Giulio Nicita

Florence, Italy

1983

Giuseppe’s shouts and laughter echoed in the long corridor as he ran after the ball, kicking it toward his mother with his slippered foot. Attracted by the noise, but silently sliding along the polished floor, the austere figure of Sister Leonia appeared, her face surrounded by her veil. With a smile on her lips to mitigate the authoritative order, she said, “Silence please, it’s time to sleep!”

Giuseppe’s mother picked up the ball, took her pajamaed son by the hand, and went back into his room. She made him brush his teeth and wash his face, and then she put him to bed.

Giuseppe sank into a child’s deep sleep, unaware of his mother’s thoughts that would torment her during the long night in the urology department. She reminisced about the longed-for child, the joy when he arrived, and the subsequent worries about the fevers that slowed his growth. Those anxieties dragged on for some time before the cause was identified: a rare malformation of the urinary tract, a bilateral mega-ureter. There had been surgeries to correct the defects, which had wracked the abdomen of the small child. Now, at the age of eight, Giuseppe was skinny and below average in height. He had spent a lot of time in the hospital which was now almost a second home, and the doctors and nurses had grown fond of the child. Despite suffering from the disease and its treatment, he was full of vitality. As soon as he began to feel better, he would chase a ball through the corridors and the dormitories of the department. But his mother knew from the doctors that the malformations had irreversibly damaged his kidneys despite the surgical interventions, and treatment by dialysis would begin for him within a few months. She began to cry silently and fell asleep only when there were no tears left.

1985

The elderly professor’s droopy eyes and the drops of sweat on his forehead betrayed his physical fatigue, but his joyful tone and cheerful gaze communicated his satisfaction about the surgeries: “Dear Mario, my fingers are crossed. Both interventions were without problems. Your wife’s nephrectomy is complete. She’s already awake and in fine condition in the recovery ward. We’ll send her back to her room in a couple of hours. Giuseppe’s transplant, too, went smoothly. Your wife’s kidney, itself perfect for your son, has already started producing urine. His mother has given him life again.” Mario squeezed the professor’s hand between his and meant to kiss it, but the doctor drew it back, saying, “Mario, let’s not joke, I’m not the Pope. Tomorrow morning you will be able to see your son.” The tension that had gripped Mario for two days with fear of the risks to his wife and son dissolved. Tiredness washed over him suddenly, but his head felt light. He wanted to see his wife and then rest; the professor’s words had reassured him. He telephoned the good news to his boss, the police commissioner, who was eager to know about the operations. Mario’s colleagues also knew of the family’s misfortune and had followed Giuseppe’s year of dialysis—three treatments per week—and knew the boy was to receive a kidney from his mother. Whenever Mario had needed a substitute for his shifts, his colleagues had always stepped up.

Mario gladly would have donated one of his kidneys to Giuseppe, because he loved his son but also to compensate his wife for her years of absolute dedication. But to his dissatisfaction, his organs were less compatible than his wife’s. Since compatibility is the best guarantee of transplant success over time, it had been decided to harvest the maternal organ. The last two months had flown by with appointments, analyses, interviews, documents to complete, and finally, that morning, the simultaneous operations. The mother’s nephrectomy took place in one operating room, and Giuseppe’s began in another as soon as the organ arrived there. If the surgeries had gone well, as the professor claimed, the family’s bad luck would have finally passed. A less problematic existence could begin for all of them.

2008

On a late spring morning, another surgeon sat with his feet propped on his desk to relieve his legs. Satisfied with the surgery just completed on the patient he had known since his lively childhood, he thought of Giuseppe’s still great enthusiasm for the local soccer team, la Fiorentina. The doctor thought too of the time that had passed since he was a young assistant of the professor who had transplanted the kidney from the mother into the boy. For twenty years the organ had functioned well, but then a progressive decline had begun. A year and a half earlier, Giuseppe once again began dialysis. He disliked the dialysis treatments just as intensely as he had as a boy and had insistently asked for another transplant.

This time the kidney was to come from a cadaver donor. Giuseppe’s mother had only one kidney left, and his father had died three years earlier from a stroke. Fortunately, Giuseppe had priority on the waiting list because he had a previous transplant and was not “hyperimmune.” In other words, he had no excess antibodies in his blood, a condition that prevents those affected from finding a compatible organ. His wait time for the surgery was just over a year, well under the average. The non-functioning kidney—the first transplant—was in the right iliac fossa, and it was not necessary to remove it. The new organ was taken from a young donor who had been the victim of an accident at work. After some weeks in intensive care he had finally died, but his kidney appeared healthy, was large in size, and was well preserved in preoperative hypothermia. The surgeon had anastomosed it to Giuseppe’s left iliac vessels. Suturing the vascular structures had been easy, and at the end of the operation the organ had regained a rosy, uniform color. Most important, it had immediately produced urine, a highly favorable prognostic sign. The doctor had high hopes for a normal post-operative period. In fact, after ten days, Giuseppe was discharged home.

Three weeks later, the surgeon was called in haste for an emergency. A girl with a recent kidney transplant had symptoms of massive bleeding during a routine hospital follow-up. She was immediately taken to the operating room where the surgeon removed the kidney. The renal and iliac arteries were eroded, almost crushed, and the operation was difficult. Had the problem arisen anywhere outside the hospital, it would have been very hard to save her.

The girls’ arteries had been colonized by a fungal infection from the donor kidney, which had been asymptomatic during the time in intensive care. The pathogens were later transmitted to the recipient via the transplant and had progressively worsened.1,2 With dismay, the doctor realized that in all likelihood the other kidney from this donor was similarly infected: Giuseppe’s kidney was in question!

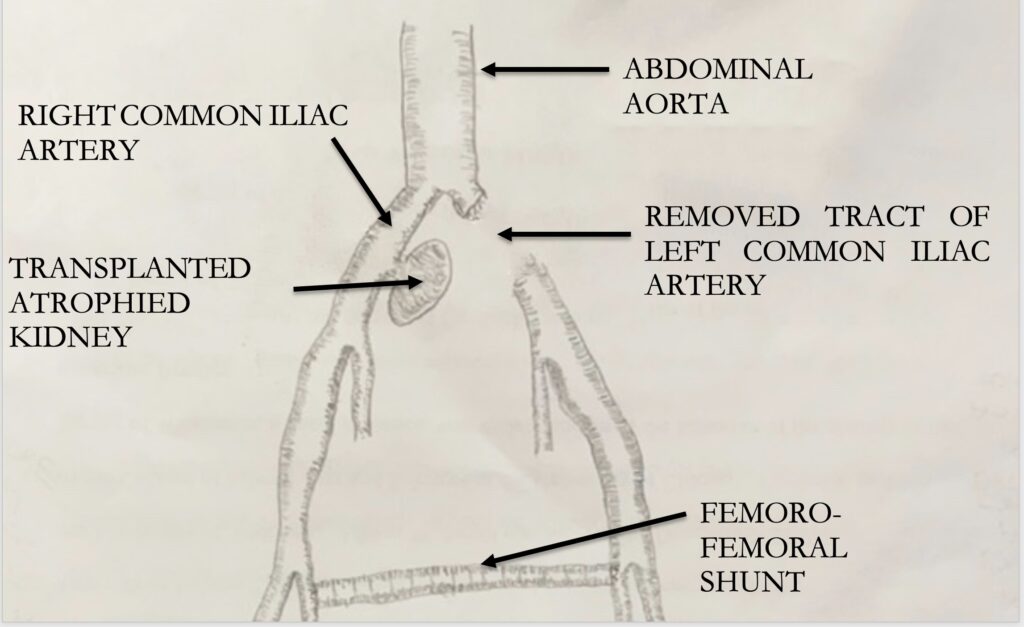

Giuseppe was summoned immediately. Fortunately, an angiographic examination proved that his arteries were still in the pre-rupture stage. The surgeon, much aggrieved, explained that he would have to remove the new kidney. Giuseppe became desperate and fought the medical advice. Only reluctantly and after a long and heartfelt discussion did he agree to the operation. The recently transplanted organ was removed along with a section of the infected iliac artery. Because of the great probability of contamination, it was impossible to insert a prosthesis directly between the two stumps of the removed artery. Instead, to maintain the arterial blood supply to the left lower limb, a shunt was constructed between the right and left femoral arteries, and the prosthesis was made to pass across an infection-free path (Fig. 1). One bad turn had followed another for Giuseppe. As we say, when it rains, it pours. As Giuseppe returned to dialysis for the third time, to the great sadness of the surgeon as well as his patient, the prospect of a new transplant was even more remote.

And we come to the end of the story. Bad luck in health had followed Giuseppe from the beginning, with worse than good times. Did bad luck also haunt the surgeon? After Giuseppe’s last operation, the doctor reflected on medicine’s eternal dilemma: respect current practice or venture into unknown territory? Transplanting an organ from a donor long in intensive care opens the recipient to the risk of latent infection, as happened to Giuseppe. At the same time, one unwillingly discards a kidney apparently in good condition because of the scarcity of organs. Daily a surgeon makes choices, mostly correct but sometimes wrong. The point is to refrain from exaltation at success and to guard against depression in cases like Giuseppe’s, when the rain pours.

References

- Lazareth H et al, “Renal Arterial Mycotic Aneurism after Kidney transplantation,” Urology Aug 2017;106:e7-e8.

- Lacombe M, “Mycotic aneurism after kidney transplantation,” Chirurgie Dec 1999;124(6):649-54.

GIULIO NICITA, MD, held the Chair of Full Professor of Urology at the University of Florence from 2002 until 2016 after a career begun there as resident in 1972. His fields of clinical study were urological oncology, female urology, and kidney transplantation. He is the author of numerous articles published in Italian and international journals.

Leave a Reply