Stephen Kent

Warrington, United Kingdom

Introduction

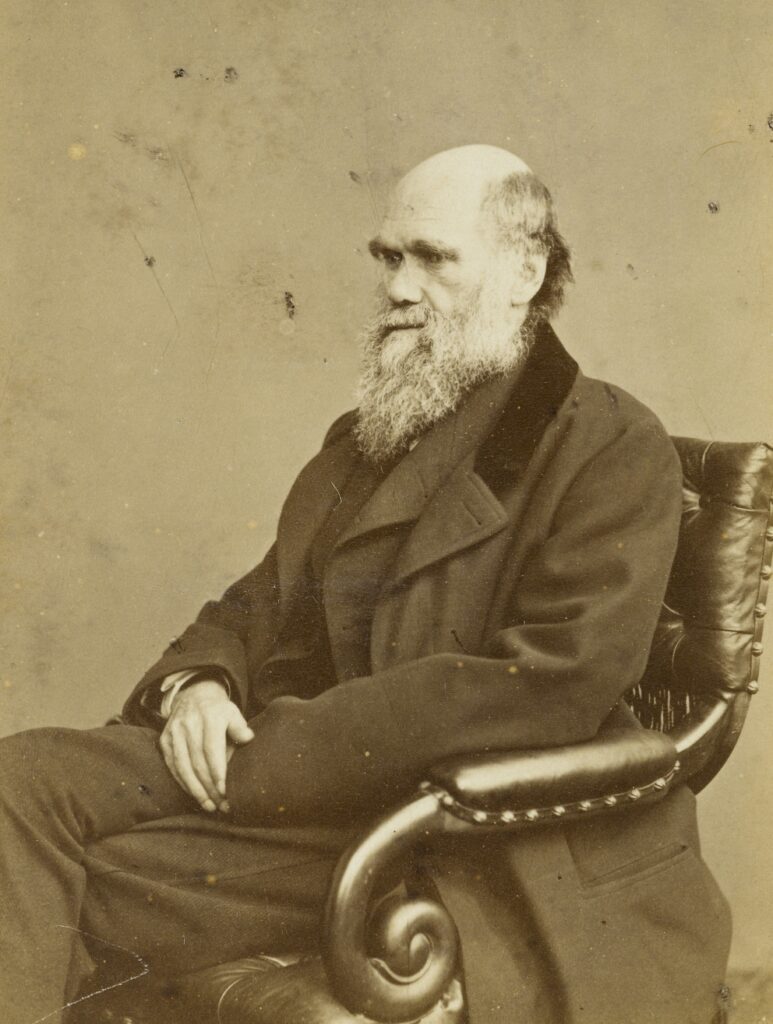

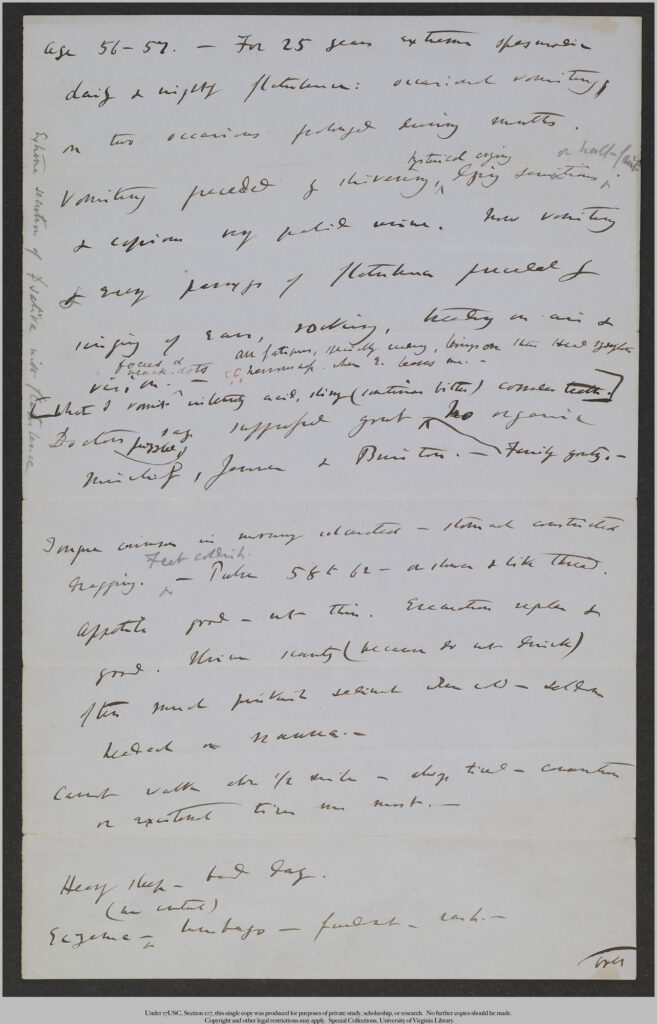

Charles Darwin has been the subject of intense study over the last 140 years, not only because of his publication of The Origin of Species through Natural Selection, but also because his extensive correspondence gives a clear insight into the character of the man himself. One of his preoccupations in middle age was keeping a daily health diary. This has been the main source material for publications attempting to diagnose the cause of his chronic symptoms.

Darwin was born in Shrewsbury, England in 1809, the fifth child of a wealthy general practitioner. He enrolled as a student at Edinburgh Medical School (1825–1827) but abandoned the course after two years, allegedly because he could not stand watching operations in the days before general anesthesia.1 After three years of enjoying life at Christ’s College Cambridge, he was fortunate to obtain a place as a gentleman naturalist on HMS Beagle’s round-the-world survey expedition. Writing up his geological and biological findings (1835–1842) established his reputation as a naturalist, and he was able to live a quiet life in the Kent countryside, write thousands of letters, have a large family, and enjoy the attentions of a devoted wife.

Unfortunately, his chronic, recurrent illness gave him the distressing symptoms of vomiting, flatulence, weakness, and many other minor symptoms. He consulted the most eminent doctors of his day, but no definitive diagnosis was made. He took a multitude of medications, attended fashionable “health spas,” and wrote to friends constantly about his poor health.2 Since his death in 1882, many doctors have been fascinated by possible causes of his chronic illness. Although a conclusive diagnosis is unlikely to be proven, many authors have confidently proposed diagnoses. The fascination of discovering the truth has even provoked one author to suggest to the authorities at Westminster Abbey that Darwin’s remains should be exhumed for examination.3 Many authors are frustrated that modern diagnostic tests cannot be used, but one ingenious researcher has obtained hairs from Darwin’s beard and performed DNA analyses to speculate on his illness.4

This paper examines the professional opinion of doctors that Darwin consulted and the differential diagnoses and managements proposed by physicians in the UK today. It is based on a review of the literature and also on a study performed at a grand rounds session at a district general hospital in the UK. The doctors who attended were asked to complete a purpose-designed questionnaire with open and closed questions based on an anonymous case history. Only after all the data sheets had been collected were the physicians told that the patient was Charles Darwin at the age of 56.

Darwin’s physicians

Extensive biographies have been written about many of the physicians Darwin consulted during his lifetime, including the eminent Professor Sir William Jenner and Dr. Henry Bence Jones. Professor Sir William Jenner of University College Hospital, London visited Darwin between March 20, 1864, and May 3, 1865. It seems that Professor Jenner’s working diagnosis was “gastritis,” for which he prescribed a long list of medications, especially antacids. Initially Darwin felt much better after Jenner’s visit. In August 1864, Jenner was able to reassure Darwin that there was no serious illness and a further consultation would not be of benefit.5 However, over the next year, the medications no longer relieved his symptoms and he asked for advice from his friend J.D. Hooker about consulting another physician.6

Henry Bence Jones was a prominent physician at St. George’s Hospital, London. He is best known today for describing the urinary protein in patients suffering from multiple myeloma. However, he had also published works on gout and was recognized as an authority on stomach and renal diseases. Darwin began to consult Bence Jones in July 1865, who treated him mainly with diet and exercise, together with various pills and potions. This again initially resulted in alleviation of his symptoms: “I am slowly getting better, & this I owe entirely I believe to Dr Bence Jones who has half-starved me to death & reduced my weight 15lb. but done me wonderful good.”7

Today’s physicians

Forty-six hospital doctors completed a questionnaire after hearing the symptoms and objective medical evidence recorded by Darwin in letters written up to the age of 56 (1865). They had varying levels of experience, from trainees to experienced consultants. The most common diagnoses were anxiety/panic attacks, vestibular disequilibrium, and chronic gastroenteritis. In this review, thirty-six doctors elected to refer the patient to another specialty.

Discussion

Today, there is detailed historical information available about Darwin’s life. His letters, especially those transcribed by the Darwin Correspondence Project, provide an insight into the natural progression of his illness and the response to a multitude of medications and holistic treatments. The nature of Charles Darwin’s chronic illness has provoked many opinions from individual physicians and historians. However, a study to record the views of a group of doctors currently in practice in the UK had not been attempted before.

A review of the literature revealed that fifty-four medical and non-medical authors have published forty-six diagnoses in sixty-five papers. The most common diagnoses come under the headings of psychoanalytical (9), psychiatric (5), and organic disease (32), with anxiety/neurosis and chronic gastroenteritis leading the list.

One senior physician in the grand rounds study confidently diagnosed Lyme disease from the symptoms presented. Otherwise, most physicians proposed three or four possibilities. Most of Darwin’s doctors also did not commit to a diagnosis, but their treatments suggest that they suspected gastritis. This was also reflected in the treatments suggested by seventeen of the doctors at the grand rounds session.

Physicians today are trained to focus on their own area of specialization and to refer a patient to colleagues when this is appropriate. This situation may not have been as common in the nineteenth century, but Darwin also sought advice from physicians who specialized in different areas. It is interesting to note that the treatments these physicians suggested were little different from the general management offered today, except in one respect. Doctors today appreciate the role of stress and the benefits of mental health treatments, but this was not an option available in Darwin’s day. Sixteen out of forty-six doctors suggested stress management counseling for a patient with Darwin’s symptoms, reflecting a better knowledge of the interaction between mental health and physical symptoms.

Modern medical diagnosis often depends on expensive investigations which likewise were not available to Darwin’s physicians. It is no surprise that the doctors in the study suggested many different investigations for a patient with non-specific symptoms. The intriguing question is whether any of these modern investigations would have found a cause and led to a cure for Darwin’s illness. There is no information to assess whether any consideration was given to the cost of the investigations that were suggested. Cohen and Mackowiak stated that the cost in Maryland, USA, of investigating a patient with Darwin’s symptoms would have been $11,220 USD in 2013. They also outlined the considerable cost of possible treatments and operations in a modern health service.8

The volume of hospital notes regarding a patient presenting with Darwin’s symptoms would also be considerable because of the number of referrals, investigations, and treatments. It is likely that in Darwin’s time both the doctors and patient were frustrated, much as they would be today. One can sense this in Darwin’s letter: “Dr Jenner is exhausted as to doing me any good.”9 There may be a temptation to be critical of medical colleagues from the nineteenth century and the authors who have proposed diagnoses since then. However, Charles Darwin was an intelligent, introspective scientist who explored every possible way of arriving at a diagnosis for his very troublesome symptoms. He must have been a challenging patient to manage. His symptoms eventually settled in 1866, and his letters thereafter refer more to the effects of aging until his final illness in 1882.

Conclusion

The doctors that Darwin consulted in 1863 to 1865 seem to have correctly excluded any serious disease, and were probably as near as any modern doctor to the correct diagnosis. This review suggests that even with so much evidence from his own letters, autobiography, and health diary, today’s hospital doctors are no nearer to agreeing on a diagnosis of Darwin’s chronic illness than the most eminent doctors of his day.

It is worth noting that, despite his chronic symptoms, Darwin lived to the age of seventy-three and died of angina and heart failure.10 His obituary in the BMJ reported that “during all his life he suffered from a condition of the nervous system reacting upon the digestive organs which necessitated the greatest care.”11 It is likely that doctors and non-medical authors will continue to be intrigued by this medical conundrum. Further research may lead to new insights, professional enjoyment, and lively debates about the cause of Darwin’s chronic illness.

End notes

- Adrian Desmond and James Moore, Darwin: The Life of a Tormented Evolutionist (London: Penguin Books, 1992), 27.

- Janet Browne, Charles Darwin: A Biography, Vol.2 – The Power of Place (London: Pimlico, 2003), 227-44.

- William Sheehan, William Meller, and Steven Thurber, “More on Darwin’s illness: comment on the final diagnosis of Charles Darwin,” The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science 62 (Feb 2008): 205-209.

- News Press, “DNA from beard solves 130-yr-old riddle of Darwin’s mystery illness,” https://www.channel4.com/press/news/dna-beard-solves-130-yr-old-riddle-darwins-mystery-illness.

- Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 4589,” https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-4589.xml.

- Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 4805,” https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-4805.xml.

- Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 4909,” https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-4909.xml.

- S. Cohen and PA Mackowiak, “Diagnosing Darwin,” The Pharos of Alpha Omega Alpha-Honor Medical Society Alpha Omega Alpha 76, no. 2 (2013): 12-17.

- Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 4742,” https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/?docId=letters/DCP-LETT-4742.xml.

- Ralph Colp, Darwin’s Illness (US: University Press of Florida, 2008), 116-20.

- “Charles Darwin,” BMJ (April 29, 1882).

STEPHEN KENT was born in Shrewsbury, UK, and has had a life-long interest in Charles Darwin. He has presented at the British Society for the History of ENT and published an article entitled “An Otolaryngologist’s Interest in Charles Darwin” in the Journal of Laryngology and Otology.

Leave a Reply