JMS Pearce

Hull, England

William Blake (1757–1827) (Fig 1) was and still is an enigma. He was born on November 28, 1757, one of seven children to James, a hosier, and Catherine Wright Blake at 28 Broad Street in London.1 He once remarked: “Thank God I never was sent to school / To be Flogd into following the Style of a Fool.” He was by trade an engraver but when not scraping together a meager living, he was one of the most original, fertile, and mystically creative geniuses of any age.2 The art critic Jonathan Jones regarded him as, by far, the greatest artist Britain has ever produced. This brief synopsis concentrates more on his anti-authoritarian ideology than on his art.3

He was born into a household of Dissenters. As a boy, he studied art at a drawing academy and served a long apprenticeship with the engraver James Basire before entering the Royal Academy Schools.3 In 1782, he married Catherine Boucher in her family’s church, Saint Mary’s, Battersea. Illiterate, she signed the marriage register with an X. He taught her to read, write, and assist him in his printmaking. Much of their lives was spent in poverty and they had no children. Except for a brief period in Felpham, he spent his life in London.

A profound scholar, his philosophy was influenced by Emmanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772), the Christian theologian, scientist, philosopher, and mystic best known for his book on the afterlife, Heaven and Hell, though Blake later refuted some of Swedenborg’s conceits. Other important influences were Paracelsus, the poet Milton, and the mystic Lutheran, Jacob Boehme (1575–1624).

Blake produced many beautifully illuminated works of poetry, revered after his death, most famously the Songs of Innocence and of Experience, Jerusalem, and Milton.4 But during his lifetime they secured little praise.

It was not until Alexander Gilchrist’s painstaking biography in 1863 (with its subtitle Pictor Ignotus—The Unknown Painter) (Fig 2), published forty years after Blake’s death, that his reputation was finally established,5 promoting a huge literature of biographical,6,7 artistic, religious, and philosophical comment.2,8

Blake’s was a time of great social and political upheaval: the rapid growth of industrialization, didactic science, and new styles of art. The rich were very rich and lived in a different world from the cruelly exploited poor. Blake’s work explores the tensions between human passions, deprivations, and the repressive nature of social and political conventions, which appalled him. He saw himself as a national prophet who strived to change both the social order and the minds of men by promoting his unique brand of spiritual, imaginative life. He had a sense of the spiritually transcendent, evoking a heightened sense of the mystical and sublime.

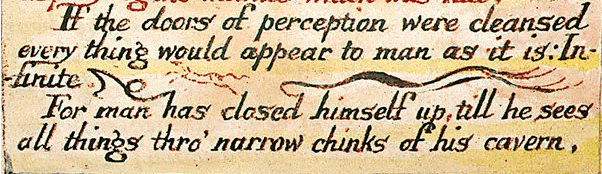

The Aristotelian “philosophy of the five senses” espoused by scientists and philosophers argued that both the world and the mind operated by fixed laws, which failed to include imagination, creativity, or a spiritual life. Blake vehemently decried this materialistic view, typified by Bacon, Locke, and Newton. His Newton (1795) demonstrates his opposition to the “single-vision” of science and his quest for harmonious, free spirituality. In Jerusalem, In Deadly Fear, he epitomizes his philosophy:

I see the Four-fold Man, The Humanity in deadly sleep

And its fallen Emanation, The Spectre and its cruel Shadow.

I see the Past, Present and Future existing all at once

Before me. O Divine Spirit, sustain me on thy wings,

That I may awake Albion from his long and cold repose;

For Bacon and Newton, sheathed in dismal steel, their terrors hang

Like iron scourges over Albion: Reasonings like vast Serpents

Infold around my limbs, bruising my minute articulations.

I turn my eyes to the Schools and Universities of Europe

And there behold the Loom of Locke, whose Woof rages dire,

Washed by the Water-wheels of Newton: black the cloth

In heavy wreathes folds over every Nation: cruel Works

Of many Wheels I view, wheel without wheel, with cogs tyrannic

Moving by compulsion each other, not as those in Eden, which,

Wheel within Wheel, in freedom revolve in harmony and peace.

In 1800, Blake left London to live in Felpham, Sussex. He was arrested there, having ejected from his garden a soldier, who claimed Blake had said “Damn the King” and other seditious words. Blake stood trial but was acquitted.

He then started work on Milton, whom he regarded as a true poet, but one misled by Puritanical dogma. The preface includes the poem beginning “And did those feet in ancient time,” which founded the stirring but rebellious anthem Jerusalem that protested: “And was Jerusalem builded here, Among these dark Satanic Mills?”

Songs of Innocence and of Experience

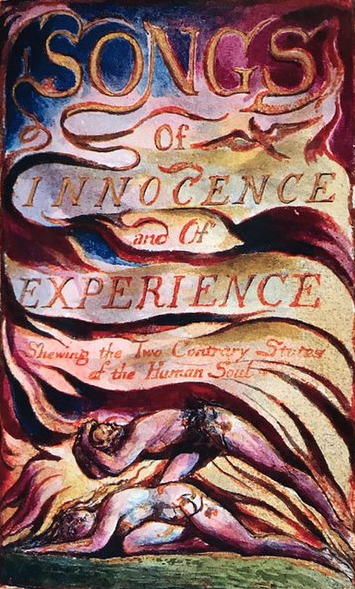

In Songs of Innocence and of Experience, (Fig 3) perhaps his best-known collection of poems, he exposes, as the subtitle indicates, two contrary states of the human soul.

The superficially benign and gentle Songs of Innocence contrast sharply with darker, corrupt sins of adulthood in the Songs of Experience. At first glance, his poems seem childlike with simple rhymes often picturing children, animals, and flowers. The tiger, a contemporary symbol of the French Revolution, surfaces in his famous but strident, political poem “Tyger tyger burning bright…” In it, he asks how could one God have created both the Tyger of cruelty and the Jesuitical Lamb of love and imagination: “Did he who made the Lamb make thee?”

At a deeper level, the songs hint strongly of satirical, vehement distaste for exploitation, authority, and the political manacles2,9 of his day:

In every cry of every man,

In every infant’s cry of fear,

In every voice, in every ban,

The mind-forged manacles I hear

This protest echoes in George Orwell’s 1984.10 Songs of Innocence and of Experience combines both his remarkably vivid art from etched copperplates, intaglio engraving, and painting3,8 with his satirically critical poems influenced by the rhymes and ballads of his childhood.1 At the time of his death, however, fewer than twenty copies had been sold in thirty years.

Prophetic Books

His several Prophetic Books portray his complicated personal visions and mythology, in which he formulated his spiritual and political ideas into a prophecy for a better world. His brother Robert’s death, aged twenty, deeply affected Blake, who saw his brother’s soul ascend heavenward clapping its hands for joy. His eclectic, mysterious stories were populated both by characters from the scriptures and those of his own numinous, imaginative invention—far beyond the awareness or imagination of ordinary people. Some such expressions were of beguiling simplicity:

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower,

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour.

His tales tell of struggles between enlightenment and free love with man-imposed manacles of freedom, education, and morality. Many of his images hark back to Biblical, Greek, and Norse mythology. When he died, his Prophetic Books containing his ideas disappeared almost without trace. The fanciful imagery and notions, so real, joyous, and vivid to him, are often difficult to understand. But ultimately, redemption is the liberation or freedom of man by his own efforts—the reconciliation of his Albion and Jerusalem.

The Four Zoas

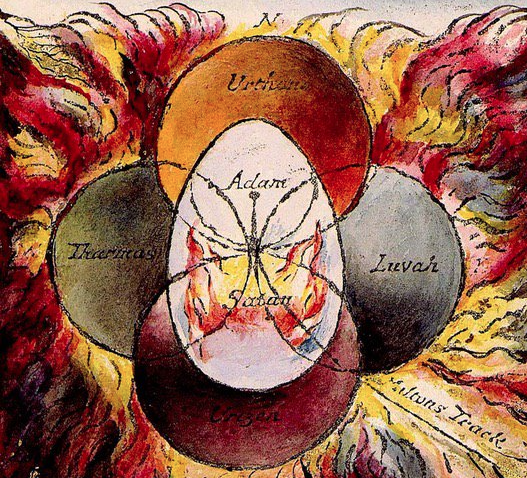

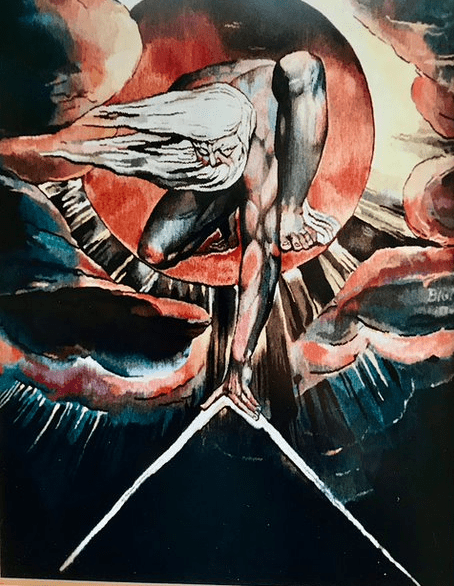

Urizen is one of The Four Zoas: The Torments of Love & Jealousy in The Death and Judgment of Albion the Ancient Man that result from the spiritual decline, the fallen Albion, emblem of the primordial spiritual Britain (Fig 4). Albion is divided into four Zoas, who have varying complex roles in Blake’s stories (Fig 5):

Tharmas: represents sensation and instinct

Urizen: a symbol of tyrannical reason and willful convention

Luvah: symbol of love and passion whose fallen form is Orc the rebel, opposed to Urizen

Urthona: the imagination, whose fallen form is Los, father of Orc.

Jerusalem was Blake’s final epic poem (c. 1818), a tale that explores the fall of Albion, who is Blake’s vision of Man through Jesus, and his ultimate redemption. Albion rejects Jerusalem, his female counterpart or Emanation. The labors of the prophet Los spare him from further spiritual decline. For he is ultimately reunited with Jerusalem, the divinity within him, and only then achieves spiritual freedom.

Religion

Blake was a radical luminary, much moved by the ideals and damages of the French and American Revolutions. His passionate invective repeatedly denounced poverty, child labor, political authority, industrialization, and the abuses of “every black’ning church.” A devout Christian, he believed in the messages of the Bible, but perhaps not in a traditional, celestial deity, for he remarked that all deities reside in the human breast as the power of imagination. He poured contempt on didactic, organized religion, which he saw as betraying the true Christian faith. Proverbs of Hell rebels against a Church viewed as oppressive, yet powerless to remedy the decadent prisons and brothels. He challenges the commonplace values of good and evil:

Prisons are built with stones of Law,

Brothels with bricks of Religion.

The pride of the peacock is the glory of God.

The lust of the goat is the bounty of God.

The wrath of the lion is the wisdom of God.

The nakedness of woman is the work of God.

Visions

Whereas contemporary artists Turner and John Constable painted rural landscapes and seascapes, Blake painted the spiritual landscapes of his fervid imagination. He frequently experienced ecstatic and joyful visions and therefore was often thought of as mad.11 His wife Catherine once complained: “I have very little of Mr. Blake’s company. He is always in Paradise.”

Revealingly, he wrote: “I am more famed in Heaven for my works than I could well conceive. In my Brain are studies & Chambers filled with books & pictures of old, which I wrote & painted in ages of Eternity before my mortal life; & those works are the delight & Study of Archangels.”

The Poet Laureate Robert Southey dismissed him as “a man of great, but undoubtedly insane genius.” Gilchrist carefully defined the “special faculty” of his imagination, and vindicated the profound spiritual sanity of the “gentle yet fiery-hearted mystic… His playthings were sun, moon, and stars, the heavens and the earth.”12 Peter Ackroyd commented that he might have been “some star-child, or changeling, who withdrew into himself and into his own myth because he could not deal directly or painlessly even with the human beings closest to him.”

The visionary Blake was also down-to-earth. He strived to make his writings understandable, to illustrate and remedy commonplace daily events and lives at a time of social unrest. His implacable purpose in life was redemption: “To open the Eternal Worlds, to open the immortal Eyes of man …” He also realized that some of his conceits were, of necessity, obscure.8 Bronowski shrewdly observed that when we have learnt Blake’s language, we have still to judge what he said with it.

Blake was undoubtedly a vexing, confrontational character, who received much criticism. His strange isolation and exultant, supernatural visions caused many in his own time to deride him. His unique poetry and visual art were thus ignored or traduced. He understood the society that had unkindly rejected him, yet he showed compassion for the suffering and injustice he daily witnessed in London’s streets.5

——

It is impossible to condense adequately the vagaries of Blake’s imagery, transcendent beliefs, and social remedies. He advocated gender equality and sexual freedom: the pleasures of sexual union he celebrated as an entrance to a spiritual state. He opposed all repressive authority, marriage laws, and slavery.

In Jerusalem, he foresaw redemption based on forgiveness and self-sacrifice. He was solitary rather than arrogant in beliefs bred of his extraordinary prophetic phantasms and imagination. Apart from Swedenborg, in these he stands almost alone. Not surprisingly, in his lifetime, his works were doomed to obscurity.13

His many biographers remain perplexed by the strange, mystical forms of his characters, specters, and pictures. Modern scientists and physicians would disparage his drastic opposition to the single vision of scientific materialism. But it appears this opposition was based more on the danger he perceived of science’s rejection of a spiritual world than a denial of a coexisting science. Ordinary human perceptions are pale imitations of his numinous senses, the reality of his private eternity. His legacy perhaps was anticipated by the great Bard:

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on…

Blake influenced the artist Samuel Palmer and the Pre-Raphaelites Morris, Rossetti, and Swinburne; he was admired by WB Yeats, Allen Ginsberg, Bob Dylan, and Aldous Huxley. Many other-worldly notions in Philip Pullman’s trilogy His Dark Materials echo Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. His legacy lies in his selfless, down-to-earth devotion to suffering humanity and his attempts to vanquish injustice, especially in what he saw as the “Thou shall not” manacles of Church and State.

After several attacks of abdominal pains, shivering, jaundice, and probable cholangitis (attributed by Keynes to “gallstones and inflammation of the gallbladder”), he died in Fountain Court, the Strand. His friend George Richmond wrote: “He died on Sunday night [August 12 1827] at 6 o’clock in a most glorious manner… Just before he died: His Countenance became fair—His eyes brighten’d and He burst out in Singing of the things he Saw in Heaven.”

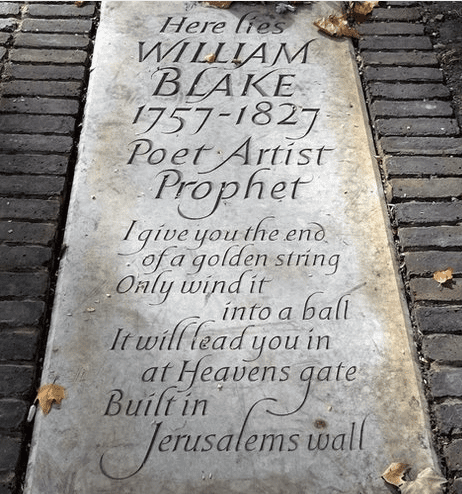

He was buried next to Catherine at Bunhill Fields, Finsbury, notably a cemetery for non-conformists. (Fig 6)

References

- William Blake. Poetry Foundation. http://www.blakearchive.org/blake.

- Bentley G.E. The Stranger from Paradise: A Biography of William Blake. New Haven and London: Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2001.

- Keynes G. William Blake: Poet Printer Prophet. London. Methuen 1965.

- Keynes, Geoffrey. The Writings of William Blake: Edited in Three Volumes. London: Nonesuch Press, 1925.

- Ackroyd Peter, Blake. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1995.

- Erdman David V., ed. The Complete Poetry & Prose of William Blake, with a commentary by Harold Bloom. New York: Anchor/Doubleday, 1982.

- Gillham D.G. William Blake. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1973. 40-54.

- Keynes Geoffrey, editor 2nd ed. Blake Complete Writings. Oxford University Press 1969.

- Bronowski Jacob (1972). William Blake and the Age of Revolution. Routledge & K. Paul.

- Michael Ferber, The Social Vision of William Blake. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1985.

- Andrew M. Cooper. Blake and Madness: The World Turned Inside Out. Johns Hopkins University Press 1990; 57:585-642.

- Gilchrist Alexander. Life of William Blake (1863).

- Delphi Complete Works of William Blake (Illustrated) Delphi Classics; 2nd edition (14 Sept 2012).

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of science and medicine.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 4 – Fall 2022

Leave a Reply