Scott Sikkema

Chicago, Illinois, United States

“Man’s ability to measure the spiritual, earthbound and cosmic, set against his physical helplessness; this is his fundamental tragedy. The tragedy of spirituality. The consequence of this simultaneous helplessness of the body and mobility of the spirit is the dichotomy of human existence.”

—Paul Klee (The Notebooks of Paul Klee)

In the hospital each week, there is an open conversation group for cell therapy transplant patients. Our adept facilitators pose such questions of a dichotomous nature as how do we feel lucky and unlucky in relation to what we have and are going through. Questions like these push me into areas of doubt, wonder, ambiguity, not knowing, all of which can be generative.

When my mother died in the spring of 2022, I needed something to aid me in centering myself. I went to the small town library that I had grown up with, and checked out a big survey book of Italian frescoes. There were magnificent examples throughout the book, but I found myself repeatedly drawn to Piero della Francesca’s cycle of frescoes depicting The Story of the True Cross at the Basilica of San Francesco at Arezzo, Italy, created in the mid-to-late 1400s. The figures in these frescoes have an ethereal, mysterious quality that have enthralled for centuries and eluded many artists and writers in the twentieth century as well as today. Their subtle faces and poses, connected but distinct and deliberative, give them a hieratic quality that simultaneously demands contemplation and evokes mystery. The figures and della Francesca’s use of color and geometric space create a sense of unknowing that is curiously centering—the realization of the strength that comes from knowing something, but at the same time knowing the larger power of not knowing. In a 1965 essay on Piero della Francesca, the American painter Phillip Guston wrote that della Francesca’s paintings have “a wisdom which can include the partial doubt of the final destiny of its forms. It may be this doubt that moves and transforms everything.”1

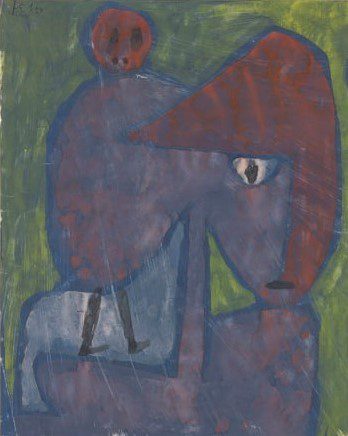

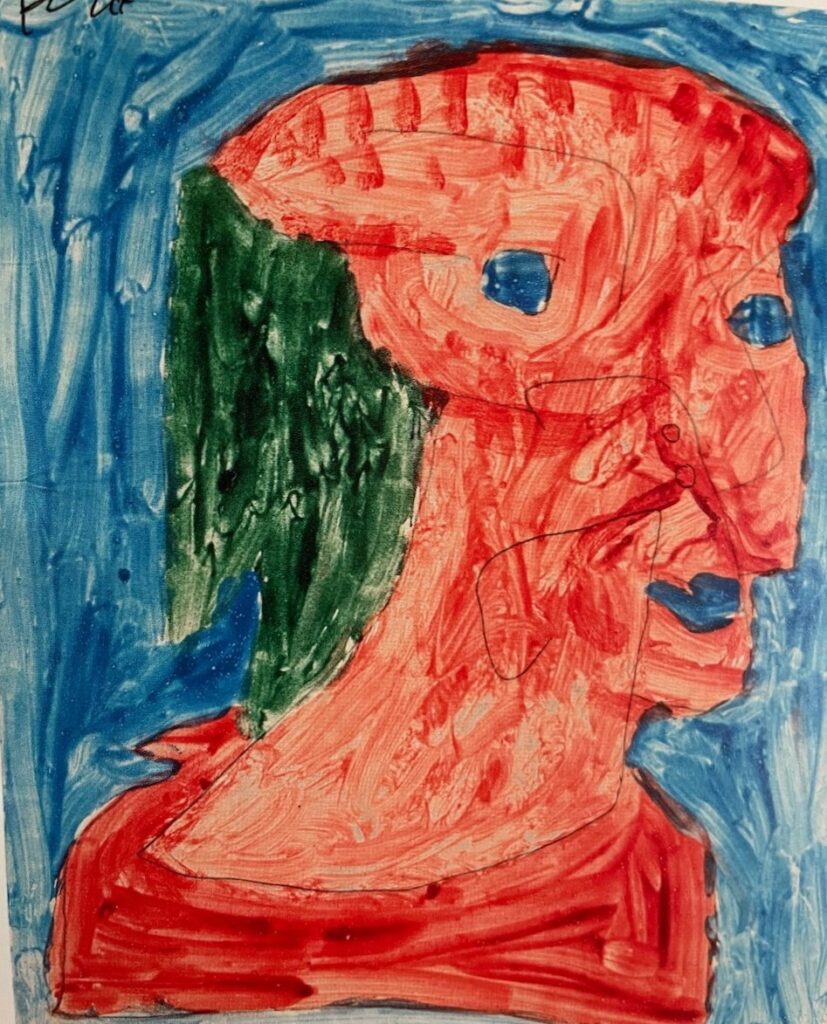

Last winter, while recuperating from a cancer operation at a friend’s home filled with art books, I was struck by an extraordinarily beautiful coffee table book, printed on onionskin paper, of the frescoes at Arezzo. I was once again drawn to and centered by these images, and I have been looking at them ever since. In the spring of 2023, I came upon another set of images that compel me. David Zwirner Gallery published the catalogue Paul Klee: 1939 to accompany their exhibition of the same name. The works were all from the last calendar year of Paul Klee’s life (he died in late June 1940). By 1939, Klee had for years suffered from a rare autoimmune disease, which was not fully diagnosed in his lifetime. His diagnosis still remains of some conjecture, since his medical records are long gone. Despite his illness, Klee managed to create more than 1,200 works in 1939 alone, and the exhibition and catalogue were culled from a fraction of this work. Looking through these images, I find them, like Klee in general, simultaneously engaging and inviting yet denying easy access of meaning. A brilliant notion of the exhibition organizers was to bring in the contemporary artist Richard Tuttle to write poetry in response to Klee. In one of Tuttle’s poems, he writes that Klee’s art “operates like an aura in front of the work”, which you enter first, before the work. And yet, you don’t fully. Tuttle writes,

You don’t

enter the aura You

stay out

side like

touching

a bubble

Thus at

The same

time you

enter the

work you

are outside

the bub

ble2

As I viewed Klee’s work in this catalogue, I felt a similar sensation to my experiences of della Francesca—the realization of the strength of knowing something but knowing the larger power of not knowing. I found myself struck by what I saw as a comparable hieratic quality in some of Klee’s visages with those of della Francesca. I was “touching the bubble,” entering the work, yet also outside the bubble.

Lucky or unlucky, fair or unfair—such dichotomies don’t offer quick or set answers with cancer. In an interview with Bomb Magazine, Richard Tuttle states that the job of artists is to “span polarities that cannot be spanned in the world,” and art’s power of spanning helps me as I see works by della Francesca and Klee.3 I will continue to see their work, and work by other artists, as I move forward in my journey. It is a journey with so little settled it seems to me, and I need to draw upon something that is immutable, but at the same time offers no definitive or singular answer. Phillip Guston in his 1965 essay on della Francesca wrote, “Possibly it is not a ‘picture’ we see, but the presence of a necessary and generous law.”4 The last image in Paul Klee: 1939 is a drawing by Klee that he titled “Just Can’t Get It,” with a fragmented bust of a figure whose expression and gesture indicate puzzlement. For Klee this is not a negative puzzlement, but a generative and centering puzzlement in contemplation of this spanning of polarities, the “necessary and generous law,” and that realization of the strength of knowing something but knowing, once again, the larger power of not knowing.

References

- Guston, Phillip. “Piero della Francesca: The impossibility of painting.” ARTnews, From the Archives, May 12, 2017. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/retrospective/from-the-archives-philip-guston-on-piero-della-francesca-in-1965-8320/.

- Tuttle, Richard, “Psyche,” in Paul Klee: 1939 (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2021), 24.

- Yerebakan, Osman Can. “Dissimilarity in Unity: Richard Tuttle Interviewed by Osman Can Yerebakan.” Bomb Magazine, December 9, 2019. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/dissimilarity-in-unity-richard-tuttle-interviewed/

- Guston, “Piero della Francesca: The Impossibility of painting.”

SCOTT SIKKEMA has worked in leadership roles in arts education and education for over 30 years. He has focused on research as an aesthetic and pedagogical practice, exploring via inquiry site, space, time, process, and other queries. He has led many collaborations, written numerous grants, and has published a variety of articles.

Leave a Reply