Jayant Radhakrishnan

Darien, Illinois, United States

Credit for pioneering heart surgery in children is primarily given to Robert Gross of Boston Children’s Hospital and Alfred Blalock at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. However, two Chicago surgeons who saved many lives with their innovations in the same era have been largely forgotten.

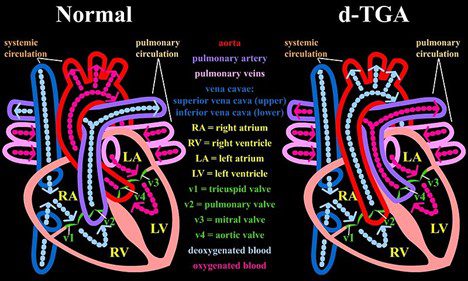

In the first half of the twentieth century, all so-called “blue babies” died. The two most common causes of this syndrome are tetralogy of Fallot and transposition of the great arteries (TGA). Both conditions occur in 1–5 per 10,000 births. Drs. Potts and Baffes concentrated on dealing with these two conditions.

Dr. Willis J. Potts (1895–1968) was the first chief of surgery at Children’s Memorial Hospital in Chicago. He started the second pediatric surgery training program in the US and wrote two uniquely empathetic books, The Surgeon and the Child and Your Wonderful Baby. In World War I, he served as a sergeant in the US Army. He later became a doctor and then a general surgeon . Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, at forty-seven years old he signed up to work in the Pacific sector at the 25th evacuation hospital from 1942 to 1945. After World War II, he became a pediatric surgeon and chief of surgery at Children’s Memorial Hospital.1

His intellectual integrity and technical excellence were recognized by all. Residents in his program had to develop competence in the animal laboratory before they were permitted to operate on patients. He demanded that they handle tissues with great gentleness with sayings such as “If you sponge the wound and the baby wiggles, you’re sponging too hard!” and “Treat the tissue like a case of acute orchitis—that is yours!”2 A deeply religious man, he tackled complex ethical issues that arise in caring for the incurably deformed at a time when no one else was doing so.1 He was also known to sing hymns in the operating room that would reflect how the operation was progressing: “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” when the operation was difficult and “Jesus Loves Me” when the procedure was progressing well.3

In 1945, Dr. Helen Taussig’s concept of creating an anastomosis between the systemic circulation and the pulmonary artery in tetralogy of Fallot4 was proven valid when Alfred Blalock and Taussig presented results of a palliative shunt in three patients with the condition.5 Potts embraced this with great enthusiasm. In time, though, it became apparent that in the smallest babies, who needed the shunt the most, the miniscule subclavian artery would impede blood flow into the pulmonary artery. It also resulted in clotting at the anastomosis. Furthermore, while use of the left subclavian artery for the anastomosis did not put the arm at risk of ischemia, on the right side, use of the innominate artery created a risk of inadequate cerebral blood flow. Hence, Potts set forth to devise a more direct shunt from the aorta to increase pulmonary blood flow. On September 13, 1946, Potts and Sidney Smith successfully anastomosed the aorta and pulmonary arteries side-to-side in an eighteen-month-old girl who lived to be sixty-two years old, thanks to the operation.2,6 Eventually, the Potts shunt fell out of favor because surgeons had trouble estimating the correct size for a given patient. If they made it too small, it was ineffective, while too large a shunt flooded the pulmonary system. In addition, intracardiac surgery to correct tetralogy of Fallot had become available by then.

Interestingly, the Potts shunt has recently been revived as a palliative procedure for patients with idiopathic pulmonary artery hypertension. In these patients, blood flows in the reverse direction, from the pulmonary artery to the aorta with the shunt acting as a popoff valve.7

Since paraplegia may be caused by total occlusion of the thoracic aorta when constructing the anastomosis, Potts and Smith devised an aortic exclusion clamp from an eyelid retractor. By excluding the medial lip of the descending thoracic aorta, this clamp gave them a dry anastomotic site while blood flow continued down the aorta. Some other vascular instruments Potts devised with his neighbor in Oak Park, Bruno Richter, were angled vascular scissors and fine-toothed vascular clamps that penetrate the vessel wall without crushing it. The teeth also prevent the clamp from slipping off the vessel. Other instruments he designed were a malleable two-fingered infant lung retractor and dissecting scissors with blades that had sharp points and beveled outer edges to separate delicate tissues without putting pressure on structures under it. He also devised a transventricular pulmonary valvulotome that could be opened and closed inside the ventricle. This permitted it to be inserted and removed through a small puncture wound in the ventricular wall.2 In 1954, he was the first to successfully operate on a pulmonary artery sling.8

Thomas G. Baffes (1923–1997) was born, raised, and completed medical school in New Orleans. He taught at Tulane from 1948 to 1952 before moving to Chicago and meeting Dr. Potts.

The other common and lethal congenital cardiac anomaly was transposition of the great arteries (TGA), now classified as dextro-transposition of the great arteries (D-TGA). In this group, babies survived only if they had a natural shunt such as a ventricular or atrial septal defect; it was best if both defects were present. Based on this observation, Baffes conceived of the idea of creating a shunt between the inferior vena cava (IVC) and the left atrium while also transposing the right pulmonary veins to the right atrium for partial correction of the transposed pulmonary artery and aorta. He chose to use the IVC since its location prevented it from being compressed by any other thoracic structures. The IVC also returns about the same amount of blood to the heart as that delivered by the right pulmonary veins. He approached Dr. Potts, who considered the idea carefully and then accepted it enthusiastically. Potts gave Baffes free rein to work in the dog laboratory and even obtained funds for the work.2 Synthetic vascular grafts were not available in those days, so they started by developing procedures to reliably harvest and sterilize human aortic homografts. The grafts were freeze-dried and vacuum-packed for preservation. To ensure that the bypass was of sufficient size to accommodate growth of the patient, Baffes operated on puppies and observed the shunt’s function until the dogs were full grown. During these studies, he also identified the vital role the azygos venous system played in permitting collateral flow, especially when a small aortic homograft was used.9 Baffes carried out the first such operation on May 6, 1955, and in 1960 he reported the results of this operation in 117 patients. In the first year, 50% of the patients died, but by 1959 the mortality rate had dropped to 8.3%.10 In the following years, Baffes along with Potts, William Riker, and Arthur DeBoer carried out the procedure in some 200 patients.2

At about the same time, the trans septal baffle procedure for atrial correction of transposition was developed by Albert in the laboratories of Children’s Memorial Hospital and by Mustard in Toronto. Baffes and his colleagues modified the Mustard procedure to make it the second stage in correction of the transposition in patients with a previous Baffes procedure. They carried out the procedure in seven patients, five of whom survived.11 Open-heart surgery became available soon after and total correction of TGA became the norm.

Baffes came up with one more impressive innovation by re-examining pathology specimens of TGA. He noticed the close relationship of coronary ostia to the ascending aorta and devised the technique of “triangulation” of the sinus of Valsalva to transfer coronary arteries to whichever great vessel was attached to the outflow tract of the systemic ventricle without kinking the coronary vessels.12

In those early days, hospitals did not have extracorporeal circulation available, so Baffes and his colleagues purchased a heart-lung machine and carried it in the trunk of Baffes’ car from hospital to hospital to treat patients.13 Also consistent with his innovative thinking was his use of extracorporeal support after cardiac surgery in infants, years before extracorporeal cardiac and respiratory support was described by Bartlett.4,14

Baffes became the chief of surgery at Mount Sinai Hospital, Chicago and later obtained his law degree at DePaul University. He was a member of the law firm Pierce, Daley, Baffes & O’Sullivan, which represented physicians accused of medical malpractice. In addition, he continued to teach at the DePaul University Law School. In 1990, Children’s Memorial Hospital and one of his grateful patients, who became a general surgeon, recognized his extraordinary career by instituting a visiting lectureship in his name.

When Dr. Baffes retired, he passed on neatly handwritten index cards in which he recorded salient details of every patient he had ever treated. Those of us who had the privilege of following up any of his patients noted his exquisite results. The gratitude of his patients was obvious.

Both these surgeons deserve to be remembered because they saved children who were destined to die within months, and because their contributions led to therapeutic modalities that are currently being used to correct congenital cardiac anomalies.

References

- Raffensperger J. Potts and Pott. Hektoen International Surgery/Chicago medicine, Summer 2020. https://hekint.org/2020/07/08/potts-and-pott.

- Baffes TG. Willis J. Potts: His contributions to cardiovascular surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 1987;44:92-96.

- Snider A. Big hands, small hearts. Corpus Christi Times, November 11, 1965.

- Radhakrishnan J: Unconventional wisdom. Hektoen International Surgery, Spring 2023. https://hekint.org/2023/04/13/unconventional-wisdom-a-risky-business/.

- Blalock A, Taussig HB. The surgical treatment of malformations of the heart in which there is pulmonary stenosis or pulmonary atresia. JAMA. 1945;128(3):189-202.

- Potts WJ, Smith S, Gibson S. Anastomosis of the aorta to a pulmonary artery; certain types in congenital heart disease. JAMA 1946;132(11):627-631. doi: 10.1001/jama.1946.02870460017005.

- Baruteau A-E, et al. Potts shunt in children with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: Long-term results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94(3):817-824. doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.03.099.

- Potts WJ, Holinger PH, Rosenblum AH. Anomalous left pulmonary artery causing obstruction to right main bronchus: report of a case. JAMA 1954;155(16):1409-1411. doi: 10.1001/jama.1954.73690340007008c.

- Baffes TG. A new method for surgical correction of the aorta and pulmonary artery. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1956;102:227-233.

- Baffes TG, et al. Surgical correction of transposition of the great vessels: A five-year survey. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1960;40(3):298-309.

- Baffes TG, Fridman JL, Patel KE, Bicoff P. Mustard procedure as a second stage for total correction of transpositions with previous Baffes operation. Ann Thorac Surg 1971;11:113-121. doi.org/10.1016/S0003-4975(10)65424-0.

- Baffes TG, Ketola FH, Tatooles CJ. Transfer of coronary ostia by “triangulation” in transposition of the great vessels and anomalous coronary arteries: A preliminary report. Dis Chest. 1961;39:648-655. doi.org/10.1378/chest.39.6.648.

- Mavroudis C, Backer CL, Siegel A, Gevitz M. Revisiting the Baffes operation: It’s role in transposition of the great arteries. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:373-377. doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.07.131.

- Baffes TG, Fridman JL, Bicoff JP, Whitehill JL. Extracorporeal circulation for support of palliative cardiac surgery in infants. Ann Thorac Surg. 1970;10(4):354-363.

JAYANT RADHAKRISHNAN, MB, BS, MS (Surg), FACS, FAAP, completed a Pediatric Urology Fellowship at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, following a Surgery Residency and Fellowship in Pediatric Surgery at the Cook County Hospital. He returned to the County Hospital and worked as an attending pediatric surgeon and served as the Chief of Pediatric Urology. Later he worked at the University of Illinois, Chicago, from where he retired as Professor of Surgery & Urology, and the Chief of Pediatric Surgery & Pediatric Urology. He has been an Emeritus Professor of Surgery and Urology at the University of Illinois since 2000.

Leave a Reply