Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

“This Frenchman comes to the assistance of foreign Jews he does not even know.”

– Eryane Kahan, a Romanian Jew living in Paris, at Petiot’s trial

“He lured the desperate, the frightened…to his lair…and murdered them.”

– Pierre Véron, a plaintiff’s attorney at Petiot’s trial

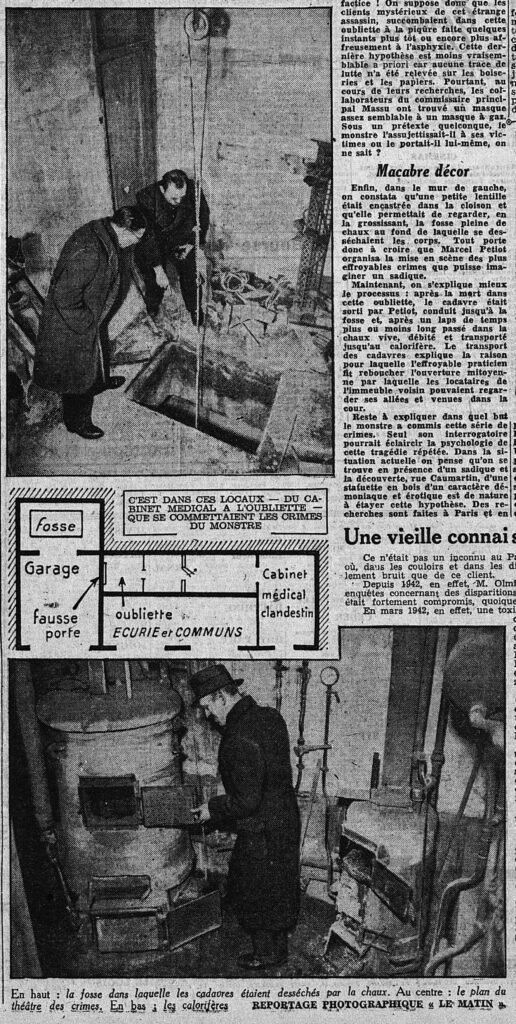

In March 1944, in the 16th arondissement of Nazi-occupied Paris, neighbors saw and smelled foul-smelling smoke leaving the chimney of an unoccupied house. The police entered the house and found human body parts burning in two coal-fired ovens, and human heads skillfully dissected so that the faces were removed. In addition, they found hands with the fingertips removed, another way of making identification impossible. There were also bodies in a pit of quicklime (calcium oxide), a substance believed to accelerate decomposition. The house belonged to Dr. Marcel Petiot.

Marcel Petiot had an eventful childhood. At age three he tried to drown a pet cat, and finally smothered it. He had nocturnal and daytime enuresis (urinary incontinence) and encopresis (stool incontinence) until age eleven. A “triad of sociopathy” was described by New Zealand psychiatrist John Macdonald in 1963.1 It consisted of cruelty to animals, fire setting, and enuresis. Any two of these three behaviors, according to Macdonald, were associated with later homicidal behavior. Subsequent research cast much doubt on the validity of this idea. The concept of antisocial personality disorder2 is characterized by childhood animal cruelty and enuresis or encopresis. Such individuals, as adults, are described as manipulative liars. They may also be involved in violent crimes. Young Marcel was often truant from school,tried to steal mail from public letterboxes, and was expelled from school and was seen by a psychologist who diagnosed him as having “mental problems.” He was sent to a boarding school, from which he was also expelled.

He did not wait to be mobilized in World War One and enlisted in 1916. He was injured in the foot by shrapnel and was also diagnosed with “shell shock.” (This World War One diagnosis became “battle fatigue” in World War Two, and post-traumatic stress disorder in combatants of later wars.) Placed in a military mental hospital, he was caught stealing hospital blankets and objects from fellow patients and was jailed. He was diagnosed as suffering from “depression, melancholia, obsessions, phobias, and neurasthenia.” He was sent back to active duty in 1919, and was hospitalized again in 1920.

In 1922, he visited his two aunts (who had raised him, for the most part) and told them that he had studied medicine in Paris. He showed them a letter from the Faculty of Medicine stating that his thesis was satisfactory, and that he was a physician. By 1923, he was a physician in a small French village. In 1926, his live-in maid, who was also his pregnant girlfriend, was found dead (and decapitated) in a nearby river. Petiot was later elected mayor of this village. He was suspected of the theft of gasoline from a depot, as well as murdering a bar owner who spread stories about him. He was suspected of performing abortions and of killing a patient with a heroin overdose. He was found guilty only of tax fraud.

After the occupation of France, the Gestapo heard rumors that Petiot (alias “Dr. Eugène”) was helping Jews leave the country. He was imprisoned for eight months and released when no evidence was found of this “crime.” In 1944, the police found dozens of suitcases filled with clothing, furs, and valuables in Petiot’s house. He had told his victims that his connection at the Argentine Embassy could help smuggle people out of France. Most of these people were Jews, and others were petty criminals or prostitutes. They paid a fee “requested by the Argentine diplomat,” and were instructed to bring all their money with them to start a new life in South America. He told them that they needed a vaccination to enter Argentina. This “vaccination” killed them, and he disposed of the bodies by burning or dumping them in the Seine. Prosecutors were certain he had killed at least twenty-seven people in Paris.

Petiot maintained that he killed Germans, either civilians or members of the Wehrmacht, or French collaborators. This was, he said, one of his functions as a member of the Resistance. None of this was supported by evidence. After a sixteen-day trial, he was executed in 1946. He committed his crimes in a city under enemy occupation. Parisians knew that the French police worked under Gestapo control, and were afraid of dealing with the police. People who disappeared—ostensibly to Buenos Aires, but were killed and never heard from—were not reported to the police. It seems, in addition, that there was no system which verified the credentials of a “physician.”

Note

Unless otherwise noted, the information in this article comes from Marilyn Thomlins, Die in Paris. The True Story of France’s Most Notorious Serial Killer (London: Raven Crest Books, 2013)—an interesting, well-researched story about one of the far-too-many medical serial killers.

References

- “Macdonald triad.” Wikipedia.

- “Antisocial personality disorder.” Wikipedia.

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Leave a Reply