Annabelle Slingerland

Leiden, Netherlands

In the 1970s, a “patients without borders” organization made it possible for people with severe heart disease to be flown to other countries for treatment that was unavailable in their home country. It was a decade after Christiaan Barnard had pioneered heart transplantation in South Africa, and although most patients did not need heart transplants, many had plaques in their coronary arteries that, left untreated, could result in heart attack and death unless surgically treated with coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

In several European countries, the public was already aware of this new form of treatment, as exemplified by the popular Dutch song “Dokter Bernhard” in which a woman pleads with a surgeon to save her husband’s life. Surgeons who had attended conferences or trained in the Unites States had been impressed with the results of cardiac surgery. Yet they had not succeeded in implementing adequate cardiac post-operative care in their own countries. Therefore, local health and hospital systems, inundated by demand, would put patients on a waitlist. Not infrequently, they remained untreated until it was too late and they suffered subsequent heart attacks. If they survived, their physical health often deteriorated to the point that they could no longer work or care for their families.

One such patient in the Netherlands was Henk Fievet, a father of seven and an encyclopedia salesman who could no longer work or support his family after having a heart attack. His wife and children had to work in a local cafeteria. Angered by his situation and assuming that there were others like him, Fievet organized his children to go door-to-door to gather support to create an organization that could help people like him. He was helped in this endeavor by The Voice, de Stem, a local magazine in the city of Breda which published an interview with Fievet.

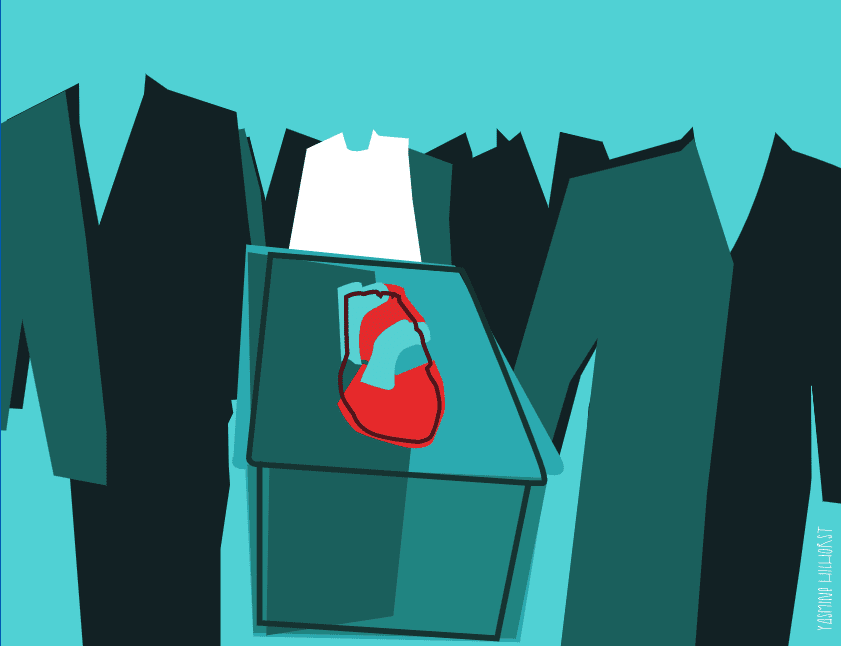

While this patient-activist organization was taking shape, some of its members, awaiting surgery, died. New waitlisted patients took their place. Believing the government could change the situation, people began to protest, carrying coffins through the streets, occupying empty hospital beds in brand new cardiac units, and storming parliament. They faulted the government for capping the number of patients who could have cardiac surgery. They learned from the surgeons themselves that some of them had lost their jobs and that operating rooms and wards remained empty. Some surgeons themselves protested by writing letters and seeking the support of hospital and government committees to elevate the status of their specialty and increase salaries to keep people on the job.

Newspapers, radio, and television also played an important role in this venture. They publicized Fievet’s work and helped him to build connections with physicians. One of these surgeons later became an advisor to the organization. The physicians made plans to build a specialty care center like those they had seen in the US, and also explored options abroad that already existed for wealthy patients with connections. One surgeon had materials sent from the US to build his own heart-lung machine, while another developed mobile heart-lung machines and training courses for use in different hospitals.

With these efforts highlighting the demand for services, Fievet successfully liaised with government officials, insurance bodies, companies that had lost employees, funders who believed in the American Dream, and a myriad of hospital professionals. By June 1976, he threatened to take the government to court if they would not support the group’s cause. Finally, a brand-new Boeing 747 took off from Schiphol airport with seven people who were high-risk cardiac patients and family breadwinners. Their destination was the famous Texas Heart Institute (THI) of Dr. Denton Cooley.

The idea had been simple. Fievet copied what individual patients with their own resources and connections had done before: fly to the US for surgery, return home, and resume work. Fievet had become incredibly knowledgeable and adept at making connections. He had now, nearly seven years into his cause, found a clause in the law saying that any patient who was unable to receive appropriate care within three months of diagnosis was entitled to receive paid care anywhere in the world.

Aware of the slow nature of bureaucracy, businesspeople who supported his efforts began to allow pre-payments for services. A nurse who had trained in the US and now worked for Royal Dutch Airlines’ medical services was contacted. Fievet asked cardiologists to phone their patients and invite them on this flight to the US. A surgeon in the US would accompany the flight, and the surgeon’s wife, also a nurse, collected all necessary medical information, including angiograms, to be discussed with Dr. Cooley.

More patients made trips to the US every two weeks. Fievet and his organization kept up their campaign for appropriate care, and airlifts were also added to London and Geneva. Meanwhile, Fievet died after a series of heart attacks in the spring of 1977. At his funeral, another heart patient was appointed to continue his legacy. Medical airlifts continued, and the UK started centers where surgeons could operate on patients from abroad.

By the 1980s, new techniques to treat coronary artery disease led to less demand for open heart surgery. The centers evolved into integrated units in which cardiologists and thoracic surgeons worked out whether percutaneous coronary angiography (PTCA) or CABG would best be applied. By the mid-eighties the airlifts had wound down, but the nineties saw a resurgence. The story of “patients without borders” reminds us that patients, by becoming aware and active, can help to direct their own fate and support important causes for themselves and others.

Author’s Note

I am grateful to the many health professionals, policy makers, patients, archivists, journalists, technicians, and family members in the US, the UK, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and other European countries who have contributed to my research and writing on this topic.

ANNABELLE SLINGERLAND, MD, DSc, MPH, MScHSR received her medical degree from Amsterdam University and Amsterdam University Medical Center and her degrees in Public Health, Health Services Research, and Genetics from the Erasmus University in Rotterdam. She has authored numerous papers in high impact journals and in Hektoen International on diabetes, famous hospitals, and other aspects of medical history.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 4 – Fall 2022

Leave a Reply