Florence Gelo

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

When teaching medical students, I often incorporate works of art to introduce students to social determinants of health and to gain insight into the nature and importance of whole person care, the physical, behavioral, emotional, social, and spiritual factors that contribute to well-being.

Social determinants of health (SDH) are factors impacting a person’s health. SDH contribute to quality of life and well-being in both positive and negative ways. The World Health Organization defines SDH as the “conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, along with the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.”1 SDH reveal root causes that create health disparities, inequalities, and contribute to disease. These factors include economic instability, lack of access to education, limited language skills, inability to read and write, inadequate access to housing, health care and nutritious food, lack of community connections, and unsafe environments. Structural barriers for achieving quality of life for all include racism, sexism, heterosexism, ableism, ageism, and more.

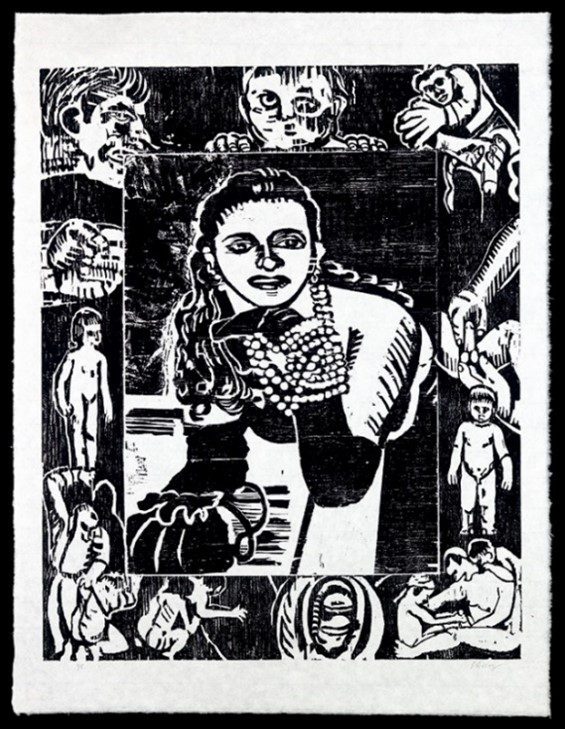

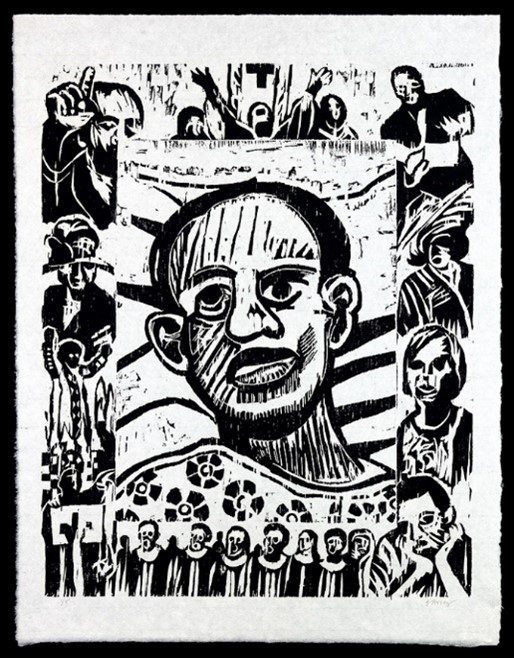

Among the artworks that illustrate the social determinants of health and that students view and discuss are two works by Eric Avery, in a series of six woodcut prints entitled The New Face of AIDS – Patient Portraits in Frames of HIV Risk, 1994–2011. Avery’s images in content and composition are ideal as teaching tools. Each provides a visual case example to expand students’ understanding of social determinants of health and health disparities, most notably those influenced by structural and environmental life conditions. In each print, a central portrait is framed by a series of biographical images of people, experiences, and memories illustrating the cumulative factors impacting the person’s well-being and contributing to trauma.

Eric Avery is an artist who became a psychiatrist. His medical training and humanitarian concerns led him to devote the last twenty years of his practice to the care of patients with AIDS. Working as a psychiatrist on HIV wards, he listened to patients’ stories and asked for permission to draw their portraits. Avery stated his purpose during a conversation: “You’re not just making art. You are making art in a very particular way.” He explained that his art’s purpose was to bear witness, “acknowledging the existence of these people, whoever those people are.” In this way, Avery strived to “open up the world of AIDS” (Eric Avery, personal communication, December 21, 2022) and advocate for those rendered invisible by society.

The Four Forms of Childhood Abuse (Figure 1) highlights the medical, psychological, behavioral, cognitive, and spiritual consequences of physical abuse that can result in trauma. A second print, Sunday Morning (Figure 2), highlights the traumatic impact of societal attitudes and the consequent “othering” and dehumanization of individuals, based on the life experiences of Avery’s many AIDS patients.

In the center of the image in Figure 1, The Four Forms of Childhood Abuse, is Sophie, a transgender sex worker. Upon meeting the artist, Sophie was homeless, addicted to cocaine, and living with AIDS. Sophie, who serves as a prototype for the many, is framed by images of the types of abuses that Avery found “ubiquitous” in people living with AIDS. The abuses pictured are verbal, physical, emotional, and sexual, all significant factors that contributed to HIV risk behaviors and often resulted in post-traumatic stress disorder.

In the image in the upper left-hand corner, a verbally abusive man grits his teeth; top center is a young child who has been physically abused, as evidenced by his bruised face and misshapen eye. In the upper right corner, an adult is engaged in the criminal act of exposing his penis and reaching for a child. The remaining narrative scenes highlight nonconsensual, sexual touching between a child and adult. The next five images depict children being sexually abused in various ways. In one of them is an image based on a forensic photograph examining a perforated hymen of a little girl, part of the examination of children who have been raped.

In the center of Sunday Morning (Figure 2) is a young African American who told Avery a story about sitting in the church pew during a Sunday service. The preacher pointed to him and publicly exposed him as a gay man with HIV, shaming him in front of a congregation of those who, traditionally, would have been a source of support for ill members like him. Instead, he came to be shunned.

The print visualizes this condemning community. When looking at Sunday Morning, the young man in the center is in his hospital bed, wearing the common patterned hospital gown. Images of church life surround him. The image on the top left shows a preacher raising his finger and pointing to the young man, making him an object of scorn, mockery, and disdain. Above the central figure, the preacher, standing in the pulpit, blames, shames, and condemns him. Continuing clockwise, believers are seen praising God; a man holding a Bible; a woman with her large and impressive Sunday church hat; another woman, maybe his mother (Avery suggests “mother” based on the young man’s story); the choir and another person, arms raised in praise.

The Christian church in the African American community has historically been the source of strength, spiritual comfort, support, connection, and moral guidance. Belonging can promote self-esteem and confidence, attributes that would counter the emotional and psychological ravages of living with HIV. In being shunned, this young man was denied that healing.

In these woodcut prints, Avery is telling viewers something important about human vulnerability and harm to hearts and psyches. His images depict myriad acts of violence and aggression. Each figure is surrounded by people or events that negatively impact health and quality of life. Each specific situation allows for reflection and discussion with students about the immediate and long-term impact of traumatic events on persons, families, and communities.

When teaching medical students, I ask them to become aware of and examine the multiple and intersecting circumstances of a patient’s life. The goal is to teach comprehensive and compassionate assessment, diagnosis, and treatment, which requires attention to the broader societal and systemic factors that contribute to health and well-being. If a provider of medical care does not understand that disease is not the only issue, is unaware of the sources of physical, emotional, psychological, and spiritual distress and how they exist in dynamic interaction with other aspects of their patients’ lives, then attempts to provide holistic treatment for mind, body, and spirit are compromised.

Sophie in the first print (Figure 1), and the gay man in the second (Figure 2), are people in our culture who are often marginalized, rendered invisible, and systematically excluded from meaningful participation in society. They are blamed for their life circumstances: the young man, for being gay and infected with HIV; Sophie, for being homeless, a sex worker, a drug user, and infected with HIV. From society’s point of view, they are damaged goods, and are discarded.

Viewing these prints can help students identify and reflect on personal barriers that could impede successful treatment. Students can witness how they tend to view others and if they see them as “different” or of lesser value. When clinicians attempt to form therapeutic relationships with patients, awareness of personal biases that create barriers to developing authentic relationships is essential. Unintentionally imposing personal bias and prejudice on patients disempowers the very people clinicians want to heal. Students need to develop the skill to understand the “other” and to be curious about the life experiences that have formed the client or patient. Effective treatment is predicated on this skill.

Using the visual arts in teaching is an ideal method to begin to create awareness and curiosity about the lives of others. Through close looking, self-reflection, and small-group discussion, students can examine their thoughts, feelings, and perceptions as they interact with one another while engaged in a common task of looking at art, as they learn about life’s challenges and the injustice that fuels human ruin.

This teaching methodology can encourage students to identify what they love and fear and to explore thoughts and emotions that they may not yet be ready to acknowledge or share. The visual arts can cultivate openness to learning, empathic concern, and sensitivity to others. At their best, works of art can speak to us in ways that words alone cannot, and in so doing, allow us to find ways to speak to and care for others.

References

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. Retrieved May 1, 2023, at https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1.

FLORENCE GELO is a medical humanities and behavioral science educator. She directed and produced “The HeART of Empathy: Using the Visual Arts in Medical Education,” and uses the visual arts as a teaching tool to enhance clinical skills. She has published numerous articles in professional journals about illness, death and dying. A recent project used images of narrative paintings to assist hospice patients to speak about the day-to-day realities of living while dying.

Leave a Reply