Jill Kar

New Delhi, India

|

| Figure 1. Anandi Gopal Joshi (March 31, 1865 – February 26, 1887). Via Wikimedia. Public domain. |

Anandibai Joshee (Anandi) set sail from India at the age of eighteen. Bartering her bangles for books, she traded convention for an education, which was considered shameful in nineteenth-century India.1 In doing so, she was the first Indian woman to become a physician (Fig. 1).

Born to a traditional Hindu Brahmin family in Maharashtra, India in 1865,2 she was married off at the tender age of nine to a twenty-six-year-old widower and postal clerk.3 Her husband, Gopalrao Joshee (Gopal), a liberal man for his time, was supportive of women’s education. However, his deep-rooted patriarchal dominance still manifested itself, as Gopal would beat Anandi with firewood sticks and wooden chairs when she was not studying. “It is very difficult to decide whether your treatment of me was good or bad. If you ask me, I would answer that it was both. It seems to have been right in the view of its ultimate goal; but in all fairness, one is compelled to admit that it was wrong…It was too severe for the age, body and mind,” wrote Anandi in a heart-wrenching letter to Gopal years after the abuse. As a traditional Hindu wife and a child, she had no recourse but to allow this treatment.3(p.40),4 At fourteen years of age, she gave birth to a baby boy who died after ten days from a lack of medical care. This incident deeply affected Anandi and may have induced her desire to study medicine.5

She attended one of the Christian missionary schools in Bombay, as these were the only institutions to support women’s education at the time. Even though Bombay was slowly awakening to the possibility of reform, Anandi faced the cruel realities of being a Hindu wife going to school. Vendors and onlookers would shout comments, throw pebbles, and even spit on her as she walked to school. But nothing seemed to stop her. She became fluent in English and seven Indian languages. She traveled independently in a society where women rarely went out, and then only with a man.3(p.42)

Gopal soon realized that the only way to get Anandi the medical education she yearned for was to ask the missionaries for help. In 1878, he wrote to Dr. Royal Wilder, a renowned American missionary, expressing his interest in moving to the US for Anandi’s medical education. This letter was published in The Missionary Review and caused quite a debate. Wilder offered to help, but only if they converted to Christianity.5(p.33) This was unacceptable, and the couple’s hopes began to sink. But two years later, they received an unexpected letter. An American missionary named Theodicia Carpenter had spotted Gopal’s letter in an old issue of The Missionary Review at her dentist’s office in New Jersey. She was deeply moved by their story and decided to write to Gopal.3(p.43) Through such serendipity, Anandi’s life was about to change forever.

For the next two years, Anandi exchanged letters with Theodicia, talking about their distinct cultures, analyzing Hindu customs and the restraints they put on women while also condemning the rigid religious beliefs of the missionaries.3(p.44) Anandi was beginning to understand, reason, and express ideas about the world she lived in for herself. Theodicia offered to help and invited her to come to America. As Gopal could not afford passage for both of them, Anandi made the decision to go alone. “If this life is so transitory like a rose in bloom, why should one depend upon another?”5(p.71) she wrote to Theodicia, expressing newfound courage to defy old ordinances. This kind of decision was indeed phenomenal for a woman of that time. Backlash and name-calling followed, until she decided to take yet another remarkable step.

On February 24, 1883, Anandi made a powerful public speech on the subject: “My future visit to America and public inquiries regarding it.” She explained why it was important for her to study medicine abroad, highlighting the harassment she had faced during her education in India. She stated that she would not change her customs, mannerisms, food, or dress. “I will go as a Hindu and come back here to live as a Hindu,” she said.5(p.81-87) She promised that she would remain a strict vegetarian and dress herself in a saree (the traditional attire of Hindu women), much to the surprise of the missionaries, who had expected her to convert.3(p.46) She dreamed of returning to India to help her country-women receive better healthcare. This speech influenced many people and invited immense support for the courage she had displayed.

|

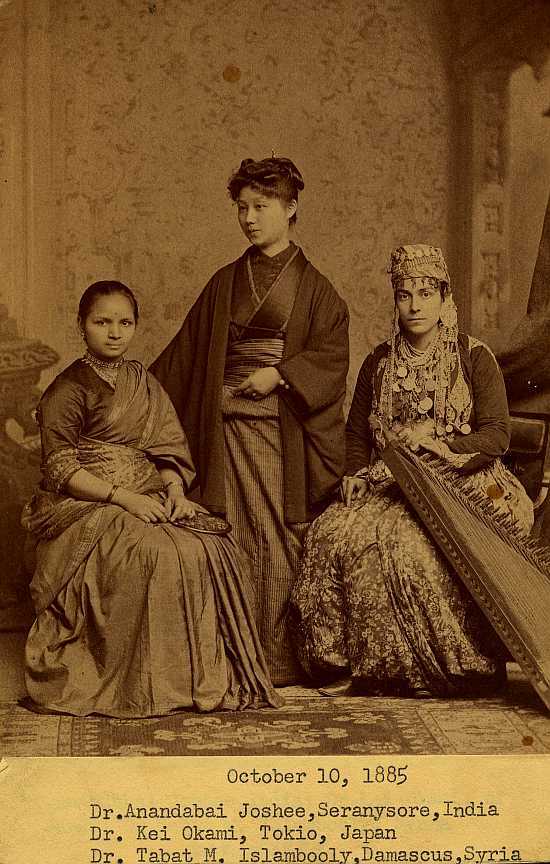

| Figure 2. Students of the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania at the Dean’s reception, 1885. Via Wikimedia. Public domain. |

To pursue her long-awaited dream of studying medicine, Anandi sold her bangles and used the money to finally set sail for America in April 1883,4(p.94) bridging the gap between her limitation and liberation. “The purpose for which I came is to render to my poor suffering country-women, the true medical aid they sadly stand in need of and which they would rather die than accept at the hands of a male physician. My soul is moved to help the many who cannot help themselves,” she wrote in her application to the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (now Drexel University).4(p.123) She graduated three years later with Kei Okami, the second woman doctor in Japan, and Sabat Islambooly, the first woman doctor in Syria.6 All three posed at graduation wearing their traditional attire. (Fig. 2)

Anandi was celebrated on her return to India. She was welcomed with the position of “lady-doctor” in-charge of the Albert Edward Hospital in Kolhapur, Maharashtra and teacher of medicine for young women. She was congratulated by Queen Victoria and the many Indian reformists of her time. But living this dream was cut short when she fell ill with tuberculosis and died in February 1887 at age twenty-two. Anandi’s ashes were sent to Theodicia, who interred them at Poughkeepsie, New York. Her gravestone reads “First Brahmin woman to leave India to obtain an education.”3(p.62-63), 4(p.1)

Although Anandi did not live to witness the pride she brought home, her death marked a beginning for many young Indian women who honor her legacy, which continues today as the Anandibai Joshi Award for Medicine7 and the Anandi Gopal Scholarship8 for young women.

References

- Kosambi M. Crossing thresholds: Feminist essays in social history. Permanent Black; 2007. p. 174.

- Karlekar M. Elusive voices: The lives and letters of Anandibai Joshi. Telegraph India, September 4, 2007. Accessed March 7, 2023. https://telegraphindia.com/opinion/elusive-voices-the-lives-and-letters-of-anandibai-joshi/cid/1027010.

- Rao K. Lady doctors: The untold stories of India’s first women in medicine. Westland Publications; 2021. p. 38.

- Kosambi M. A fragmented feminism: The life and letters of Anandibai Joshee. Routledge; 2020. p. 18.

- Dall C. The life of Dr Anandibai Joshi: A kinswoman of Pundita Ramabai. Roberts Brothers: Boston; 1888. p. 32.

- Falcone A. Remembering the pioneering women from one of Drexel’s legacy medical colleges. Drexel News, March 27, 2017. Accessed March 7, 2023. https://drexel.edu/news/archive/2017/march/women-physicians.

- India Today Web Desk. Who is Anandi Gopal Joshi to whom Google dedicated a Doodle? India Today, updated March 31, 2018. Accessed March 7, 2023. https://indiatoday.in/education-today/gk-current-affairs/story/who-is-anandi-gopal-joshi-to-whom-google-dedicates-a-doodle-1201625-2018-03-31.

- Dr. Anandi Gopal Scholarship Scheme. Symbiosis International (Deemed University), July 31, 2020. March 7, 2023. https://smcw.edu.in/assets/pdf/Dr-Anandi-Gopal-Scholarship-Scheme.pdf.

JILL KAR is a medical intern at Lady Hardinge Medical College, India. She is an avid writer, researcher, and reader. She is a former Ascona Awardee and possesses published work in medicine and ongoing projects in healthcare delivery and surgery.

Submitted for the 2022–23 Medical Student Essay Contest

Winter 2023 | Sections | Women in Medicine

Leave a Reply