Benjamin Darkwa

Edmonton, Canada

Introduction

|

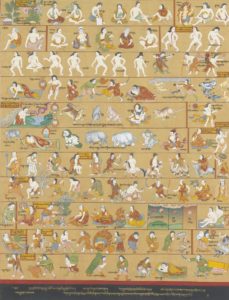

| Figure 1. Medical tangka: synopsis of the three humors. Romio Shrestha. Courtesy of the Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History, 70.3/ 5479. |

As one of the oldest medical traditions, Ayurveda has existed for about two thousand years.1 Caraka and Susruta are the most famous medical compendiums of Ayurveda. These classical texts associate diseases with the imbalance of three dosas (humors): vata (wind), kapha (phlegm), and pitta (bile).

The three dosa theory, illustrated in Figure 1, explains how each of the dosas may burden the physical and mental health of an individual.

Although the discussion of women’s health in Ayurveda is somewhat limited, Carakasamhita and Susrutasamhita cover conception, pregnancy, and the postpartum period.2,3 The Susrutasamhita discusses women’s health in the section on physiology and covers difficult labor in a section on anatomy. Diseases of the vagina and uterus are discussed in the chapter on the nine grahas (disease demons) who seize children’s and women’s bodies and cause convulsions. The tenth chapter discusses diseases of the breast.3 The Carakasamhita also has valuable information on women’s health, and especially disorders of female genitalia. It identifies twenty disorders of the vagina and uterus and contains usable suggestions for the treatment of menstrual disorders and defects of breast milk.3

These two medical treatises prescribe the management and care of pregnant women from conception through delivery to postpartum care.3 Selby3 (p. 257) argues that these prescriptions appear with expressions such as “one should give her,” “one must make her sit,” “one should implore her,” “she should drink,” and “she should eat.” Susruta also provides detailed information on what is required to attract or prevent an attack from the nine grahas.

The texts have poetic information based on color classification of gender: women and feminine are red; men and masculine are white. Selby3 believes that this classification scheme may have been associated with the color of sexual effluents, menstrual fluid and semen. Interestingly, Ayurveda associates the color red, menstrual blood, and the female body with fire, while the whitish semen of men is classified as cool. In essence, women’s menstrual blood, which is both red and fiery, meets with the coolness of the man’s semen to create an embryo.4

This classification scheme is used to explain the occurrence of certain diseases and attacks on women’s health. Ayurvedic literature likens the body of a woman to a jug: “flexibly adjusting and constantly changing.”3,5 Since the “redness” of women is associated with openness, they are also believed to be more susceptible to outside influences such as attacks by the grahas. Menstruation and childbirth are major stages where women become more open, therefore requiring isolation and insulation against all forms of pollution.6

The interpretation of the information on women’s health in Ayurveda has been inconsistent. For instance, concerning conception, Selby2 argues that the European interpretation presents slightly different information from the Sanskrit texts. The purpose of this article is neither to resolve inconsistencies nor to provide evidence to support existing arguments, but rather to discuss some of the pertinent questions concerning menstrual health in the early Indian medical tradition.

Menstruation and menstrual complications in Ayurveda

The classical texts of Susruta and Caraka provide detailed information on menstruation, menstruating women, and menstrual complications and their treatment. Kale—the appropriate age for menstruation—is believed to be between the ages of twelve and fifty.7* The Susrutasamhita uses the metaphor of a closing lotus flower to describe menstruation in women. It argues that just as a lotus flower closes when the day is over, a woman’s uterus also contracts and does not receive any seed when the period of conception is over.8 The menstrual blood collected for a month is brought by Vayu through two channels to vaginal openings.8 According to Susruta, menstrual blood is always colorless when it enters “freshly into the uterus and in part flows out via the vagina during sexual intercourse.”9 However, it turns blood-like when it is “old,” coming out as slightly black and discolored during menstruation.

The Ayurvedic literature features some prescriptions for menstruating women. Both Caraka and Susruta say that on the first three days of menstruation, the woman should remain chaste; she is not required to bathe; she is not to adorn herself; she should not sleep during the day; she is required to sleep on a low bed made of Darbha grass; and she should not take anything other than milk-pap.7 Every violation of the above principles would harm a fetus—her child would be lethargic if she sleeps during the day; blind if she uses eye ointments; suffer from eye disease if she weeps; leprous if she anoints her body with oil; mad if she speaks too much; and deaf if she hears a loud noise.7

Other menstrual complications

At the heart of the discourse on menstrual complications is the wrong timing of sexual intercourse. It is unwholesome for men or women to have sexual intercourse on the first day of menstruation. Susruta likens sexual intercourse during the “bleeding” period to an object thrown in flowing water that is swept away by the stream, so it would not lead to conception.7 It is believed that if conception takes place, the fetus dies before or during delivery. Similarly, if couples have sexual intercourse on the second day of menstruation, the child dies in the labor room. Sex on the third day would produce a child with incomplete body parts who would be short-lived.8 From a similar perspective, Jolly7 explains that if conception took place during the first three days, the child would die at birth or shortly afterwards, or become crippled. However, from the fourth day on, intercourse was considered safe.7,8

Just like all disease etiology in Ayurveda, the impairment of the three dosas causes menstruation to stop. In addition, it can make pure menstrual blood infertile.8 Pure menstrual blood and pure semen results in pregnancy. Menstrual blood is considered pure if it resembles the blood of a rabbit or a hare or has lac-color and leaves no stain in washed clothes.7 Instead of pregnancy resulting from the union of ovum and sperm, in Ayurveda, conception is a product of the mixture of male semen and pure female menstrual blood.7 During sexual intercourse, the artava of a woman flows through the agency of fire and combines with cool semen to result in pregnancy.9 According to Susruta, menstrual complications may be understood by the type of pain and color of the dosas. Some menstrual complications may be treatable, but defective menstrual blood that smells like feces, urine, or a cadaver is incurable.

Menstrual blood may be purified with a vaginal douche. Susruta also recommends a diet of fish, horse grains, sour gruel, sesame, black grain, curd, and vinegar. Defective menstrual blood can also be treated by sweating; by pastes and cloth or cotton inserted into the vagina; and by cleansing with water.7 The patient is also encouraged to drink cow’s urine and buttermilk.8

Another complication is the excessive flow of menstrual blood, whether within or outside of the usual menstrual period. This condition is referred to as Asrgdara in Sanskrit. Women with this condition may experience body aches, pain, excessive hemorrhage, fainting, the feeling of darkness, thirst, burning, and drowsiness.8 Mild symptoms may be treated with diet. In more complicated situations, known as Atiprasagena, women are treated with measures that are associated with the treatment of intrinsic hemorrhage.8

Conclusion

Some scholars have tried to interpret early Indian medicine with the lens of modern medicine, such as associating menstrual blood with the ovum. Regardless of interpretation, it seems clear that many elements of modern gynecology were initially conceived of in early Indian medicine.

Note

* However, kale can also be taken to mean the intervening period after conception when changes take place in preparation for the next menstruation.

References

- Wujastyk, Dominik. The Roots of Ayurveda: Selections from Sanskrit Medical Writings. London: Penguin Books, 2003.

- Selby, Martha Ann. “Sanskrit Gynecologies in Postmodernity: The Commoditization of Indian Medicine in Alternative Medical and New-age Discourses on Women’s Health,” in Asian Medicine and Globalization 2005, Chapter 8, 120-131.

- Selby, Martha Ann. “Narratives of Conception, Gestation, and Labour in Sanskrit Ayurvedic Texts,” Asian Medicine 2005, 1/2: 254–75.

- Tewari, PV. “Kaumarabhrtya (Obstetrics, Gynaecology, Neonatology and Paediatrics),” in BV Subbarayappa (ed.), Medicine and Life Sciences in India, IV.2, History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization. New Delhi: Centre for Studies in Civilizations 2001, Chapter 7, 219–51.

- Hanson, Anne Ellis. “The Medical Writers’ Woman,” in D Halperin, JJ Winkler, and FI Zeitlen (eds), Before Sexuality: The Construction of Erotic Experience in the Ancient Greek World. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.

- Pintchman, Tracy. The Rise of the Goddess in the Hindu Tradition. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994.

- Jolly, Julius. Indian Medicine. 1951. Translated from German by CG Kashikar, 2nd edition. Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1977.

- Sharma, Priya Vrat. Suśruta-Saṃhitā, with English Translation of Text and Ḍalhaṇa’s Commentary along with (sic) Critical Notes, 3 vols. Haridas Ayurveda Series, 9. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Visvabharati, 1999–2001.

- Das, RP. The Origin of the Life of a Human Being. Conception and the Female According to Ancient Indian Medical and Sexological Literature. Indian Medical Tradition. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas, 2003.

BENJAMIN DOMPREH DARKWA is an MA history student and a research and teaching assistant in the Department of History, Classics and Religions at the University of Alberta. Benjamin primarily researches African history and the history of medicine, environment, and culture. Specifically, he is interested in how the discourses of medicine, health, and culture have been shaped throughout history.

Leave a Reply