these tumors had the features of a malignant lymphosarcoma. Burkitt published the first reports on this tumor in 1959, describing its histology and atypical distribution. He followed up with epidemiological studies showing that the tumor was common in many parts of Africa, in a belt stretching from south of the Sahara to the east coast to Mozambique. Between 1963 and 1967, he also found that the tumor was temperature- and rainfall-dependent, and that some response could be obtained even with small doses of cytotoxic drugs such as methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, or vincristine. Today, with modern chemotherapy, the long-term survival rates in children range from 60% to 90%. It was also Burkitt’s studies and astute observations that lead to the conclusion that perhaps some 20% of all human cancers are due to viruses, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma, some leukemias, hepatitis B virus in hepatocellular carcinoma, and human papilloma virus.

In 1966, a few years after Ugandan independence, Burkitt left Africa and moved to London. There he met Thomas L. Cleave, author of The Saccharine Disease, postulating that most of the illnesses of modern man were due to eating too much sugar, fat, salt, and processed food. Based on his observation patterns of disease seen in Africa, Burkitt suggested that a low fiber diet played a role in the etiology of hiatus hernia, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, colonic diverticulosis, cancer of the colon, appendicitis, varicose veins, and hemorrhoids, all of which were uncommon in the high fiber eating African natives. He thus joined a group of individuals who were fascinated by fiber and became tireless in advocating its importance in western diet. Although their work has been criticized as being based on anecdote rather than on detailed epidemiological evidence and not comparing like with like, it has served to draw attention to the importance of insufficient fiber and roughage in preventing constipation, hemorrhoids, and diverticulitis. Although some of Burkitt’s theories have been challenged, his legacy lives on, paving the way for a greater understanding of the relationship between diet, health, and disease.

Further reading

- Epstein A, Eastwood MA. Denis Parsons Burkitt. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, Nov 1995;41:88-102.

Leave a Reply