Eve Elliot

Dublin, Ireland

“We don’t just borrow words; on occasion, English has pursued other languages down alleyways to beat them unconscious and rifle their pockets for new vocabulary.“

—James D. Nicoll

As any student of life sciences will tell you, medical terminology can feel like a foreign language. Fossae and foramina, erythropoietin and encephalomalacia, atelectasis and acromegaly—students have to assimilate an enormous number of Latin and Greek root words, suffixes, and prefixes to know that brachioradialis is called the “drinking muscle” for a reason, that eating ice cream can result in sphenopalatine ganglioneuralgia (brain freeze), and that unilateral periorbital ecchymosis is just a fancy way of describing a black eye.

Brevity may be the soul of wit, but it is vanishingly rare in the language of medicine—dimethylamidophenyldimethylpyrazolone is a kind of fever-reducing pain reliever; hepaticocholangiocholecystenterostomy is a surgical procedure involving the liver, gall bladder, and intestine; and the longest word in the medical dictionary is the forty-five-letter behemoth

pneumonoultramicroscopicsilicovolcanoconiosis (a lung condition caused by inhaling very small pieces of ash or dust).

It is enough to make you want to break down and lachrymate (cry).

Why do we do this to beleaguered students? Beyond the obvious need for precision and accuracy, there are other reasons medical language developed into a complex and formal lexicon of fifty-cent words.

Modern English is a sprawling, bloated language of at least 200,000 words in common usage, 35,000 of which are necessary for everyday communication. The size of the vocabulary comes from the peculiar English penchant for borrowing from other languages: by some estimates, up to 75% of English words have been lifted from somewhere else.

Old English, the collective term for several Germanic dialects spoken in the Anglo-Saxon age (roughly 500 to 1066 CE), forms the bedrock of modern English. The 100 most common English words are Anglo-Saxon in origin, including those describing family relationships (mother, father, brother) and body parts (shoulder, finger, belly), among other everyday things, not to mention most of our pithier swear words, too.

Anglo-Saxon medical terminology has largely vanished from modern usage, although here and there we do get glimpses of our Germanic past. The Old English word for healer was “læce,” which became leech; “sœcnes” meant sickness, and “unhæle” meant ill, which survived without the prefix to mean healthy, as in “hale and hearty.” Some of the more amusing terms now sadly lost to history are “flesh-strings” for muscles and “arse-ropes” for intestines.

Anglo-Saxon changed dramatically after the Norman conquest of England in 1066, when William the Conqueror established Latin-based French as the language of the Court. Old English and, later, Middle English remained the language of daily life, while French flourished in the arts and sciences, lending English various words for formal or official use. A classic example is the “beast or feast” rule for naming the animal or the (often extravagant) meal made from it—pigs became pork, cattle became beef, chickens poultry, and sheep mutton.

The medical arts followed suit, developing an unwieldy admixture of both tongues that drew on Anglo-Saxon for the everyday and Latin for the study and treatment of disease. To the modern scholar, it is not surprising that medical language adopted the more formal approach—it is hard to imagine describing oneself as a “leech” specializing in “arse-rope-craft”, after all—although we still use this hybrid system today; we consult a dentist for a sore tooth, see a dermatologist for dry skin, and an orthopedic surgeon for a broken leg.

Latin emerged as the dominant language of medicine largely because of the efforts of Roman aristocrat Aulus Cornelius Celsus, who compiled De Medicina, an encyclopedia of medical knowledge based on the work of Greek physicians such as Galen and Hippocrates. He discovered that many Greek terms, including compound words, could not be easily translated into Latin (erythrocyte meaning red cell in Greek would have been translated as the clunkier cellula rubra, for example) and that some Greek endings, such as -itis and -oma, were too usefully descriptive to abandon altogether. His solution was to simply incorporate them into the Latin terminology.

This resulted in a hybrid of both languages where a Latin word or root is used in some cases, Greek in another. Regarding the kidneys (from Middle English, “kidenei,” meaning “sac”), the convention is to use the Latin ren– for describing anatomy (i.e., renal duct), and the Greek nephr– for the specialty (nephrology). Sometimes a term itself is a hybrid, depending on whichever root and suffix combination were the easiest to use. Hypertension is a hybrid of the Greek hyper and the Latin tension, (supertension would have been the correct Latin term).

Occasionally, two words are used for the same thing. Epinephrine (epi-, above, nephr-, kidney) from the Greek is the same hormone as the Latin adrenaline (ad-, towards, near, ren-, kidney), and they are both classed as catecholamines (hormones that also act as neurotransmitters), which comes from a third language, Malaysian.

Or consider the interesting array of terms used to describe the anatomy, conditions, and specialties involving the lungs. Pulmo– or Pulmono- is Latin, Pneu- is Greek. Respiro- is Latin (not to be confused with the Greek spiro-, meaning spiral), and -ology is Greek. Pulmonology, then, comes from a mixture of Greek and Latin terms, as does respirology, both of which deal with breathing and lungs.

Perhaps Celsus’ greatest achievement, however, was in preserving the Greek tradition of naming anatomical structures after everyday items they resembled.

Some names were decidedly war-like in nature. Sella turcica, a depression in the sphenoid bone that shelters the pituitary, means “Turkish saddle.” The phalanges were named because of their resemblance to the formation of a Greek phalanx of soldiers. Thorax referred to a breastplate, galea a helmet.

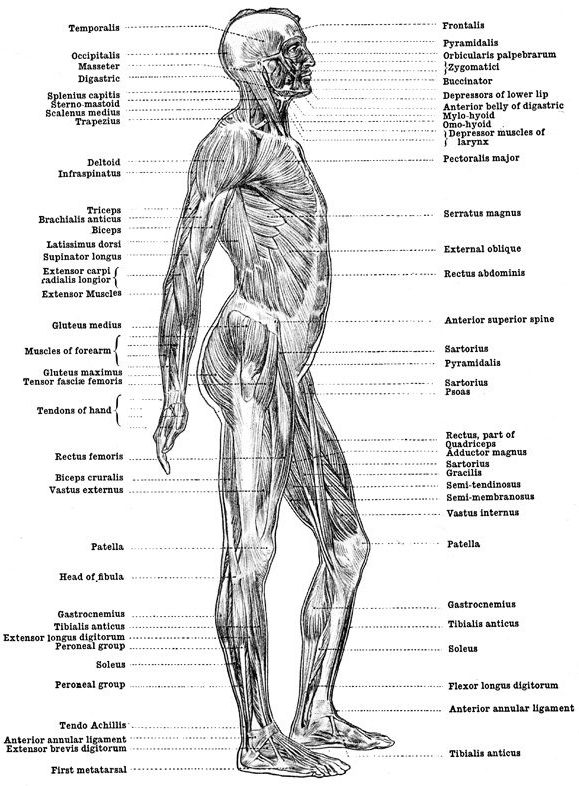

Other structures were named for animals or their behavior. Muscle comes from musculus, meaning mouse, because the movement of a contracting muscle beneath the skin reminded some ancient anatomist of a scurrying mouse. The distal end of the spinal cord resembled a horse’s tail and was named cauda equina. Pes anserinus, the tendinous attachment of the medial hamstrings, was so named because it reminded some long forgotten doctor of a goose’s foot (pes—foot, anser—goose).

Some parts of the body were named after simple household items. The cavity in which the head of the femur fits resembled an acetabulum, a flask used to hold vinegar; the kneecap looked like a patella, a flat pan; the slender, wispy fingers that just brushed the ovaries resembled the fringe on cloaks (fimbrae). Music was also a source of inspiration: the tibia (flute) was so named for the shin bones of animals that were used to make the instruments.

Plants gave us words such as uvea (grape), glans (acorn), and amygdala (walnut); geographical features gave us lacuna (pond, lake) and mons (mountain); arachnids gave us arachnoid (spider-like). Fishing nets (retinae and reticular) and seamstresses’ needles (fibulae) and pagan goddesses (iris, psyche)—the vivid imagery of the early anatomists is still with us today, even if much of the original meanings of the words have been all but forgotten.

Lest you think mastering Latin and Greek is sufficient to make you fluent in medical terminology, several other languages have contributed vocabulary over the centuries as well, most notably Arabic. Generally speaking, words of Arabic origin are used for common medical nouns, i.e., drug (deriaq), alcohol (alghol, meaning mind suppressor), cornea (cara’nia) and catheter (catha tair, or feather’s quill) but their use is widespread across the sciences—alkali (rich in kali, or potassium), algebra (al jebr, reunion of broken parts), degree (daraja), and cipher (sifr).

While precise, universal, and often fascinating, the use of formal medical terminology does, however, have its drawbacks.

In the 2008 study “The Role of Medical Language in Changing Public Perceptions of Illness,” Young et al found that using medical terminology in place of lay terms for common health concerns (erectile dysfunction disorder instead of impotence, sebhorreic dermatitis instead of dandruff, etc.) increased both patients’ and doctors’ perceptions of the seriousness and relative rarity of the condition, especially among common conditions that have recently become medicalized. Using medicalized terms like gastroesophageal reflux disease instead of heartburn has been shown to lead to greater emotional upset among patients who receive the diagnosis, especially given the use of the word disease.

And while some lay terms can still frighten patients who do not understand their actual meaning (heart failure does not mean the heart is about to stop altogether, although patients could be forgiven for thinking so), the increasing prevalence of medicalized terminology has the potential for lasting effects on the way health is promoted, advertised, and even sold to consumers.

Perhaps we ought to rethink our love affair with the language of antiquity and focus instead on the vernacular of the everyday, the lingua franca of the patients whose anatomy we are examining. Hippocrates and Galen made their observations in the common language of their day, after all; would we be doing them a disservice if we were to embrace our own instead?

But then again, would anyone seriously want to specialize in arse-ropes?

References

- Dexter A. How many words are in the English language? Word Counter. https://wordcounter.io/blog/how-many-words-are-in-the-english-language/. Accessed March 14, 2022.

- Nordquist R. Old English and Anglo Saxon. ThoughtCo. https://thoughtco.com/old-english-anglo-saxon-1691449.

- Burridge K. English, the language that lurks in dark alleyways. O&G Magazine. Published December 10, 2021. https://ogmagazine.org.au/23/4-23/english-the-language-that-lurks-in-dark-alleyways/. Accessed March 14, 2022.

- Vesalius Fabrica. An Anatomist at the Cutting Edge of History. https://vesaliusfabrica.com/en/vesalius/biography.html.

- Mangione S. Leonardo and the reinvention of anatomy. Hektoen International, Spring 2014. https://hekint.org/2017/01/22/leonardo-and-the-reinvention-of-anatomy/. Accessed March 14, 2022.

- Osler W. The Evolution of Modern Medicine: A Series of Lectures Delivered at Yale University on the Silliman Foundation in April 1913. Nabu Press, 2013.

- Agrawal A. Musculoskeletal etymology: What’s in a name? J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2019 Mar-Apr;10(2):387-394. Epub Feb 23, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2018.02.009.

- Online Etymology Dictionary. Etymology, origin and meaning of catecholamine. https://etymonline.com/word/catecholamine. Accessed March 14, 2022.

- Wulff HR. The language of medicine. J R Soc Med 2004;97(4):187-188. doi:10.1258/jrsm.97.4.187.

- Skinner HA. The Origin of Medical Terms (2nd Edition). Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkins Company, 1961: 25, 38-39.

- Koch-Weser S, DeJong W, Rudd RE. Medical word use in clinical encounters. Health Expectations 2009;12(4):371-382. doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00555.x.

- Young M, Norman G, Humphreys K. The Role of Medical Language in Changing Public Perceptions of Illness. PLoS One 2008; 3(12):e3875. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003875.

EVE ELLIOT is a novelist and essayist with a particular fascination for medicine and the arts. Her previously published articles have explored the deadliness of rain in Jane Austen books and the phantom pregnancies of Queen Mary I of England. She lives in Dublin, Ireland.

Leave a Reply