Göran Wettrell

Lund, Sweden

William Osler was one of the most famous physicians and medical teachers of his time. He combined a wide knowledge of clinical medicine and science with humanity and approached patients and people in a humoristic and enthusiastic way.1

Osler has been called “the Father of Modern Medicine.” He revolutionized the teaching of medicine, liberating medical students from lectures in the classroom and bringing them into the wards for bedside teaching. He ranked high as a writer and speaker, was familiar with many and various subjects, and felt it was the duty of every medical man to contribute to the progress of medicine. He said: “We are here to add what we can to life, not to get what we can from life.” During his Oxford years, he revised several editions of his magnum opus, The Principles and Practice of Medicine, the best source of information of his time on the science and practice of medicine.

Osler worked about thirty years in Canada and America at well-known universities. His association with Great Britain began from 1872–73 when he worked at London University College in the physiological laboratory under the late professor John Burdon-Sanderson. Until 1905 he made frequent visits in the summer months for rest and literary works, delivered special lectures (Goulstonian, Cavendish), and participated in special meetings.

Osler attended the annual meeting of the British Medical Association in Oxford during July 1904. On his return from a visit to Burdon-Sanderson, who had just resigned that year from the Regius Professorship of Medicine in Oxford, he put the humorous query to a friend: “Do you think that I am sufficiently senile to be a Regius Professor?”1 A few weeks later, on the sea voyage back to the US, he decided to accept the offer of Regius Professorship of Medicine in Oxford. Over the years, Osler crossed the Atlantic at least thirty-two times.2

Regius Professorship of Medicine at Oxford, 1905–1919

The Regius or King’s Professorships were founded in 1546 during Henry VIII’s reign. The chairs of Regius Professor were appointed by the Crown in conjunction with an advisory board from the university. This position for Osler at the age of fifty-six was expected to be less demanding than his work in Baltimore. Besides, he had considered anyway to move to England in order for his son Revere to attend school there. Already by the 1890s, he had written to a friend, “I have lost my heart to Oxford.”3

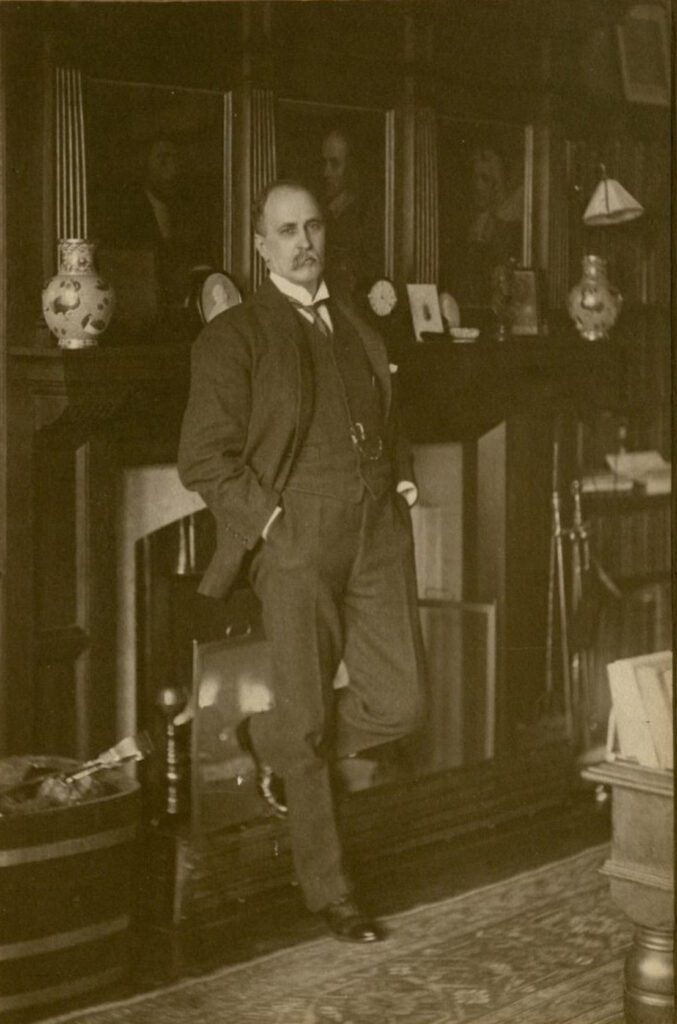

He arrived in Oxford in May 1905. His main duties were to examine candidates for the MD degree after they had trained in London, as Oxford had only a pre-clinical medical faculty. Coming to Oxford, Osler recognized the need to bring the academic teaching of medicine in touch with realities of practice. He showed interest in developing the departments of pathology and physiology and linking the scientific investigations to the clinical experience. The wards of the Radcliffe Infirmary, the local district hospital, were made available for Osler as an active consultant. Every Sunday morning at ten o’clock sharp during the term, Osler made ward rounds, often with kind and cheery words for some of the medical students, ward sisters, or the patients. He also conducted weekly clinics, which attracted the medical Oxford practitioners, the medical assistants, and the medical students, who received special instruction in physical diagnosis. Some of his clinical proverbs can be summarized as: “Get the patient in a good light. Use your five senses. We miss more by not seeing than we do by not knowing. Always examine the back. Observe, record, tabulate, communicate.”1 After work, he would sometimes invite the students to his house for an evening in the library to tell them the story of Harvey, Laennec, and Auenbrugger, and to show them various editions of works of these men (Figure 1). His behavior was encouraging for young fellows who admired him as a master—a scientist, a scholar, a humanitarian, and a philosopher, all in one physician.

For the development of the Radcliffe Infirmary, Osler participated in staff meetings and acted as an inspiring chairman. He raised funds to modernize the laboratories at Radcliffe Infirmary, and he himself was extraordinarily well trained in pathology and clinical microscopy. The hospital was also, due to personal effort of Osler, working with a tuberculosis dispensary, taking an integrated part in the treatment and prevention of tuberculosis. When discussing the use of morphine with a colleague in hopelessly ill tuberculosis patients, Osler called morphine “G.O.M.” (“God’s own medicine”). He based his use of drugs on empiricism, halfway between the generous use of drugs on one hand and a therapeutic nihilism on the other.1

The Regius Professor of Medicine (RPM) at Oxford was also made a fellow of Christ Church College, with access to delightful rooms. Osler dined there on Sunday night, often with guests in the Hall of the College. As RPM, he was also a Master of Ewelme holding tenure of the old farmhouse. Osler was kind and engaging to the old almsmen and pensioners living in the Ewelme almshouses near Oxford. He and Lady Osler were always delighted to take visitors to this peaceful and isolated country retreat.

Outside his medical work, Osler’s greatest interest in Oxford lay in the Bodleian Library. It brought him leisure and opportunity.4 As RPM he was one of the eight curators of the library and spent much of his leisure time there. His memory of old and new books was remarkable . In his half hours of reading in bed every night for forty or fifty years, he covered everything, poetry and prose, and retained it all. He was appointed a delegate of the institution of Clarendon Press, where the fine art of printing of books was implemented. His bibliographic knowledge contributed greatly. He founded and edited the Quarterly Journal of Medicine by Oxford University Press and directed wisely the series of Oxford Medical Publications. He appreciated the value of medical books, as expressed in his proverb: “To study the phenomena of disease without books is to sail an uncharted sea, while to study books without patients is not to go to sea at all.”

Figure 2. Entrance of 13 Norham Gardens, 2021. It is today home to the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, the Osler-McGovern Centre, and Osler’s library as preserved by Green Templeton College. Photo by author.

William Osler’s knowledge on medical questions and matters of education was extensive. There was hardly any committee in the region that did not have him as its active member. He had a deep interest in the Royal College of Physicians and often went to London to participate in their meetings. He was present at the memorial meeting, the Darwin-Wallace Commemoration, 1908, at the Linnean Society in London, describing the occasion as “intensely interesting, particularly to see and hear such veterans as Hooker and Wallace.”5 As a post-graduate, he had seen Darwin once at the Royal Society reception in the 1870s and had described him as” a most kindly old man, of large frame, with great bushy beard and eyebrows.”5 Darwin-Wallace’s contributions were originally read at a meeting of the Linnean Society on 1 July 1858 and published as a “joint paper” on 20 August of that year. After the formal Meeting at the Linnean Society in 1908, Osler received an extra copy of the Proceedings of the Society from 1858. He had it bound separately for his library and described it “as containing the two most fruitful contributions to science made in 19th century; contributions which have revolutionized modern thought.”5 Osler was an ardent bibliophile.

During the First World War, Osler was a Civilian Member of the committees of the War Office and paid weekly visit as a medical consultant to several military hospitals. During the war, he made a point of visiting as far as possible all the American and Canadian hospitals in the southern part of England.1

The Osler house at 13 Norham Gardens

On arriving at Oxford in spring of 1905, the Osler family moved to 7 Norham Gardens, the home of a previous Regius professor . From the start, many friends from Great Britain, America and Canada came to meet him there. In early 1907, the family moved to 13 Norham Gardens, which needed alterations that took several months of struggle (Figure 2). In September 1907, Osler wrote the following: “The garden is a great delight. We have had tea on the terrace every afternoon for the past fortnight [(Figure 3)]. The ‘hotel’ is opened up and we have had a succession of old friends.” The “hotel” became famously known as “the Open Arms,” a house of hospitality and friendship.1 Over the years, Osler and his wife, Grace Revere Osler, frequently opened their home and hosted a long procession of visitors, including relatives, medical students, colleagues, and friends from nearby and overseas. Many Americans called on him during the war and referred to him as the “Ambassador of North America.” Lady Osler had her maid keep a record of visiting Americans to whom tea had been served during the war period, and the number was over sixteen hundred.1 The total number of visitors to the residence was in the range of six thousand.3 Many visitors to England made a point of two things—“seeing Shakespeare’s birthplace and calling on Osler at Oxford.”1

The coronation of King George V took place in June 1911. A long list of coronation honors, among them twenty baronets, Osler included, was published that year. Already in the afternoon, on 11 June, 13 Norham Gardens was full of people. Dr. Osler walked in with a letter and threw it to his wife. It was from 10 Downing Street and marked “Confidential.” When they had an opportunity for a moment alone, she said, “What excuse are you going to give for declining it; you always have said you would,” and he replied, “I think I’ll have to accept—Canada will be so pleased—there is only one Canadian baronet.”6 People felt that it was a well-deserved honor. The President of the Royal College of Physicians described him as a peacemaker and a binder-together of the different interests of medicine, both at home and abroad.1

When meeting a young fellow or student, Osler had a way of making them think of him as a student, though a much senior one. A medical student, Wilburt C. Davison, had an appointment at 13 Norham Gardens to discuss his study plan.1 Somewhat terrified, he rang the doorbell, and to his surprise, Sir William Osler himself answered and, with one arm around the student’s shoulders, propelled him into the drawing room and presented him to Lady Osler as “the latest American colt.” Davison was assured of his plan for the medical courses and was invited to tea for the following Sunday.

Osler’s interest in historical medicine became an important part of the medical training at Oxford. At intervals throughout the year, he would invite six or seven of the medical students to his home. After dinner he would bring into the room an armful of his old and precious editions to show and explain them to the students (Figure 1). Then he would tell the students about the lives and contributions of Sydenham, Avicenna, and Paracelsus.1

Another medical student, Wilder Penfield, when visiting 13 Norham Gardens, was first addressed by the butler in a conventional way.1 Then, Lady Osler, with a smile, said welcome and added, “Sir William is over here on the floor.” At the end of the room a young officer was stretched out on the floor and Sir William, on his knees, was bandaging an imaginary wound on him with a pocket handkerchief. The explanation of the strange scene was found in the ecstatic applause of two little children nearby, who called the kneeing man William—he seemed to be a beloved companion. Osler had a lifelong love of children and a unique ability to win their trust and affection. He frequently advised the young students to make friends with children in order to keep their own minds young.

In April 1916, Wilder Penfield, the later well-known neurosurgeon, was injured with a broken leg when his warship Sussex was torpedoed.1 He was first taken care of at the military hospital in Dover. As soon as traveling was possible, he was brought to the Osler family at 13 Norham Gardens to complete his convalescence as a member of the family. He enjoyed the Osler family support and had the opportunity to recover on the terrace outside the library of the house, looking at the beautiful spring-like garden combined with reading of selected books, all chosen by Sir William (Figure 3).

Sir William Osler’s last days in Oxford

Overworked and sadly stricken by the loss of his son Revere during the war in 1917, Osler worked in Oxford hard “to do the day’s work well and not to bother about the future.” Before leaving the US in 1905 he had declared at the farewell dinner some other personal ideas such as “to cultivate a measure of equanimity in order to bear success with humility, the affection of friends without pride, and to greet sorrow and grief with courage.”7 He gave his last public address, entitled “The Old Humanities and the New Sciences,” in Oxford in May 1919 as President of the Classical Association. He wisely focused his valedictory ideals in a Hippocratic spirit on a humanity based on the union of science and the healing craft for his fellow humans.8 William Osler practiced medicine as “a science of uncertainty and an art of probability” and shared the uncertainty with his patients ”to do the kind thing and do it first.”9

During the Spanish influenza epidemic in the autumn of 1919, he contracted an upper respiratory infection. Resolution was delayed, and he developed a local empyema and abscesses of the lung. A few days before the end he had surgery performed in his home with resection of a rib and drainage of pus. Left weak, he seemed to recover somewhat, but on 29 December, one of the abscesses ruptured, causing profuse bleeding into the pleural cavity. In the afternoon on 29 December 1919, he died in his home at 13 Norham Gardens. His funeral ceremony took place in the old cathedral linked and serving as the college chapel to Christ Church College. Osler had called Thomas Browne his lifelong “mentor” and his book Religio Medici a life-long “vademecum”. At the last service, a copy of his book had been placed on his coffin in the chapel.3 In accordance with his expressed desire and as a last gift, Sir William’s ashes were later deposited in the Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University, Toronto, in the midst of the books, in the Osler Niche of his beloved collection, Bibliotheca Osleriana.

In memory of Sir William Osler—he followed the golden rule.

References

- Sir William Osler. Memorial Volume. Bulletin No IX of the International Association of Medicine Museums. Edited by Maude Abbott, Montreal, Toronto. Murray Printing, 1926, p. 275-432.

- Bryan, C.S, and Fransiszyn, M. Osler usque ad mare: the SS William Osler. CMAJ,1999;161(7): 849-52.

- Sir William Osler: An Encyclopedia. Edited by Charles S. Bryan. Novato, California. Norman Publishing in association with the American Osler Society. 2022, p. 197, 548.

- Selected Writings of Sir William Osler. Edited by Alfred White Franklin and committee of the Osler Club of London. Oxford University Press. London. 1951, p. 266.

- Cushing, H. The life of Sir William Osler. Oxford University Press. London, New York, Toronto. 1940. Volume 2, 131-3.

- Ibid, p. 275-6.

- Wettrell, G. William Osler: clinician and teacher with a pediatric interest. Hektoen International, Physicians of Note, Fall 2020.

- Cushing, H. Consecratio Medici and other papers. V William Osler, the Man. Boston. Little, Brown and company. 1940, 116-7.

- Bryan, C.S. Caring Carefully: Sir William Osler on the Issue of Competence vs Compassion in Medicine. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings. 1999; 12(4): 277-84.

GÖRAN WETTRELL, MD, PhD, FLS, is an associate professor and senior consultant in pediatric cardiology and pediatrics at Lund University, Sweden. His work focuses on pediatric pharmacology, cardiac molecular genetics, and primary arrhythmias. Other interests include male choir singing, travel, and medical history.

Leave a Reply