Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

Ancient Egyptian medicine was based on religion, magic, and specific conceptions of human anatomy and physiology. The human body was believed to contain twenty-two “channels” (called metu) that carried blood, air, water, urine, mucus, semen, and bodily waste. These channels were arteries, veins, tendons, and nerves.1 A blockage in any channel could allow a toxin (wekhedu), originating in the intestine, to produce aging, disease, and death.2 All vessels came from the heart and had “a second rallying point around the anus.”3 Heynick writes that the Egyptians had an “obsession with the anus.”4

Both women and men were physicians in ancient Egypt. The physician (a swnw, pronounced “soonoo”) was typically a specialist, concerned with either diseases of the eye, the gastrointestinal tract, or the anus.5 We have learned about ancient Egyptian medicine from papyri written by and for physicians. The 20 meter long Ebers Papyrus (from about 1550 BC) describes hundreds of prescriptions, one-fourth of which were for gastrointestinal problems.6

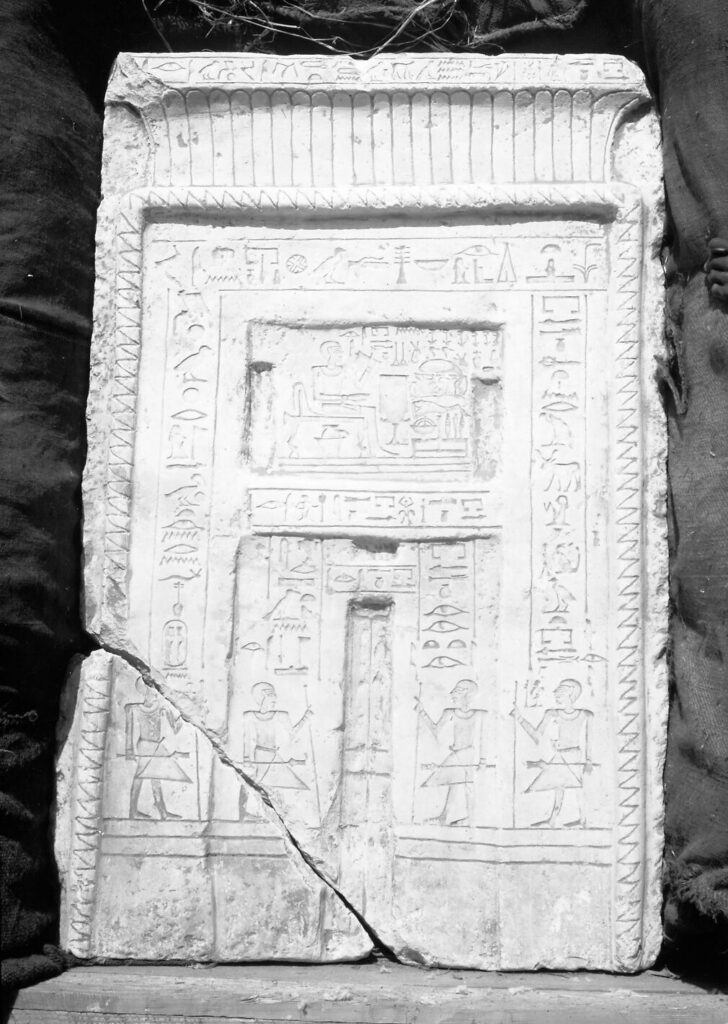

In the Sixth Dynasty (2345–2181 BC), the physician Iry (or Ir-en-akhty) was awarded the exalted position of “Shepherd of the King’s Rectum” (also translated as “Keeper of the King’s Rectum,”7,8 “Guardian of the Royal Bowel Movement,”9 “Doctor to the King’s Belly,”10 or “Shepherd of the King’s Anus”11). The pharaoh was a god, and attending to his medical care was a great honor. One of the treatments given the pharaoh was an enema (a colonic lavage) via a golden cannula inserted per rectum.12 The lavage fluids could have been water, milk, beer, or wine, each mixed with honey and medicinal additives.13 The goal was to prevent toxin accumulation. Enemas were administered on three consecutive days each month. It is claimed that the Egyptians invented the enema after watching the Nile ibis insert its beak into its anus and inject water.

Schistosomiasis, a parasitic infestation, has been suggested as a possible reason for the colonic “obsession” of ancient Egypt. The parasite, a flatworm, spends part of its life cycle in freshwater snails. An immature form of the worm leaves the snail and enters humans through the skin when the victim washes clothes, bathes, works, or walks in the water. The worms reproduce in human veins, often in veins surrounding the rectum or bladder. When the eggs are ready to leave the body—via the bladder or rectum—they burrow from their venous home through the walls of the bladder or rectum. Sometimes they do not make it through to the lumen (the hollow part of the organ in question) but get stuck in the wall. This will cause abdominal pain, mucus and blood in the stool, diarrhea, and abdominal distension. An inflammatory immune response will produce further complications, including colonic strictures or bowel obstruction.14 Mummies from about 1000 BC have been found to contain mummified schistosomes.15 Worldwide, almost 800 million people are at risk for schistosomiasis and more than 250 million are infected. Egypt is now considered by the World Health Organization to be a “low prevalence” (i.e., less than 10% prevalence) area for the condition.16

Acknowledgment

I thank Åke Engsheden, Egyptologist, for corrections and helpful comments.

References

- Hedvig Györy. “Medicine in ancient Egypt.” In G. Murdock, Theories of Illness (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1980).

- Tashia Dare. “Chapter 3: Ancient Egyptian medicine.” In Danielle Skjelver et al (eds.), History of Applied Science and Technology: An Open Access Textbook (Grand Forks, ND: The Digital Press @ UND, 2021). https://press.rebus.community/historyoftech/chapter/ancient-egyptian-medicine/.

- Guido Manjo. The Healing Hand: Man and Wound in the Ancient World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1975.

- Frank Heynick. Jews and Medicine: An Epic Saga. Hoboken, NJ: Ktav Publishing House, Inc., 2002.

- JF Nunn. “The doctor in ancient Egypt.” Accessed via Simon Rupf’s Ansichtssache. https://simon.rupf.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/The-doctor-in-Ancient-Egypt-J.F.-Nunn.pdf.

- Dare, “Ancient Egyptian medicine.”

- Heynick, Jews and Medicine.

- Albert Lyons and Joseph Petrucelli. Medicine: An Illustrated History. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1978.

- R. Sullivan. “A brief journey into medical care and disease in ancient Egypt.” JR Soc Med, 88(3), 1995.

- Sibylle Scholtz. “2400 BC, Egypt: Iry, the first identified eye doctor by stele interpretation.” In Sibylle Scholtz et al. (eds), Curiosities in Medicine (Heidelberg: Springer, 2012).

- Scholtz, “Iry.”

- “Strange jobs of history: ‘Guardian of the anus’ in ancient Egypt.” Weird History Facts, June 8, 2022. https://weird-history-facts.com/guardian-of-the-anus/.

- Hanem Khater. “Introductory chapter: Back to the future—Solutions for parasitic problems as old as the pyramids.” In Hanem Kater et al (eds.), Natural Remedies in the Fight Against Parasites (IntechOpen, 2017). https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/54617.

- “Schistosomiasis.” Wikipedia.

- Robert Desowitz. New Guinea Tapeworms and Jewish Grandmothers. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1987.

- Donald McManus et al. “Schistosomiasis.” Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 4, 2018.

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Leave a Reply