JMS Pearce

Hull, England

A forensic autopsy performed to establish the cause of death is an ancient practice.1 In Europe it was preceded by conventional pathology, as started by Herophilus of Chalcedon (335–280 BC). Medicolegal autopsies to solve legal problems were first performed in Bologna in 1302. During the Middle Ages, physicians’ opinions were sought to determine questions of fact in judicial proceedings.2 However, at this time Chinese forensic medicine was far in advance of European practice.1

The scope of forensic medicine gradually widened. By the end of the sixteenth century, civic authorities would sometimes request medical evidence to help solve fatal crimes. Toxicology and institutes of forensic medicine began to emerge.3 The office of coroner is mentioned in the Athelstan charter to Beverly in 9254 with duties to regulate civic offenses and felonies, as in the Magna Carta of 1215. In 1877 a law was enacted requiring a coroner’s inquest to be conducted in cases of violent or unnatural death. In Britain, before the eighteenth century, forensic autopsies were not commonly performed. Thomas Wakley, the editor of The Lancet, was a prominent coroner who founded the “Medical Witnesses Remuneration Bill” in 1836.5 Mathieu Orfila (1787–1853) analyzed the chemistry of human fluids and tissues to detect disease and advanced the science of toxicology.6 Edmond Locard (1877–1966) was a pioneer in forensic science in France.

Departments of forensic medicine and textbooks increased.1 Samuel Farr published the first English book on legal medicine in 1788.7 Andrew Duncan was first Regius Professor of Forensic Medicine at Edinburgh in 1807. In 1813, James S. Stringham was appointed Professor of Medical Jurisprudence in New York. Ten years later Theodoric Romeyn Beck, also a New York physician, published his Elements of Medical Jurisprudence. Professor Alfred Swaine Taylor of Guy’s Hospital published Principles and Practice of Medical Jurisprudence in 1865. He acquired fame as an expert witness in many Victorian cases of fatal poisoning.

In the nineteenth century, poisons were readily available, contained in household goods such as wrapping paper, toy paints, and clothing (hence Agatha Christie’s Arsenic and Old Lace), and also in chemicals used in gardening and farms. Arsenic and strychnine were the favorite poisons. Dramatic newspaper reports of criminal trials created a demand for more expert forensic toxicologists to assist investigations of violent crimes, poisoning, and deaths.

Although there were many new chairs of medical jurisprudence, Victorian forensic medicine struggled to achieve respectability. Doctors could not reliably distinguish between homicide, suicide, and natural or accidental deaths. Forensic evidence therefore often appeared confusing or ill-founded; trials fell into disrepute. At the dawn of the twentieth century, St. Mary’s Hospital London became a stronghold where Stevenson, Pepper, Luff, and Willcox, by employing more objective methods, managed to restore some of its prestige.

But it was their pupil Bernard Spilsbury who radically changed public perception. Forensic autopsies, he insisted, should be used to determine whether death was due to natural or to other causes. The investigation of the scene and circumstances of a death were essential. He thus persuaded Scotland Yard detectives of the need for forensic medicine specialists at murder scenes and was appointed the Home Office Pathologist for Scotland Yard in 1908.8 In America the FBI established the first complete crime laboratory in Los Angeles in 1923.

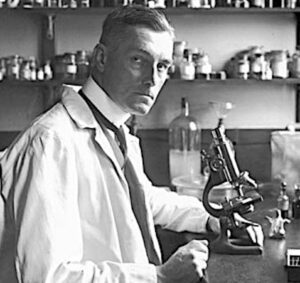

Sir Bernard Henry Spilsbury

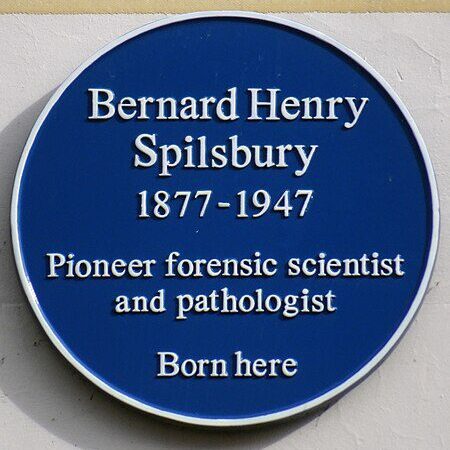

Bernard Henry Spilsbury (1877–1947) was born at 35 Bath Street, Leamington Spa, Warwickshire (now the shop of Birk & Nagra pharmacists), the eldest of the three children of James Spilsbury, a chemist, and Marion Elizabeth Joy. He was educated at Leamington College, University College School, Manchester Grammar School, Owens College, then Magdalen College Oxford.9 In 1899 he graduated BA in natural science and began medical studies at St. Mary’s Hospital London where he was greatly influenced by AJ Pepper, AP Luff, and Sir William Wilcox, the Home Office criminal investigation experts. In 1905 he qualified in medicine although his academic performance was unexceptional.

At St. Mary’s, Arthur Pearson Luff had written a Textbook of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology (1895); Sir William Willcox (aka the Detective-Physician) even before WW1 had testified in twenty-five trials for murder or manslaughter. The third man to excite his interest was Augustus Joseph Pepper. Spilsbury worked under Pepper as assistant demonstrator of pathology (1904–5) and as pathologist, succeeding Pepper when he retired in 1908.9

Spilsbury passed the MRCP and was elected FRCP in 1931. He lectured and was examiner on forensic medicine and toxicology at St. Mary’s, St. Bartholomew’s, and several London teaching hospitals.

He acquired renown as a forensic pathologist and brilliant expert witness in a series of notorious murder cases. Assiduous in conducting accurate, detailed investigations, his presentation in court was authoritarian, concise, and easily understood by jurors. Never over-awed, under cross-examination he dominated proceedings and won immense respect from counsel, judges, juries, and the public.9

The Crippen case of 1910 secured his fame, rapidly followed by other criminal investigations, which enhanced his prestige. Hawley Harvey Crippen was an American doctor accused of poisoning his wife, Cora (Belle Elmore). Only partial human remains were found in the cellar of their house. Pepper’s autopsy and Spilsbury’s microscopic analysis identified the remains as those of Cora Crippen, who had been poisoned by hyoscine, then dismembered. A crucial factor in proving Crippen’s guilt was the examination of a small fragment of a hysterectomy scar with which Spilsbury established Cora Crippen’s identity. His testimony ensured Crippen’s conviction and execution.9

Frederick Henry Seddon in 1911–12 was accused of administering arsenic to Eliza Barrow, from whose death he expected to profit financially. Spilsbury, countering an arduous cross-examination, held that Barrow had died from acute poisoning rather than chronic medicinal arsenic consumption. This proved decisive. Seddon was found guilty and hanged.

In the “Brides In The Bath” case of 1915, Spilsbury helped to convict George Joseph Smith. In three consecutive marriages, each of his newly-married wives had died in the bath. Rejecting the defense’s proposal of accidental drowning or illness in the bath, Spilsbury produced the bath in court and dramatically demonstrated how Smith had drowned his brides. This convinced the jury of his guilt and he was hanged.

Herbert Rowse Armstrong, a solicitor, was tried in 1922, suspected of poisoning his wife with arsenic. Spilsbury’s evidence again led to a conviction. A striking feature of the trial was a glowing tribute given to Spilsbury by the judge, Mr. Justice Darling reported in The Times.

Spilsbury was knighted in 1923, renowned not only as an exceptional witness but as a pathologist who helped to establish forensic science as a profession.10,11 Jurors seldom questioned his conclusions. Barristers were rarely able to refute his opinion on forensic medical issues. Indeed, newspapers suggested that the appearance of “Sir Bernard in the Box” was a crucial point.

His reputation for invincibility, not surprisingly, provoked criticism.9 The most controversial issue was in 1925 when Norman Thorne was accused of fatally beating Elsie Cameron at his chicken farm and trying to make her death appear as suicide. The defense conceded that Thorne had concealed the body, but argued she had hung herself with a clothesline. Several medical witnesses were arrayed against Spilsbury, who found no rope burns on the neck and contended on uncertain evidence of internal bruising12 that she had been beaten to death. The jury sided with Spilsbury. Thorne was executed.

As a sequel to this trial, Spilsbury’s “papal infallibility” was seriously questioned by the press and by Conan Doyle, Edgar Lustgarten, and the Law Journal. Sydney Smith described him as “extremely smart and highly famous, but fallible, and very, very obstinate.”

His authority, now challenged and sullied, was based on his unrivalled experience of cases of poisoning, deaths due to firearms, illegal abortions, suicide, and asphyxia. In the 1930s, Spilsbury was performing between 750 and 1,000 post-mortem examinations each year.9 His notebooks included more than 6,000 medico-legal cases. In court he was conspicuously well dressed, and endowed with a confident, aristocratic bearing. His success was due not only to his experience and formidable power as a witness, but to his persuasive if austere courtesy. His friends noted him as a man of culture, who showed as much kindness to an articled clerk as to a promising young barrister.

He did little research, he trained no pupils, and he never wrote a textbook.

He advised British Naval Intelligence in the development of “Operation Mincemeat,” a deception conceived by Lieutenant Commander Ewen Montagu CBE QC and Flight Lieutenant Charles Cholmondely to fool the Germans about the true target for the Allied invasion of Sicily. It saved thousands of lives.

Spilsbury belonged to many prestigious London clubs and was president (1933–5) of the Medico-Legal Society. One of his most cherished associations was with a group of criminologists, writers, and forensic enthusiasts (still in existence) known as “Our Society” or the “Crimes Club.”

In 1908 he married Edith Caroline Mary Horton. They had four children. He worked with his sons Peter, who became a house–surgeon, and Alan, who assisted him in his laboratory. In 1940 Edith left him to live with her sister; in the same year he had a stroke, and another in 1945 from which he did not fully recover. The deaths of Peter in a bombing raid of St. Thomas’ Hospital in 1940, Alan from tuberculosis in 1945, and Constance his sister in 1942 grievously affected him.

He was found unconscious on 17 December 1947 in his gas-filled laboratory at University College, London; he could not be revived. The coroner recorded Spilsbury’s sadness concerning his declining health as a factor in his suicide. Lady Spilsbury, his son Richard, and daughter Evelyn survived him.

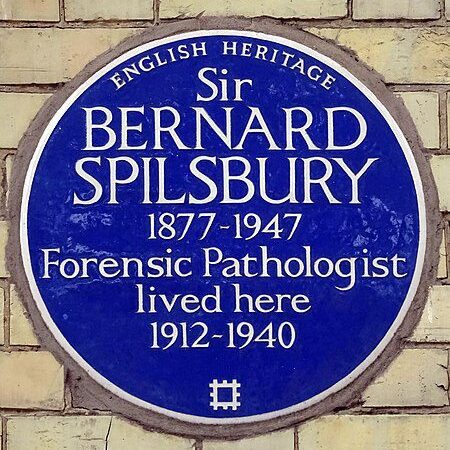

A father of modern forensic medicine has been honored with blue plaques in North London and one at his birthplace, now Birk & Nagra, chemists in Leamington Spa.

Others were to tread in the footsteps of Spilsbury and his eminent contemporary Sir Sydney Smith; foremost among them were professors Keith Simpson, Francis Camps, John Glaister, and CJ Polson.

References

- Smith S. The history and development of forensic medicine. British Medical Journal 1951;1:599-607.

- Payne-James JJ. Forensic Medicine, History of. In Encyclopedia of Forensic and Legal Medicine, Elsevier 2016; 2:539-44.

- Vanezis P. Forensic medicine: past, present, and future. The Lancet 2004;364:8-9.

- Carr JL. The coroner and the common law. I. Introduction. Calif Med. 1960 May;92(5):323-5.

- Cawthon E. Thomas Wakley and the medical coronership-occupational death and the judicial process. Medical History, 1986;30:191-202.

- Witthaus R. A. Becker T C. Medical jurisprudence, forensic medicine and toxicology. New York: William Wood & Company, 1894.

- History of Forensic Medicine & Pathology. https://pathology.med.sumdu.edu.ua/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Forensic-Medicine-Semantic-module1-History-of-Forensic-en.pdf.

- Browne DG, Tullett EV. Bernard Spilsbury – His Life and Cases. The Companion Book Club, 1952.

- Cawthon EA. Spilsbury, Sir Bernard Henry (1877–1947). In Dictionary of National Biography, OUP, 2004. https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-36217.

- Obituary. Sir Bernard Spilsbury MB FRCP. British Medical Journal 1947;2:1059.

- Polson CJ. Essentials of forensic medicine, London, English U.P., 1955.

- Burney I, Pemberton N. Bruised witness: Bernard Spilsbury and the performance of early twentieth-century English forensic pathology. Med Hist. 2011;55(1):41-60.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.

Leave a Reply