Adil Menon

Chicago, Illinois, United States

The USPHS Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male is United States medical history’s most tragic example of the road to Hell being paved with good intentions. In the early 20th century, the Public Health Service and the Rosenwald Fund looked to Alabama’s Maycomb County and found a community much in need. 35% of the county’s 27,000 impoverished sharecroppers were found infected with syphilis, offering a seemingly perfect location for researchers to conduct a test case for a nationwide syphilis treatment program. The end of Rosenwald funding took with it these lofty ambitions, and in the early 1930s, Drs. Taliaferro Clark, head of the PHS’s section on venereal disease, and Raymond H. Vonderlehr, the onsite director, decided to demonstrate the need for a treatment program by leaving their subject’s infections untreated. Vonderlehr decided to gain the “consent” of the men for spinal taps needed to monitor neurosyphilis by depicting the diagnostic tests as a “special free treatment.” Ultimately, the study would go on for 40 years, study roughly 600 subjects, kill 30, and infect hundreds, even though efficacious treatments for syphilis had existed since 1945.

The Tuskegee trial and its end represented a seminal moment in the history of bioethics as outrage united many. Yet while the study ended over 40 years ago, the fear of being exploited as “guinea pigs” remains a recurring refrain in the African-American community. This trepidation not only leads community members to eschew potentially lifesaving experimental treatments, but has also given rise to fears of intentional infection with an AIDS-like virus and of exposure to harmful substances such as Agent Orange while serving as research participants. When the benefits of the potential research are explicitly mentioned to attempt to increase minority participation, researchers often find themselves faced with the question “given the way brothers [blacks] are treated, how it is going to help me?” Even informed consent continues to fail the very population it was meant to help. In Corbie et al’s study of African American views on taking part in research, many participants believed that “if you give consent, then you don’t have any legal rights,” the opposite of what is meant to be achieved. It is clear that African-American trepidation on participating in research continues to be a deeply nuanced and multifaceted issue.

As we consider what shapes the African-American community’s views on participation in clinical research, it becomes increasingly clear that the Tuskegee Trial simply serves as a name around which a history of exploitation has coalesced, demonstrated when individuals were queried about the event; in studies by Paul et al, several African Americans asserted that the Tuskegee participants were actively injected with syphilis, and saw the study as evidence for “how effectively the government could use science to exterminate blacks.” In light of these and similar responses, the legacy of Tuskegee is not the cause of the lack of African-American research participation, but rather the symptom of mistrust reinforced by a medical establishment that dismissed such fears as lunacy while failing to “hear the fears of the people whose faith had been damaged.”

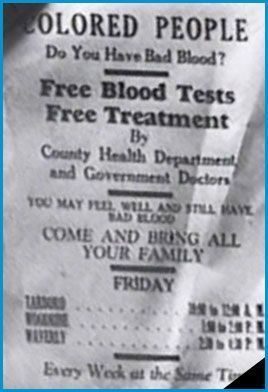

The emphasis placed on Tuskegee and its legacy additionally reinforces several perceptions that engendered it, including the doctors’ assertion (which allowed the experiment to continue for 40 years) that the patients had no desire for treatment, despite the doctors advertising the experiment as follows:

Colored People

Do you have bad blood?

Free Blood Tests

Free Treatment

It is clear that even the doctors themselves did not believe their own excuse but rather committed themselves to a myth of their own creation out of convenience. Ironically, the Tuskegee study has birthed an almost identical myth in our present era. Researchers for a more recent prostate cancer study were able to recruit only one African-American participant despite aiming for 20% minority participation; many of them asserted that as a result of Tuskegee, recruiting blacks would be so “difficult” and “impossible” that the results would not be worth the effort. As Dr. Otis Browley, an African American oncologist, asserts, “researchers use Tuskegee as an excuse for laziness.” Rather than making the effort to recruit more African-American researchers or go into the community to spread information about the benefits of participating in experimental research, it is far simpler to blame the legacy of Tuskegee. It is cheaper as well. The recruitment of African-American subjects is time consuming and expensive, especially as researchers must often make arrangements for childcare and transportation: details many are unwilling to bother with.

The Tuskegee Syphilis trial provides a convenient myth for failing to address the legitimate fears of the African American community. Informed consent continues to be seen by those it is meant to protect as a mechanism of exploitation. Researchers have kept the myth of African Americans not wanting treatment alive and continue to disincentivize minorities as participants in clinical research, leaving effective progress elusive.

References

- About Us. (2014, January 1). Retrieved December 8, 2014, from http://www.tuskegee.edu/about_us/centers_of_excellence/bioethics_center/about_the_usphs_syphilis_study.aspx

- Carter, R., & Mendis, K. (2002). Evolutionary And Historical Aspects Of The Burden Of Malaria. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 564-594. Retrieved December 7, 2014, from Pubmed.

- Corbie-Smith, G., Thomas, S., Williams, M., & Moody-Ayers, S. (1999). Attitudes and beliefs of african americans toward participation in medical research. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 537-546.

- Gamble, V. (1997). Under the Shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and Health Care. American Journal of Public Health, 87(11), 1773-1776.

- Gibson, G. (2013). SICKLE CELL DISEASE: THE ULTIMATE HEALTH DISPARITY. 1-20.

- Gray, F. (1998). The Tuskegee Syphilis Study the real story and beyond. Montgomery, Ala.: NewSouth Books.

- Jones, J. (1993). Bad blood: The Tuskegee syphilis experiment (New and expanded ed.). New York: Free Press ;.

- Levinson, D. (2013). CHALLENGES TO FDA’S ABILITY TO MONITOR AND INSPECT FOREIGN CLINICAL TRIALS.

- Mann, C. (2011). 1493: Uncovering the new world Columbus created. New York: Knopf.

- Paul, C., & Brookes, B. (2015). The rationalization of unethical research: Revisionist accounts of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and the New Zealand “Unfortunate experiment.” American Journal of Public Health, 105(10). https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2015.302720

- Reverby, S. (2000). Tuskegee’s truths: Rethinking the Tuskegee syphilis study. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- The Reluctance of Black People to Participate in Clinical Medical Research. (1997). The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, 17, 33-34. Retrieved November 28, 2014, from JSTOR.

- The Rise of Unregulated Drug Trials in South America. (2011, September 22). Retrieved December 8, 2014, from http://pulitzercenter.org/reporting/central-america-drug-clinical-trial-federal-regulations

- U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. (2013, September 24). Retrieved December 8, 2014, from http://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm

- Washington, H. (2006). Medical apartheid: The dark history of medical experimentation on Black Americans from colonial times to the present. New York: Doubleday.

DR. ADIL MENON, MD, is a third-year Clinical Pathology Resident at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. His written work may be found in journals including Hektoen International, the Harvard Medical School Bioethics Journal, The Pathologist, JAMA Cardiology, and the Journal of Clinical Tuberculosis and Other Mycobacterial Diseases, with additional work found on the Student Doctor Network and the Merck Manuals Med Student Stories. His professional interests include microbiology, medical education, and global health equity and infrastructure.

Leave a Reply