Sally Metzler

Chicago, Illinois, United States

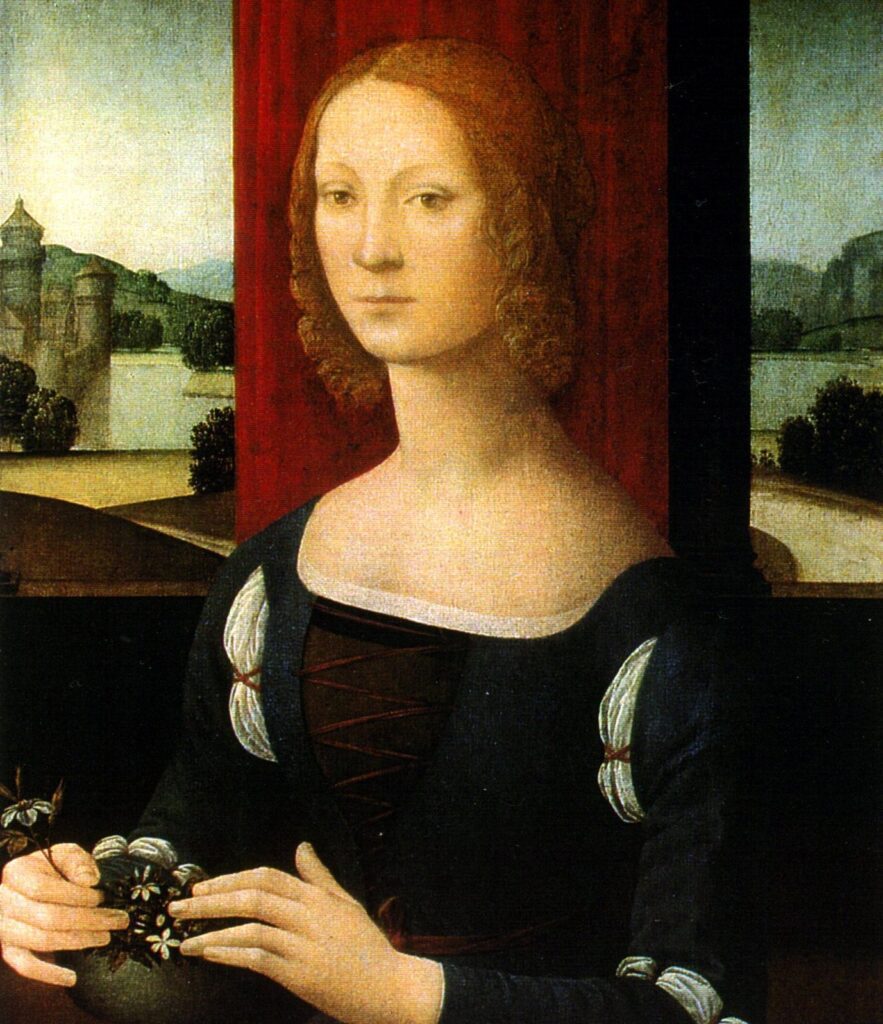

Fearless, beautiful, and cunning, Caterina Sforza (1462–1509) fought heroically to defend her fiefdoms of Imola and Forli until the bitter end. Even the celebrated and infamous Renaissance strategist, Niccolò Machiavelli, remarked that he had met his match in Caterina, and confessed he could not outwit her. Historians laud her as a “wonder of her age, a woman of almost superhuman ability.”1

Though her last and most loving marriage was to a Medici, paradoxically her first betrothal was to one of the Medici’s most vociferous and vehement enemies, Giralomo Riario. A nephew of Pope Sixtus IV, spiteful and despised by many, Riario participated in the plot to assassinate Medici Lorenzo the Magnificent and his younger brother Guiliano. Caterina was the daughter of Galeazzo Sforza, the eldest son of famed condottiere Francesco Sforza, a mercenary soldier who rose to become the Duke of Milan. His skills and bravery earned him the sobriquet Sforza, meaning “strong,” and throughout her life Caterina validated this inherited trait of character. In 1488, after the assassination of her husband Riario, Caterina became Regent of Imola and Forli. She remarried one year later, this time to a soldier named Giacomo Feo. Assuming the role of husband to Caterina Sforza proved a dangerous endeavor. In 1495, as with her first husband Riario, Feo was also assassinated. The conspirators, jealous of Feo’s advancement in society, stabbed him as he returned with his family from a hunting party. Caterina witnessed the tragedy and pledged scathing revenge.

Concerning her resolute courage and steadfastness, as Ceasare Borgia’s troops threatened the very existence of Imola during the 1499 siege, Caterina informed him that “she was the daughter of one who knew no fear and was determined to walk in his steps till death.”2 When she was not saving her kingdom or thwarting invaders and conspirators, Caterina directed her energies towards studying alchemy, medicine, and cosmetics. She gathered her research in a manuscript titled Gli Experimenti de la Ex.ma S.r Caterina da Furlj Matre de lo inllux.mo S.r Giouanni de Medici, or simply known as Gli Experimenti—The Experiments.

Gli Experimenti offered remedies for myriad afflictions ranging from fever and headache to the more improbable of relieving epilepsy, curing infertility, enhancing libido, and even restoring virginity. In many respects, her potions represented the drugstores and beauty supply stores of today. Renaissance men and women explored home remedies for a variety of medical and self-improvement needs. And it was not uncommon to cultivate herbal and medicinal gardens, as did Caterina Sforza, thus availing herself at any time of the necessary ingredients. On the grounds of her Forli fortress of Ravaldino, she had a laboratory at her disposal for her studies.3

Though Caterina’s original manuscript is lost, Lucantonio Cuppano (1507–1560), a colonel who served under Caterina’s son (the revered soldier of fortune Giovanni delle Bade Nere), fortunately transcribed many of her experiments and formulas. Gli Experimenti was later translated and published by Pier Pasolini in the late nineteenth century. Over 550 recipes appear in Gli Experimenti, divided into three main categories: medicine, “lisci” (cosmetics) and “chimica” (chemistry). Among the more imaginative prescriptions, in the medicinal division we find that “for infirm lungs, an ointment is to be made of the blood of a hen, a duck, a pig, a goose, mixed with fresh butter and white wax” and applied to the chest with a fox’s skin.4

Crossing into the boundaries of beauty and medicine, Caterina offers a prescription to grow hair:

Water to make the hair grow beautiful and long to the ground: Take the same amount of three-leaved marshmallows, parsley roots and parsley leaves. Boil the ingredients in a new pot with water and vinegar. After some time, strain the liquid through a felt cloth and squeeze well. Wet your head often with this water and you will see amazing and extraordinary results.5

She recommends drinking a concoction of the plant salvo or corniola (broom), found when mowing wheat, and mixing with wine to assist one in urinating a kidney stone. The process could take as long as five months, she warns.6

Against hardness of hearing, Caterina recommended:

Take the juice of wild cucumber leaves (the variety of cucumber that grows spontaneously). Place it on the ear and it will get rid of the pain and restore the hearing.

Here is another method: take earthworms, ant eggs and rue stalks. Mince them together and boil them in rose oil. Strain and place one drop of lukewarm liquid in the ear, then insert some cotton wool to plug it. Apply some oil outside and around the ear and the hearing will come back.7

Among the many vicissitudes of her life, Caterina thrice endured widowhood, losing her beloved Giovanni di Medici (Giovanni Popolano) in 1498 only months after the birth of their son, the future Giovanni delle Bande Nere and father of Cosimo I Grand Duke of Tuscany. A few years later, in January of 1500 following her defeat at Forli, Ceasare Borgia commanded her to Rome and imprisoned her in the dungeons of the Castel San Angelo. She languished for months and nearly starved to death, her beauty barely recognizable. Released in July of 1501, Caterina fled to Florence to be reunited with her family and received a warm welcome from the Florentines. But these initial halcyon days of her final sojourn in Tuscany dissipated, and once again Caterina confronted obstacles. Family members made attempts to dispossess her of both the young Giovanni and her late husband’s Villa da Castello. At the age of forty-seven, in May 1509, Caterina succumbed to pneumonia and died. For all her sufferings, she remained silent and stalwart, only uttering to her Dominican confessor: “Could I write all, the world would turn to stone.”8

References

- GF Young, The Medici (NY: Random House, 1901), 509, 525.

- Young, 529.

- Anna Palmieri, Caterina Sforza and Experimenti. Translation into English and historical-linguistic analysis of some of her recipes (Università di Bologna, 2016/2017), 6.

- Paul Engle, “The Life and Times of 17th Century Glassmaker Antonio Neri,” Conciatore, March 8, 2017, https://www.conciatore.org/2017/03/caterina-sforza.html.

- Palmieri, 20.

- Palmieri, 23.

- Palmieri, 24.

- Young, 531. For further reading on the life and influence of Caterina Sforza, see: Joyce DeVries, Caterina Sforza and the Art of Appearances: Gender, Art and Culture in Early Modern Italy (Women and Gender in the Early Modern World) (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2010) and Elizabeth Lev, The Tigress of Forli: Renaissance Italy’s Most Courageous and Notorious Countess, Caterina Riario Sforza de’ Medici, 2012.

DR. SALLY METZLER is an art historian and currently the chair of the Hektoen Covid-19 Monument of Honor, Remembrance, and Resilience.

Leave a Reply