JMS Pearce

Hull, England

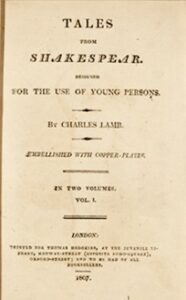

Many children and young people struggle with the plays of Shakespeare, whose language, poetic meters, and historical content are often baffling at first sight. Those who persevere and overcome these difficulties learn to love and wonder at Shakespeare’s unsurpassed language and humane tales of comedy, tragedy, and history. Many educational books and notes have been written to facilitate this passage of learning, but none can match the deserved cynosure: Lamb’s Tales from Shakespear,* which has never been out of print. It is often attributed to Charles Lamb, but the story behind The Tales is more intriguing.

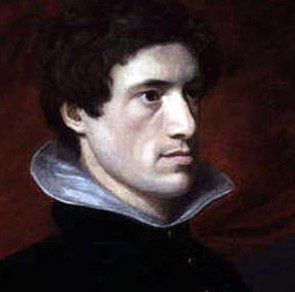

Charles Lamb (1775–1834) was the third surviving child of the seven children of John Lamb, a Hall waiter and clerk, serving Samuel Salt, a sub-treasurer of the Inner Temple, and John’s wife Elizabeth. The Lambs were housed in the back chamber of 2 Crown Office Row, behind Salt’s office. Charles was to become a highly regarded poet and essayist whose imaginative, humorous essays in the London Magazine were collected as Essays of Elia (1823) and The Last Essays of Elia (1833).

His older sister Mary Anne Lamb (1764–1847) was the second of the three children. Her brothers John and Charles were both educated at Christ’s Hospital whereas Mary had little schooling and was apprenticed to a needlewoman as a dressmaker to boost the family’s meager income.

From early childhood Mary’s relation with her mother, the victim of arthritis, was strained and emotionally distant. Despite her paltry education, Mary was an avid reader, having access to the library of her father’s employer, Samuel Salt. She taught herself Latin, French, and Italian. When Salt died in 1792, the family was obliged to leave his home at the Inner Temple and moved to humble lodgings at 7 Little Queen Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

A dramatic and unexpected tragedy occurred on 22 September 1796. Driven to distraction by her apprentice seamstress, Mary chased the girl round the room, and when her mother intervened, she fatally stabbed her mother with a knife through the heart. Charles Lamb described the events in a letter to his friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge:

I will only give you the outlines. My poor dear dearest sister in a fit of insanity has been the death of her own mother. I was at hand with only time enough to snatch the knife out of her grasp. She is at present in a madhouse, from whence I fear she must be moved to a hospital. God has preserved to me my senses…

At her trial the jury brought in in a verdict of lunacy and she was briefly removed to an asylum. She regained her sanity and was allowed to return home only on condition that a family member undertook her supervision and care. Fortunately, this was provided by her younger brother Charles who worked for the East India Company as a humble clerk and saved her from lifelong confinement in Bedlam (Bethlem Hospital).1 In this vital decision Charles devoted his life to Mary, a selfless sacrifice he maintained till his death, and remarkable since she had killed their mother.

Charles Lamb accepted more than his fraternal duty.2 He was considered to be exceptionally kind, free from affectation, and blessed with an innate sweetness and sparkling wit.3 It seems that he too had a nervous stammer and had suffered a solitary attack of delusional violence at Christmas 1795.

Mary’s extraordinary behavior was attributed to a sudden fit of insanity, caused by the strain of nursing a senile father and a disabled churlish mother, while working long hours at her needlework and dressmaking. Biographers have diagnosed Mary as suffering from manic-depressive (bipolar) illness. Neither Mary nor Charles married; they lived together with mutual devotion, though Mary continued with bouts of psychosis necessitating a straitjacket and her voluntary admissions to a “madhouse” on at least twenty occasions.3 Between such episodes she was intelligent, warm, supportive of Charles, and much admired by such friends as the writers ST Coleridge, William and Dorothy Wordsworth, Robert Southey, and William Hazlitt.4

In view of today’s strict regulations for adoption, it is interesting that in 1823 they were allowed to adopt Emma Isola, an orphan who ten years later married Charles Lamb’s publisher, Edward Moxon.

The full story of Mary’s insanity was not fully disclosed until Thomas Noon Talfourd’s account fifty years later.5 He described Mary’s affectionate relations with her brother:

There was no trace of insanity discernible in her manner to the most observant eye. In all its essential sweetness, her character was like her brother’s, while by a temper more placid, a spirit of enjoyment more serene she was enabled to guide, to counsel, to cheer him; and to protect him on the verge of the mysterious calamity from the depths of which she rose so often unruffled to his side. To a friend in any difficulty, she was the most comfortable of advisers the wisest of consolers. Hazlitt used to say that he never met with but one woman who could reason, and had met with only one thoroughly reasonable, the sole exception being Mary Lamb.

Tales from Shakespeare

Nine years after the murder, Mary Jane Godwin, wife of William Godwin, a publisher of children’s books, in 1805/6 asked Mary and Charles to write a shortened account of Shakespeare’s plays. It aimed to bring Shakespeare’s plays to life for children. Accordingly, in 1807 Tales from Shakspeare, Designed for the Use of Young Persons was published. The preface reads:

THE following Tales are meant to be submitted to the young reader as an introduction to the study of Shakespeare, for which purpose his words are used whenever it seemed possible to bring them in; and in whatever has been added to give them the regular form of a connected story, diligent are has been taken to select such words as might least interrupt the effect of the beautiful English tongue in which he wrote: therefore, words introduced into our language since his time have been as far as possible avoided.

But it was published under the name of Charles Lamb who had written only the sections of Shakespeare’s tragedies. This may reflect Mary’s wish to avoid any publicity because of her illness. But gender prejudices against women writers were also deeply entrenched at that time—witness the aliases of the Bronte sisters, George Eliot, and many others. Mary’s name finally appeared on the title page in the seventh edition in 1838. Lamb’s Tales retained as much authentic Shakespearean language as was fitting for children’s understanding. It condensed accurately twenty of the original thirty-eight plays, the comedies and tragedies, but omitted the histories. Working together (a “double singleness” as Charles called it),6 Mary wrote fourteen of the twenty plays.

| Tales from Shakespear, Contents |

| 1. The Tempest (Mary Lamb) |

| 2. A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Mary Lamb) |

| 3. The Winter’s Tale (Mary Lamb) |

| 4. Much Ado About Nothing (Mary Lamb) |

| 5. As You Like It (Mary Lamb) |

| 6. Two Gentlemen of Verona (Mary Lamb) |

| 7. The Merchant of Venice (Mary Lamb) |

| 8. Cymbeline (Mary Lamb) |

| 9. King Lear (Charles Lamb) |

| 10. Macbeth (Charles Lamb) |

| 11. All’s Well That Ends Well (Mary Lamb) |

| 12. The Taming of the Shrew (Mary Lamb) |

| 13. The Comedy of Errors (Mary Lamb) |

| 14. Measure for Measure (Mary Lamb) |

| 15. Twelfth Night (Mary Lamb) |

| 16. Timon of Athens (Charles Lamb) |

| 17. Romeo and Juliet (Charles Lamb) |

| 18. Hamlet, Prince of Denmark (Charles Lamb) |

| 19. Othello (Charles Lamb) |

| 20. Pericles, Prince of Tyre (Mary Lamb) |

Translated into forty languages, it became one of the most loved of children’s books, comparable to Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows, and JK Rowling’s Harry Potter series. Over two hundred separate English editions have been produced since 1807.

Charles and Mary published together two further books for Mrs. Godwin’s Juvenile Library: collections of Poetry for Children (1809), and Mrs. Leicester’s School, or, The History of Several Young Ladies, Related by themselves, in which they drew children’s attention to the lack of jobs for women, their poor pay, and the hazards of undue parental pressure. Both show Mary’s skill in creating engaging and fashionably moralistic stories and her attempt to warn readers of the domestic stresses she had endured.

Her writing was lucid and well suited to her young readers. They were published anonymously or under Charles’s name in order to shield Mary from unwanted publicity. Not confined to children’s books, she published other essays including (under the pseudonym Sempronia) On Needle-work published in 1815.

It is unusual that Mary retained the ability to write and edit so skillfully and clearly without evident distortion of reality, despite the burden of frequent episodes of delusional psychosis. These attacks of psychosis increased in severity and length during the 1820s. Owing to her notoriety, they were forced to move home on several occasions. Although their mutual devotion was unsullied, her illness took its toll on Charles’s health, causing depression and alcoholism. He frequented the “Charles Lamb pub” in Elias Street, Islington.

Detailed accounts of the life, letters, and family of Mary Lamb are those of Marrs7 and Kathy Watson.8 The Charles Lamb Society was founded in 1935, marking the centenary of his death.

Charles died of erysipelas in 1834. Mary Lamb outlived him by thirteen years, only intermittently in her right mind. By 1842 she had moved into a house with a private nurse. She died on 20 May 1847, and was buried with Charles (Fig 3) in Edmonton churchyard, Middlesex.

Note

The spelling of “Shakespeare” varied frequently in his lifetime. E.g., it is “Shakspeare” in the fifth edition.

References

- Lucas E V, editor. The works of Charles and Mary Lamb, 7 vols. 1903-5.

- McCrum R. The 100 best nonfiction books: No 73 – Tales from Shakespeare by Charles and Mary Lamb (1807). The Guardian, June 26, 2017.

- Pitfield RL. A Pitiful, Ricketty, Gasping, Staggering, Stuttering Tomfool: The Mental Afflictions of Charles and Mary Lamb. Ann Med Hist. 1929;1(4):383-93.

- Balle MB. Mary Lamb: Her Mental Health Issues. Journal of the Charles Lamb Society 1996;(93):2-12.

- Talfourd TN. Final Memorials of Charles Lamb. 1848.

- Aaron JA Double Singleness: Gender and the Writings of Charles and Mary Lamb. Clarendon, Oxford, 1991.

- Marrs EW, editor. The letters of Charles and Mary Anne Lamb. Cornell University Press, 1975. [Contains 1,200 of their letters]

- Watson K. The Devil Kissed Her. Bloomsbury, 2004.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.

Leave a Reply