Ciara O’Neill

Dublin, Ireland

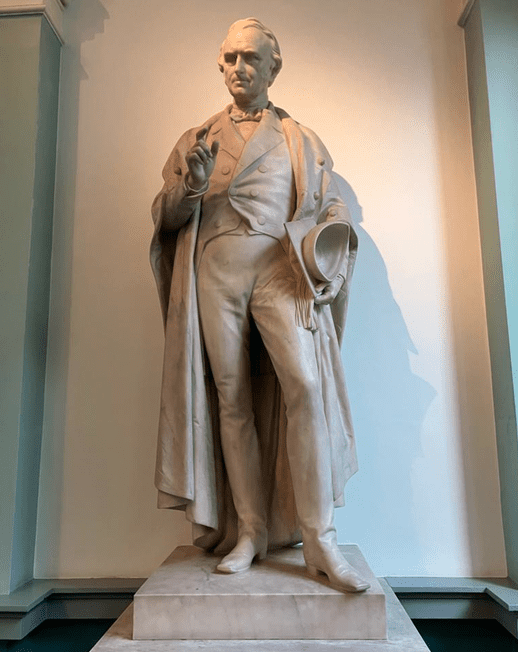

One of the most intriguing statues in the Graves Hall of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland in Dublin is that of Sir Henry Marsh (1790–1860). Alongside the three other memorials in the hall—to Robert Graves, William Stokes, and Dominic Corrigan—Marsh poses purposefully with his right arm stretched forward and index finger extended, looking every inch the earnest Victorian pioneer of Irish medicine. However, for those in the know, in real life some of those inches were missing and lovingly restored in the statuary tribute to this trailblazer of pediatrics.

The origins of this curious story lie in his young adulthood, when during a dissection in his apprenticeship to a surgeon, he cut his right index finger. Gangrene set in, and the finger had to be amputated, abbreviating his desired career as a surgeon. Changing professional direction to life as a physician, he studied medicine at Trinity College Dublin, with further time spent at the Charité Hospital in Paris.1

As Ireland was at the time entirely part of the United Kingdom, Marsh and two colleagues founded the first hospital for sick children in Great Britain and Ireland in 1821. Originally based in his own home in central Dublin, the hospital moved to a nearby street and eventually became the National Children’s Hospital in Dublin. One of the early trainees, Charles West, subsequently founded the celebrated Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital in London in 1852.2

The principles on which the hospital was founded ring true to the mission of pediatric medicine today, including free care for sick children and the importance of proper training for doctors, nurses, and caregivers. As pediatric medicine was not a dedicated specialty at the time, it is not surprising that the energetic and diligent Marsh subsequently developed a distinguished career across many other aspects of medicine. He published widely on a range of topics, was thrice elected President of the Royal College of Physicians of Ireland, and appointed Physician to Queen Victoria in Ireland in 1837.

This productivity was not at the expense of social life and conviviality, and Marsh was renowned for his engagement with dining clubs and was popular in Dublin society. When he died, his friends and colleagues collected £800 (a considerable amount at the time) to commission a memorial statue. The subscription committee was chaired by Sir Dominic Corrigan, another significant innovator in medicine, now best remembered by the eponym Corrigan’s pulse, or water-hammer pulse, as detected in aortic regurgitation.

The commission was given to the famous Irish sculptor John Foley (1818–1874), one of the leading contemporary talents in Great Britain and Ireland. As well as crafting the statues of the three other physicians in Graves Hall, other works by Foley included that of Prince Albert at the Albert Memorial in London, Michael Faraday in London, and the great Irish Liberator Daniel O’Connell in the main thoroughfare in Dublin.

Little is known of how the committee phrased the commission in terms of restoring the missing finger to the statue of Henry Marsh. However, this impulse to present an image of almost classical perfection represents a fascinating insight into the discourse of medicine and attitudes toward memorialization of those who are prominent in the profession.

The smoothing out of pathology was a notable factor in some other celebrated statues of the period, most notably that of Josiah Wedgwood, the master potter and entrepreneur from Stoke on Trent. Having suffered from chronic weakness of his right knee, attributed to smallpox, his right leg was subsequently amputated. However, the statue by Edward Davis from 1862 shows a perfectly symmetrical pair of legs.

In the twentieth century, more space has been given to portraying disability, most notably with the statue of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in his wheelchair at his memorial monument in Washington.

References

- Coakley D. Irish Masters of Irish Medicine. Dublin, Town House, 1992.

- Higgins, TT. “Centenary of Great Ormond Street.” British Medical Journal, 1(4754), (1952): 377-9.

CIARA O’NEILL is a junior doctor undertaking her paediatric training in Dublin, Ireland.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 15, Issue 1 – Winter 2023

Leave a Reply