Elizabeth Colledge

Jacksonville, Florida, United States

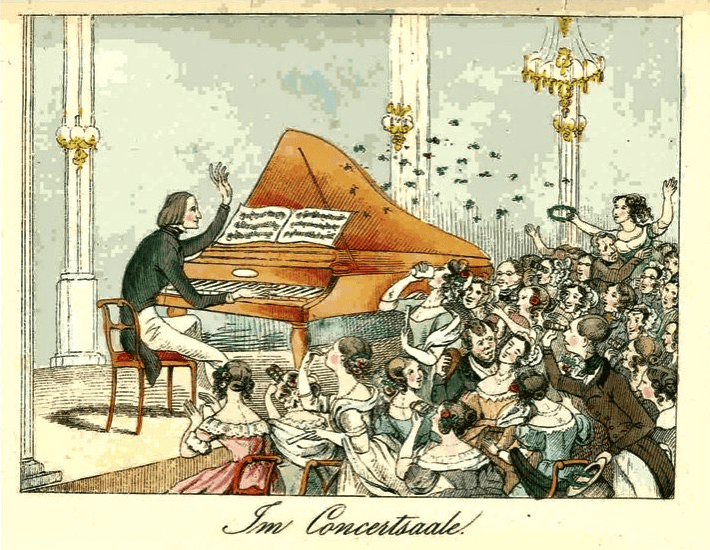

Much has been written about the hysteria accompanying Beatlemania, and before that, the frenzies generated by Elvis, Sinatra, and similar artists, primarily musicians. But before the Beatles, before Elvis, before Frank, there was Franz Liszt, whose 1844 concert in Berlin shocked the musical world and generated the term and medical condition of “Lisztomania.”

It did not hurt that Liszt was strikingly handsome, that he strode out onto the stage, seated himself dramatically, tossed his thick mane of hair, and swayed his body as he played. The audience could hardly stand it. Crowds of screaming women were thrilled by his long locks, Roman profile, and breathtaking body language. By 1844, Liszt fever, or “Lisztomania,” a term coined by the poet Heinrich Heine in his reviews of Liszt’s performances, had flooded Europe.

His fans often rushed the stage or passed out in their seats. Like the groupies of Tom Jones, they tossed underwear and flowers. They fought for his handkerchiefs, the silk gloves from his enormous hands, even the discarded butts of his cigars. Cameo portraits of Liszt were a popular item of jewelry, as were glass brooches containing a lock of his hair or the aforementioned cigar butts. Even the dregs of his coffee were preserved in vials as if they were holy water. To keep up with the demand for his hair, Liszt purchased a dog, which did not seem to bother his fans.

The pianos Liszt played were not as strongly constructed as those of today, and Liszt played the instruments so aggressively that he often broke strings or damaged a piano to the point of cracking the case. Eventually he placed an additional instrument on stage as a backup, and once had three pianos on stage. The audiences became disappointed if he did not break any strings, which they fought over and turned into bracelets.

Liszt invented the modern recital. He first used the term to advertise two 1840 concerts in London as “Liszt’s Pianoforte Recitals.” Prior to that, he referred to his performances as “musical soliloquys.” The first solo pianist to play entire programs from memory, he drew upon the full range of the keyboard repertory from Bach to Chopin in addition to his own compositions. Sometimes he performed before as many as three thousand people, placing the piano at right angles to the platform so the audience could see his profile and keeping the lid open to amplify the sound. His compositions featured revolutionary keyboard techniques and musical ideas that are utilized by pianists to this day.

Born in 1811, Liszt began studying piano at seven and performed his first solo concert at the age of nine in Bratislava. From 1839 to 1847 he crisscrossed Europe as a concert pianist, foreshadowing today’s worldwide tours. Unlike most modern artists, Liszt was responsible for the principal aspects of the tours, from venues to advertising. When he added conducting to his playbook, he revolutionized that art as well. According to the concert pianist Stephen Hough, “Before Liszt, a conductor was someone who just facilitated the performance, who would keep people together or beat the time, indicate the entries … After Liszt, that was no longer the case; a conductor was someone who shaped the music in an intense musical way, who played the orchestra as an instrument.”

Heinrich Heine first used the term Lisztomania in a feuilleton reviewing the 1844 musical season: “The electric action of a demonic nature on a closely pressed multitude, the contagious power of the ecstasy, and perhaps a magnetism in music itself, which is a spiritual malady which vibrates in most of us—all these phenomena never struck me so significantly or so painfully as in this concert of Liszt.” In subsequent articles, Heine further elaborated upon the phenomenon.

But whereas we think of Beatlemania or Elvis as a craze or temporary mania, Lisztomania, or Liszt fever, implied a more serious medical condition, one dangerous enough to elicit recommendations from medical professionals for cures or immunization. Could it be a form of widespread epilepsy? Was it mass hysteria? Did it rise from a germ inherent in concert halls? Some sort of musical aphrodisiac? Theories included the results of oxygen deprivation in a crowded hall or the neurological effects of Liszt’s rapid tempos on the brains of audience members. Men were not immune from his extraordinary charisma. Hans Christian Andersen confessed in his diary, “When Liszt entered the saloon, it was as if an electric shock passed through it … as if a ray of sunlight passed over every face.” Yuri Arnold, a contemporary music critic, also enthused over Liszt’s performance: “As soon as I reached home, I pulled off my coat, flung myself on the sofa, and wept the bitterest, sweetest tears.”

Suggested remedies ranged from leeching to bloodletting, from consulting mystics to taking laudanum. All to no avail. Lisztomania finally abated with the artist’s retirement. But variants continue to emerge, though few at the same fever pitch as the original.

References

- Brislan, Patrick, Heresies of Music: An A-Z Diagnostic Guide (Australia: Vivid Publishing, 2016), 127–135.

- Burton-Hill, Clemency, “Forget the Beatles – Liszt was music’s first ‘superstar,’” BBC Culture, August 17, 2016, https://bbc.com/culture/article/20160817-franz-liszt-the-worlds-first-musical-superstar.

- Keller, Johanna, “In Search of a Liszt to Be Loved,” The New York Times, January 14, 2001, archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20110420024121/http:/www.nytimes.com/2001/01/14/arts/14KELL.html?pagewanted=all.

- “Lisztomania,” Wikipedia, last modified December 14, 2021, 02:28 UTC, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lisztomania.

- McGarvey, Kathleen, “Longing for Liszt,” Rochester Review 79, no. 4 (March–April 2017): 16–17, https://rochester.edu/pr/Review/V79N4/0307_liszt.html.

- New World Encyclopedia contributors and Wikipedia contributors, “Franz Liszt,” New World Encyclopedia, accessed July 22, 2022, https://newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Franz_Liszt.

- NPR Staff, “How Franz Liszt Became The World’s First Rock Star,” NPR, October 22, 2011, https://npr.org/2011/10/22/141617637/how-franz-liszt-became-the-worlds-first-rock-star.

- Oliver, Mark, “10 Crazy Facts About Lisztomania,” Listverse, December 13, 2017, https://listverse.com/2017/12/13/10-crazy-facts-about-lisztomania/

ELIZABETH L. COLLEDGE, PHD, holds a B.A. in English from Wellesley College (1974) and a Ph.D. from the University of Florida (1991) with the dissertation Wordsworth’s Challenges to Gender-Based Hierarchies. She has taught high school English and worked as a freelance editor for both individuals and non-profit institutions. In addition to writing poetry and short fiction, she has served as an assistant editor for Narrative and is currently an editor for Hektoen International.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 4 – Fall 2022

Leave a Reply