Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

“Famine was part of everyday life.”1

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525–1569), one of the most accomplished Netherlandish painters, often used peasant life as his subject. The survival of peasant agricultural society depended entirely on the success of their crops. The dream of abundant food, available without working for it, was the theme of Bruegel’s The Land of Cockaigne (1567). In this painting, roofs are tiled with pies; “lazy and gluttonous farmers, soldiers, and clerks get and taste all without working. The gardens are sausages…the fowl fly by already roasted.”2 This is the fantasy of people living in a land of “ever recurring famine.”3

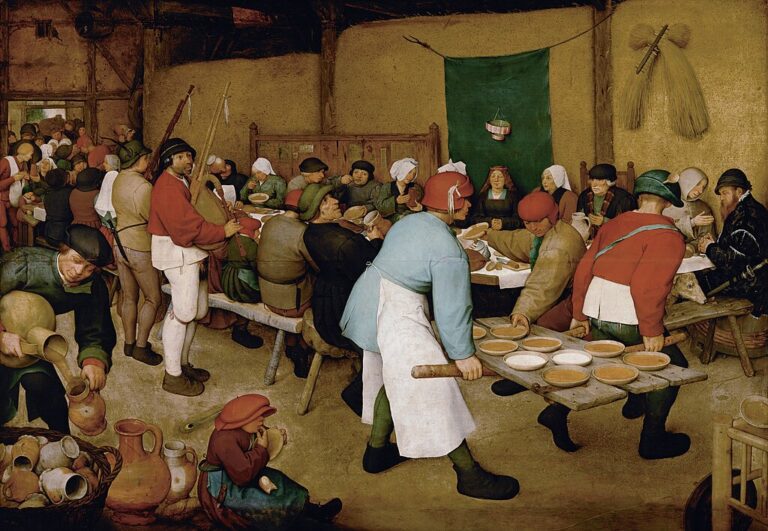

Food of lesser cost and variety but also in abundance is seen in The Peasant Wedding Banquet (1568). In it, a door taken off its hinges is used to transport bowls of food to the seated guests. Experts have said that these bowls hold soup or porridge,4,5 although others6,7 have called them “pies.” A close look at the painting gives a clear idea of bowls containing liquid.

Most meals of Netherlandish peasants were porridge or “a mush of grains” and some root vegetables; “meat and spices were rare.”8 The Harvest (or The Corn or Wheat Harvest, 1565), has people eating from bowls of milk containing pieces of bread, and others in the distance gathering fallen apples.9 In The Haymakers (also 1565), peasants have collected baskets of vegetables and berries.10 The Gloomy Day, probably a day in late February or early March at Carnival time close to the start of Lent, shows a boy eating a waffle.11

One of Bruegel’s masterpieces, The Netherlandish Proverbs (1559), illustrates nearly 120 proverbs.12 Fifteen of them concern food or eating. For example, we find “What good is a beautiful plate if there is nothing on it?” “To throw a smelt to catch a cod” (to make a small sacrifice for a bigger gain), “He who has spilt his porridge cannot scrape it all up again,” and “Horse droppings are not figs” (do not be fooled).

The peasant worked hard and prayed for sufficiency. He dreamt of abundance and feared famine. Bruegel represented these last two conditions in two “kitchen drawings.” In The Fat Kitchen (De Vette Keuken), fat people (and their fat dogs) stuff themselves with sausages, roasted meats and fowls, pig heads, and cheeses. Joints of meat hang from the ceiling. “Swine-like children” eat from a trough. A fat woman with large breasts nurses her baby. These gluttons do not let an emaciated man enter their fat kitchen.13,14 The Thin Kitchen (De Magere Keuken) has scrawny people in ragged clothes fighting over a turnip, a carrot, and a bowl holding a few mussels. The cupboards are bare. An emaciated woman with “wilted breasts” has no milk for her infant.15,16 The depiction of these contrasting “kitchens” is often felt to be a social comment, a “moralizing” on the economic inequalities of society.17 It may be, however, that one kitchen represents Shrove Tuesday (also called “Pancake Tuesday,” “Mardi Gras,” “Carnival,” or “Fastnachtsdienstag”), a day of eating a celebratory meal before the start of Lent. Lent is the “thin kitchen,” in which certain foods are given up.18

A representation of these two opposites is seen in the more obvious Battle (or Combat or Fight) Between Carnival and Lent (1559). “Carnival” is portrayed by a fat man sitting on a barrel, holding a skewer with a pig’s head, sausages, and a chicken. The “Lenten figure” seems to be a thin woman, holding a baker’s paddle with only two dried fish on it.19 Food has uncomplicated as well as symbolic meaning in Bruegel’s “unidealized scenes of peasant life.”20

References

- Radio New Zealand. “Snail water, beans and pies: Tasting 17th century foods via art.” March 25, 2018. https://www.rnz.co.nz/national/programmes/sunday/audio/2018637691/snail-water-beans-and-pies-tasting-17th-century-food-via-art.

- Maryan Ainsworth and Keith Christiansen, eds. From Van Eyck to Bruegel: Early Netherlandish Painting in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1998.

- Rose-Marie Hagen and Rainer Hagen. Bruegel: The Complete Paintings. Köln, Germany: Taschen, 2005.

- Magda Michalska. “Come dine with art history: Famous feasts in art.” Daily Art Magazine, May 13, 2023. https://www.dailyartmagazine.com/come-dine-art-history-cooked/.

- Hagen and Hagen, The Complete Paintings.

- Charles Cuttler. Northern Painting: From Pucelle to Bruegel/Fourteenth, Fifteenth, and Sixteenth Centuries. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc.,1973.

- Radio New Zealand, “Snail water.”

- Radio New Zealand, “Snail water.”

- Ainsworth and Christiansen, Van Eyck to Bruegel.

- Hagen and Hagen, The Complete Paintings.

- Bob Claessens and Jeanne Rousseau. Bruegel. New York: Portland House, 1987.

- Hagen and Hagen, The Complete Paintings.

- Hans Liefrinck I, after Pieter van der Heyden, after Pieter Bruegel the Elder. The Fat Kitchen. 1563 or later. Sheet (trimmed to plate mark): 21.8 x 28.2 cm (8 9/16 x 11 1/8 in). National Gallery of Art. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.47638.html.

- Lisa Strickland. “Reforming Bruegel: Between the margins of morality and the confines of comedy.” Thesis. Stony Brook University, 2012. http://hdl.handle.net/1951/59876.

- Strickland, “Reforming Bruegel.”

- Fitzwilliam Museum. Feast & Fast: The Art of Food in Europe, 1500–1800. University of Cambridge, November 26, 2019 – August 31, 2020.

- Kim Andringa. “Les gras et les maigres: Camille Lemmonier, Pieter Bruegel et la cuisine sociale.” Études Germaniques 286(2), 2017.

- Strickland, “Reforming Bruegel.”

- Strickland, “Reforming Bruegel.”

- Ainsworth and Christiansen, Van Eyck to Bruegel.

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Leave a Reply