Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

|

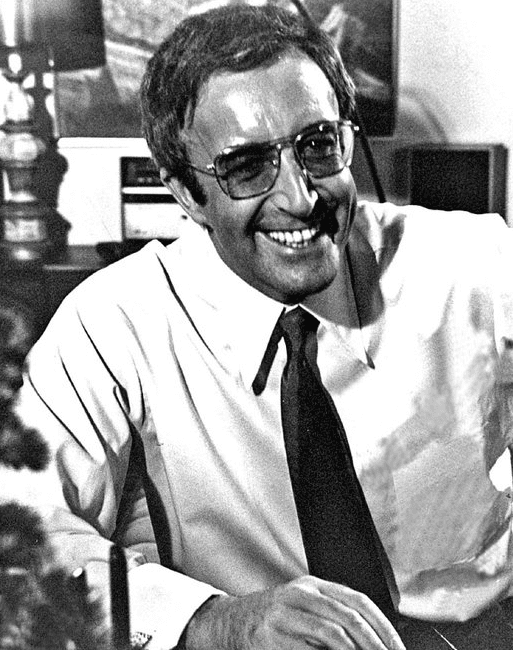

| Peter Sellers in 1971. RR Auction. Via Wikimedia. Public domain. |

“This film is dedicated to the honest, sincere MDs—whose lives are dedicated to the sacred Hippocratic oath. Will these three doctors please stand up?”

This dedication sets the tone of Where Does It Hurt? (1972). Unlike the 1971 film The Hospital, in which patients’ lives are jeopardized by inefficiency, incompetence, and insanity, this film is closer to the 1992 film Article 99, in which cost-cutting and indifference to human suffering is the theme. In Where Does It Hurt? one sees a corrupt, dishonest criminal of a hospital administrator, Albert Hopfnagel (played by Peter Sellers) and a group of doctors, all greedy, many dishonest, and some indescribably incompetent. Many nurses also take part in the administrators’ fraudulent money-taking schemes. In a brief scene, Hopfnagel looks at a photo of his hospital and says quietly, “Tomorrow the world.” Perhaps it is a coincidence that Albert Hopfnagel has the same initials as Adolf Hitler.

An out-of-work, healthy man, Mr. Hammond, comes to the hospital for a chest x-ray, since a doctor on television said that everyone who lives in polluted Los Angeles should get one. He has no insurance, but luckily for Vista Vue Hospital, he owns a house, which can be seized if he cannot pay his hospital bill. He is asked by a doctor, “Where does it hurt?” to which he responds, “It don’t.” He is talked into a battery of procedures (chest x-ray, electrocardiogram, upper gastrointestinal (GI) x-rays, lower GI x-rays, and a colonoscopy), which are all normal. He is also called by the wrong name, which becomes his name in the hospital.

Hopfnagel informs the staff doctors that there are 304 patients in the hospital, and not one of them is scheduled for surgery. He urges them to be creative, to perform elective preventive surgery, such as removing a normal prostate gland. The hospital commission wants to close Vista Vue (“view view”) Hospital, but whenever the commissioner plans a surprise inspection, his secretary secretly informs Hopfnagel of the visit—he is on Hopfnagel’s payroll.

In order to perform an appendectomy on Hammond, the lab produces a false elevated white blood cell count, and the surgeon uses that as his justification. Hammond learns about the fake blood count and the unnecessary appendectomy and informs the hospital commission. Hopfnagel tries to bribe Hammond with retroactive Blue Cross medical insurance and a hospital stay with superb food, drinks, and sex with Hopfnagel’s “fiancée.”

The jilted fiancée arranges an enormous party at the hospital. There is a band, drinking, dancing, fighting, and sex. The entire hospital staff is there (and not with the patients). Hammond calls the hospital commissioner who arrives, sees this chaos, and fires Hopfnagel. Unfortunately, Los Angeles does not have enough hospitals, so Vista Vue remains open, with the same doctors. The commissioner regrets his decision even as he announces it.

The film ends with Hopfnagel arriving by ambulance, blackmailing a doctor into planning an appendectomy for no reason, so that he can later sue the hospital. A bumbling surgeon is deliberately assigned his case, the outcome of which the viewer does not learn.

Ed Sikov, in Mr. Strangelove: A Biography of Peter Sellers, calls the film “a gleefully sour comedy” that is “raw, bitter, and misanthropic.” The film has the racial, ethnic, and homophobic slurs heard in the 1970s, mostly coming from the evil Hopfnagel.

Reference

- Ed Sikov. Mr. Strangelove: A Biography of Peter Sellers. New York: Hyperion, 2002.

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Summer 2022 | Sections | Books & Reviews

Leave a Reply