Diego Andrade

Stalin Santiago Celi

Quito, Ecuador

Quinine is considered to be one of the most important medical discoveries historically, as it marked the first successful use of a chemical compound to treat malaria. Malaria is an acute febrile disease caused by Plasmodium parasites, which are transmitted through the bites of female Anopheles mosquitoes.1 Without treatment, the infection can progress to serious disease and may be life-threatening. Five species of Plasmodium are known to cause malaria in humans. Two of them, P. falciparum and P. vivax, pose the greatest threat. P. falciparum is the deadliest and most common malaria parasite in Africa, while P. Vivax dominates in tropical climates in other parts of the world.1 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2021 almost half of the world’s population was at risk of contracting the disease, with children under five, pregnant women, people with immunosuppression, migrant workers, and mobile populations being at highest risk of contracting malaria and developing severe disease.1 Worldwide, there were 247 million cases of malaria and 619,000 deaths in 2021.2

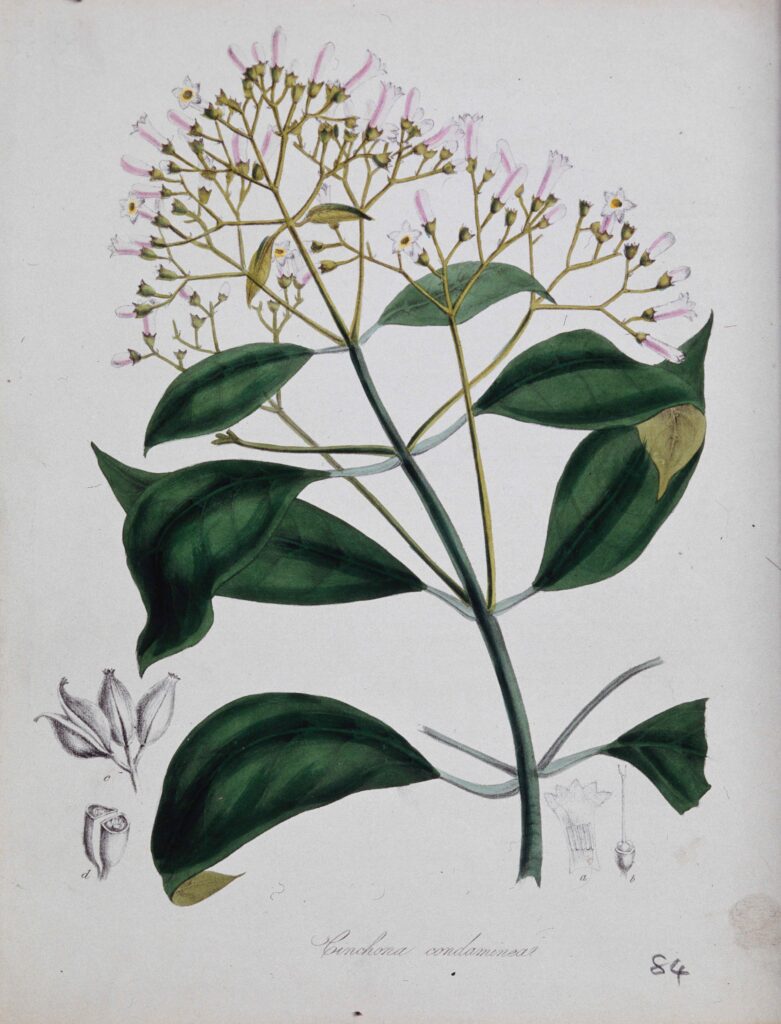

Quinine was the mainstay of malaria treatment until the 1920s, when more effective synthetic antimalarials became available. Even at therapeutic doses, quinine is known to cause a collection of adverse effects known as cinchonism, which includes tinnitus, reversible hearing loss, confusion, diarrhea, visual disturbances,3 ataxia, tremor, and other symptoms.4 The Cinchona botanical genus, to which the Quina or cascarilla tree belongs, is native to mountainous areas from Colombia to Bolivia.

According to the testimony of a Spanish Jesuit priest, Father Juan López, a seventeenth-century indigenous chief named Pedro Leiva, originally from present-day Loja in Ecuador, is credited with discovering the antimalarial effects of the bark of the cinchona tree (Cinchona Officinalis).5 He began to administer the pulverized bark of the tree to people with malaria symptoms. This practice was then taken up by the magistrate of Loja, Juan López de Cañizares, who was cured himself by Leiva’s treatment.6 This news spread to Peru, where the Countess Francisca Henríquez de Ribera, wife of the viceroy of Peru, was seriously ill with malaria.6 The bark was sent to Peru and the countess was cured. She then traveled back to Spain with the bark, introducing quinine to Europe in 1638.7 In 1742, the botanist Carl Linnaeus named the tree “Cinchona” in honor of the Countess of “Chinchona” Francisca Henríquez de Ribera,8 thus providing the botanical classification and scientific nomenclature to the genus.

In the 1660s, the use of cinchona bark became known in England and Denmark.9 In the 18th century, botanical expeditions to South America were organized by the Netherlands and England to acquire cinchona seeds and plants that could be cultivated in the colonies.9 In the British Empire, the Quina tree was introduced to India, Burma, Ceylon, Sudan, Jamaica, Trinidad, Mauritius, Australia, and New Zealand. Outside of the British Empire, it was grown in Java, West and East Africa, the Fiji Islands, Madagascar, and other places. Java, India, and Ceylon contributed most to the world supply of bark.9 Before 1820, the processing of bark as an antimalarial treatment began with drying and grinding it into a fine powder that was then mixed into a liquid (usually wine) before drinking.7 Isolation of the alkaloid from the bark was carried out in 1820 by Pierre Pelletier and Joseph Caventou, establishing purified quinine as a treatment for malaria.10,11 Dutch plantations and the quinine industry dominated the market9 and generated tremendous economic profits throughout the world. However, the global quinine supply ended with the Japanese occupation of Indonesia in 1942.9 As synthetic antimalarials were developed over time, chloroquine became the drug of choice. Yet intensive use produced drug resistance, which led to the development of other drugs such as artemisinin.9

Quinine represented a substance of great importance for global malaria treatment for decades. Andean ancestral cultures played a critical role in its discovery and use. Since malaria is now a preventable and treatable disease, there should be a global focus on efforts to reduce the burden of morbidity and mortality, with the ultimate goal of eradication.

Dedication

In memory of Antonio Crespo Burgos, MD, physician, researcher, and former director of the National Museum of Medicine of Ecuador.

References

- World Health Organization. “Malaria.” March 29, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria.

- World Health Organization. “WHO guidelines for malaria, 25 November 2022.” November 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/364714.

- Bykowski A, Logan TD. “Cinchonism.” StatPearls. Feb 19, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559319/.

- Zou, L, et al. “The Effects of Quinine on Neurophysiological Properties of Dopaminergic Neurons.” Neurotox Res 34. no 1 (2018):62-73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12640-017-9855-1.

- Jaramillo Alvarado, P. History of Loja and its province. Quito: Ed. House of Ecuadorian Culture, 1955.

- Revelo Rosero, J. “The Aboriginal Doctor Pedro Leiva and Quina.” In The Condor, the Snake and the Hummingbird. PAHO/OMS and Public Health in Ecuador of the Century XX, 40-2. Quito, Ecuador: Consejo Editorial, 2002.

- Achan, J, et al. “Quinine, an Old Anti-Malarial Drug in a Modern World: Role in the Treatment of Malaria.” Malaria Journal 10, no. 144 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-10-144.

- Permin, H, et al. “On the History of Cinchona Bark in the Treatment of Malaria.” Dansk Medicinhistorisk Arbog 44, (2016): 9-30. PMID: 29737660.

- Cambridge University Library. “Products of the Empire: Cinchona: A short history”. Accessed December 7, 2022. https://www.lib.cam.ac.uk/rcs/projects-exhibitions/products-empire-cinchona-short-history.

- Haas, LF. “Pierre Joseph Pelletier (1788-1842) and Jean Bienaime Caventou (1795-1887).” Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 57, no. 11 (1994): 1333. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.11.1333.

- Karamanou, M, et al. “Isolating Colchicine in 19th Century: An Old Drug Revisited.” Curr Pharm Des 24, no. 6, (2018):654-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/1381612824666180115105850.

DIEGO ANDRADE is a physician. Art plays a vital and transcendent role in his life. He has published one book and served as co-author of another. In addition, he has authored scientific articles and those of historical and medical interest.

STALIN SANTIAGO CELI is a physician, post graduate student (Radiology), and co-author of a book on the history of radiology, as well as of many scientific articles.

Leave a Reply