JMS Pearce

Hull, England

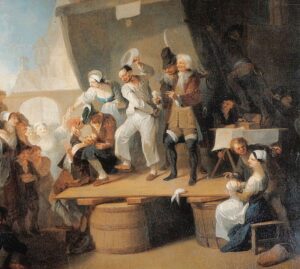

Today, the conjunction of two such opposite functions as haircutting and surgery seems incongruous. Amongst early monasteries in England were St. Augustine’s in Canterbury, founded in AD 598 by St. Augustine, and Lindisfarne Priory on Holy Island in Northumbria, founded by St. Aidan in AD 635. The monks employed barbers to have the defining bald spot on their heads suitably tonsured. Barbers would also perform bloodletting, pull teeth, or make ointments. Dating from ancient civilizations of Egypt, Greece, and Rome,1 the barber-surgeons became common in medieval Europe, along with other folk healers, apothecaries, herbalists, and “quacks” who attended the sick.

In the Middle Ages, surgery was deemed a lowly, semi-skilled occupation. Widespread poverty, squalid housing, contaminated drinking water, and excrement did not improve the prospects of surgery. Since results were generally poor, physicians avoided surgery. Physicians were considered highly educated, wrote in Latin, and considered the practice of surgery beneath their dignity. This gave the opportunity for barber-surgeons to work and prosper.

hat were the operations commonly performed? Phlebotomy, herniorrhaphy, lithotomy, draining abscesses, and treating fractures by applying plasters were the most frequent. The well-known red-and-white striped pole found outside barbers’ shops indicated the blood and towels used in bloodletting. More proficient practitioners would open the abdomen for removal of a diseased organ, but at high risk. Cutting for bladder stone (lithotomy) was feared for its high mortality rate and frequent complications of hemorrhage and infection.

One famous survivor was the famous diarist Samuel Pepys. In Pepys’s cousin Mrs. Turner’s house, Thomas Hollier, a St. Thomas’s Hospital surgeon, cut Samuel Pepys for the stone through the perineum without anesthetic. (On the anniversary, Pepys hosted a dinner for his friends and his surgeon to celebrate his survival.) Another high-risk operation undertaken by a skilled surgeon was limb amputation, usually performed for major trauma or gangrene, and again, often attended by complications of sepsis and blood loss.

Physicians were an educated hegemony of the medical world, mostly treating the rich and the aristocracy, but avoiding surgery. Led by the scholar Thomas Linacre, the College of Physicians was founded in 1518 by Royal Charter from King Henry VIII. A degree gave a license to practice but also to punish unqualified practitioners and quacks. Only with the restoration of the monarchy in the late 1600s did the RCP consistently refer to itself as “royal.”

Much earlier, The Worshipful Company of Barbers was recognized in 1308. Barber-surgeons often became Freemen of their local town. Many such companies were joined with the Wax and Tallow Chandlers such as those in Chester, Newcastle, and Norwich.

Alongside the Barbers’ Company in 1435, a London Guild (Guild of St. Magdalene) or Fellowship of Surgeons was created.

The better guilds provided strict training and examinations of competence and had defined codes of practice. John McNee, professor of medicine in Glasgow and past master of the Company of Barber-Surgeons of London, gave an elegant lecture on the subject.2

Disputes between surgeons and barber-surgeons were a vexing, recurring problem.3 In 1540, the union of the Worshipful Company of Barbers (incorporated 1462) and the Guild of Surgeons was initiated by Thomas Vicary, surgeon to Henry VIII, to form the Company of Barber-Surgeons.4 The act decreed that no surgeon was to perform the tasks of a barber and vice versa, but both could draw teeth. Vicary is still commemorated by the Thomas Vicary Lecture delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

Surgery became more rational when in 1543 Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564), who worked in Padua, published his monumental De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem. It provided surgeons with the first detailed and accurate account of human anatomy on which to base their operations.

Ambroise Paré (1510–1590) was the most famous of the barber-surgeons.5 He greatly advanced the surgery of war injuries and devised techniques to aid wound healing, bloodletting, blood vessel ligation, and Caesarean section. He was admitted to the College of Surgeons in 1554 and is sometimes described as the “Father of Modern Surgery.” The barber-surgeon John Ranby, an anatomist and surgeon, along with William Cheselden was largely instrumental in the separation of the surgeons from the barbers. Another who broke with the barber-surgeons was Percival Pott, who operated at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, remembered for Pott’s disease of the spine and Pott’s ankle fracture.

The barber-surgeons were together for 205 years. Continuing professional disputes and jealousies led in 1745 to the Guild of Surgeons’ split from the Barbers’ Company to form the Company of Surgeons, whose hall was on the east side of the Old Bailey, next to Newgate Prison. This marked the end of the barber-surgeons. In 1800, a Royal Charter elevated the Guild of Surgeons to the Royal College of Surgeons (RCS), which became the English College in 1843 and is now sited at Lincoln’s Inn Fields.6 The Fellowship of Surgeons was a trade whose members were trained by apprenticeship rather than by universities and were therefore called Mr., not Dr.—a tradition that persists. The barber-surgeons of Edinburgh in 1505 were similarly incorporated as a craft guild, but not until 1778 did a royal charter grant their recognition as The Royal College of Surgeons of the City of Edinburgh (RCSEd). A similar college existed in Ireland (RCSI). The acquisition of one of these diplomas was required to practice as a surgeon in Britain.

The barber-surgeons Percival Pott and William Cheselden taught John Hunter FRS (1728–1793), distinguished surgeon and founder of The London Royal College’s Hunterian Museum. He was an influential teacher of the scientific method, who learned his anatomy at the Great Windmill Street library, museum, and anatomy theater founded by his equally distinguished elder brother William, an anatomist and obstetrician.

How they obtained cadavers for anatomical study is another well-known story.

References

- Pillay A. The barber-surgeons: Their history over the centuries. Hektoen International, Winter 2020.

- McNee J. Barber-surgeons in Great Britain and Ireland. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1959 Jan;24(1):1-20.

- Parker, G. Medical organisation and the growth of the medical sciences in the seventeenth century. Bristol med.chir.J. 1911;29: 201. Cited by McNee.1

- Wall, C. The History of the Surgeons Company, 1745-1800. The Thomas Vicary Lecture for1935. London: Hutchinson, 1937.

- Wilson M. Ambroise Pare: standard bearer for barber-surgery reform. Hektoen International, Winter 2020.

- History of the RCS. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/about-the-rcs/history-of-the-rcs/.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.

Leave a Reply